In between previews of awards fare and highlights from the year’s festival circuit, each edition of the Ghent Film Festival delivers a focus on one nation. In recent years, Nordic and American independent cinema, Britain, France, Hungary, and Italy have all had the treatment. This year, the festival has turned to Spain. Alongside a main strand of contemporary Spanish cinema, comes a selection of older ‘Classics’, including a significant retrospective of Augustí Villaronga (°1953). The programme comprises a bold starting point for post-Franco Spanish cinema, with a combination of well known names and other films that showcase the rich genre tradition in the country.

Patrick Duynslaegher, former artistic director of the festival and one of Belgium’s most prominent film critics, continues to programme this strand: “The area that interests me at this point in my life is film history.” The concept for this year’s selection is taboo breakers. These mostly take the form of late-night genre movies, although recognisable names include Jamón Jamón (Bigas Luna, 1992) and El espíritu de la colmena (Víctor Erice, 1973). The strand largely covers the period of creative explosion coinciding with the end of the dictatorship in 1975.

Censorship had emphasised Catholic values and apolitical sentiment (not dissimilar to the US Hays Code, without the specific commandments), and it didn’t immediately end with Franco, which makes the decade of the 70s a dam of expression fit to burst, and the choices here come from a large range of directors and prestige. “The three titans of Spanish cinema, José Luis Berlanga and Juan Antonio Bardem along with Luis Buñuel, would have been an obvious route,” says Duynslaegher. That the strand covers the 1970s onwards is a significant curatorial detail. The choice to minimise the focus of this historical strand groups these films together as a movement of sorts. By the time censorship ended in 1977, a transgressive strain in Spanish film had obtained a firm foothold.

But it is difficult to build a holistic view of a nation from an outsider’s perspective on its film history and tradition. “For political reasons, Spanish film history is fragmented: the civil war, the Franco dictatorship, and then afterwards it was officially a democracy but took some time to adjust completely. These themes dominate Spanish cinema, even now, they come up either directly or indirectly.” In Viridiana (Buñuel, 1961), the only pre-1970 film included, these themes are unmistakably direct. The title character (Silvia Pinal) plays a woman who, moments from taking her monastic vows, is summoned to meet her necrophilic uncle. From there, her attempts at virtue are corrupted by both the rich and poor. Buñuel, working in his homeland for the first time since Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread, 1933), defied censorship by directing with a subtle polish, under which lies aggression of fascist mob mentality wrapped around Freudian sexual inadequacy.

If Viridiana is a shit stained message in a bottle, the films that chronologically follow it in the strand are something of a collecting of breath in the years that followed. “[Even with] directors who started a certain time after Franco, [the mark of the dictatorship] still comes through.” Almódovar is perhaps so popular, in part, because his films so vibrantly show the reactive quality of this period.

The selection does not offer many hints as to the pre-Franco cinema. The state repression did not allow for a New Wave at the same time that Italy, Germany, or France experienced their shifts into modernist filmmaking. Perhaps only Buñuel rode the crest of the international film movements. For Duynslaegher, “Buñuel is a paradox—the greatest Spanish director who didn’t shoot many films in Spain. His early films are too avant-garde, leaving Viridiana. If we chose his greatest, it would have been Tristana (1970)? Also about repressed society, but Viridiana is much more provocative, and was at the time.” It provides a context for these proto-punk films but doesn’t give much of an impression of the pre-Franco cinema. However, Viridiana sets the table for many of the other films in the strand in surprising ways.

A recurrent setting of many of these films is the old ornate house, its isolation providing an opportunity for psychological introspection. In between the melodramatic plot twists and explosions of sex and violence, is a still atmosphere that sends these characters into a liminal zone where surface level riches of the house are evidently a cover up for decaying facades of wealth. In the real world, the country was economically ravaged while the world began to get smaller. From 1939, when the Civil War ended in Nationalist victory, Spain existed under autarky, a state of total isolation and self-sufficiency from the outside world. This lasted for 20 years, until the country found itself in near bankruptcy. Opus Dei and the United States pressured the implementation of a free market economy in 1959, which slowly lead to the kind of outside cultural influence that eventually caused the regime’s collapse after Franco’s death in 1975. Some of cinema’s best remembered images of Spain come from this period, when international productions such as Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns exploited its versatile landscape for their locations, while the short-lived Samuel Bronston Productions pumped out El Cid (Anthony Mann, 1961) among other epics, to cash in on the inflated scale of mainstream American films in this era. That the films repeat this isolated mansion setting does make their selection here into an even clearer metaphor for the headspace of the nation after Franco.

Geraldine Chaplin became a popular figure in Spanish cinema around this time, notably for her collaboration with Carlos Saura, which some have compared to Godard and Anna Karina. Chaplin made an appearance in Ghent to introduce Ana y los lobos (Saura, 1973). Talking about her protest at Cannes 1968, pulling the curtains back shut on another of her films with Suara, Peppermint Frappé (1967), she is keen to highlight the rebelliousness in her own filmmaking that comes through the strand. Saura—generally regarded as the second great Spanish director after Buñuel, and the influence is plain to see—somehow avoided censorship on Ana y los lobos, a brilliant warning shot about male desire. Hired as a nanny in a mountainside chateau, Ana (Chaplin) fends off the desires of three brothers, building to delicious crescendos, like when she makes brother Juan read aloud the explicit telegram he’s anonymously sent her: “oh that’s funny, it isn’t signed.” A shot of brother José desperately fondling at Ana while she laughs, oblivious to his non-fatherly advance, is chilling, and Saura is sly to pan across the scene, so this takes up just one part of the mise-en-scene.

Fernando Fernán Gómez, the strand’s representative Daddy between his role here and in El espíritu de la colmena, represents a spiritual order and piety that Ana disrupts. He kneels before God and refuses meals while inhabiting a nearby cave. Military uniforms are José’s kink, while Juan’s aggressive sexuality blatantly disrupts the family structure. The metaphor for Franco’s Spain is clear. Still, this obvious allegorical tale is so witty, full-blooded and savage when it hits its targets, especially in the still harrowing last scene, that it works. No spoilers, but it turns out the real wolves were the men all along.

Despite Saura’s acclaim, Duynslaegher’s strand leans away from traditional categories of taste. The choice of horror film ¿Quién puede matar a un niño? (Who Can Kill a Child?, Narciso Ibáñez Serrador, 1976) might seem incongruous with what we think of as a festival film, but it offers rumination on isolation and generational angst, set on an island where empty walls house some kind of traumatic history that goes unspoken. While signs of civil war in Asia make Spain’s fragile statehood an early cause of concern for the central holidaymaking couple—“you know, there was a civil war here not so long ago”— it is the next generation who get their own back here, rejecting the sins of the father, killing every adult on the island. Narciso Ibáñez Serrador builds the atmosphere by exoticising Spanish ‘islanders’, in a piquant portrait of British arrogance abroad. The holidaying couple’s refusal to understand other languages (or even try) gets poked fun at, the pair of stiff-upper-lippers suffering for their complacent boomer mentality. In 2019 its political message of generational unrest can be interpreted as a precursor to Greta Thunberg’s rise. “Horror is so important in Spain now that I needed to include one,” Duynslaegher tells me about its inclusion. But the threads of horror are visible across the strand.

One of the great films to confront the notion of genre directly is El espíritu de la colmena, often cited as the greatest Spanish film ever made. Set just at the end of the Spanish civil war, it follows the day-to-day life of two children, six-year-old Ana and her older sister, rendering their inner life with simplicity and grace. The imagined spectre of Frankenstein encroaches on the film after the sisters see a dusty print of James Whale’s eponymous classic. Erice articulates imagination not through exuberant production design but by using empty spaces and soft lighting to suggest an absence that sets the imagination ablaze. It’s the kind of ‘canon’ film that many would cop to not having seen, but its accessibility is reflected in the packed auditorium that turns out for Erice.

I wonder what needs to be done for sustainability around a strand like this. How much context do viewers need before they can take part? Do they need a certain familiarity with Spanish cinema, or to watch these films in tandem with the contemporary Spanish strand? Duynslaegher insists he isn’t trying to win anyone over who isn’t already intrigued: “It was essential to get the readers of magazines here, to speak to an audience that’s already there.” Where an enormous festival like Cannes will have a gestural classics strand to preview some of the next year’s 4K releases, the Ghent approach has some kind of exploratory purpose. Duynslaegher admits the influence of Bologna’s repertory extravaganza Il Cinema Ritrovato, but although he is realistic about the size of his festival, the economics of programming don’t seem to be an issue, “I had carte blanche.” That claim must come with caveats. As explained in numerous introductory lectures before the screenings, the festival has a mission towards the “education of the audience”, as required by the funding body. There is some imperative therefore to provide an introduction to the nation’s cinema rather than to simply launch viewers into Spanish deep cuts. Here too, the strand’s complementary nature to the contemporary Spanish strand is revealed. It behoves the strand to offer an accessible route through its films.

Mentioning my suspicions that some films were programmed for their seeming guarantee of a packed audience, I’m met with a shake of the head by Duynslaegher: “[Penelope Cruz/Javier Bardem erotic melodrama] Jamón Jamón is less provocative and taboo breaking than [Bigas Luna’s] earlier work, but was the only one available.” Despite his commitment to subversion, it’s good to have such a known quantity like here, to ground the strand, give an entry point for the uninitiated. “The more films [Luna] made, the softer he became. Almodóvar is the same, but as he grows old he is interesting, more introspective, growing from an outsider to an explorer into the psyche of people; he is a new Bergman. His earlier films [before Matador] are not what you would call well made. But by now he is a master of mise-en-scene, a master of contemporary cinema.”

But what isn’t here? The absence of a director who isn’t male and white makes one question how alternative this cinematic narrative is, and if genre is really a holistic lens to frame Spanish cinema. “In the history of Spanish cinema, there are so few female filmmakers—one of the effects of fascism is that women are not able to make film, so there is not a tradition of women directors. I had one woman in my wish list—our original wishlist of around 20 came down to 9—, Pilar Miro, whose film Beltenebros (Prince of Shadows, 1992) won a prize at Berlin. But we couldn’t get the film in time.” While directors like Isabel Coixet or Ana Mariscal are out there, their inclusion would have changed the programme’s scope either in subject or era. The same goes for the absence of a figure like Pere Portabella, whose rejection of Franco-reactionary social-realist cinema associated him with the ‘Barcelona School’ of cinema, and put him in opposition to figures like Erice and Suara. But clearly, choosing the films isn’t as simple as making a representative list. “Half of what’s in here was my second choice, if that doesn’t sound too negative! There were so many prints we couldn’t find. That wouldn’t happen in a French retrospective. They have a better heritage. There are no big efforts in Spain to keep the memories of film, it seems.” This isn’t entirely true. The Filmoteca Española is constantly expanding its collection of over 35,000 titles from Spain and abroad, and offers a rich selection of the nation’s cinema in retrospectives at home. Perhaps the biggest issue is in the availability of Dutch or English subtitles, which may have ruled out titles from the Filmoteca.

One of Duynslaegher’s finds offers a rare 35mm screening at Ghent. Eloy de la Iglesia’s El Diputado (1978) tackles the relationship between a closeted congressman and his rent boy, who has been hired by fascists to bring him down. Filled with images of roman statues and paintings of revolutionary Spain, it raises questions of freedom, democracy, and the necessity of hedonism within that, as ideology is eroded from all sides. With his election as a Deputy in the country’s first democratic elections (during La Transición), the congressman, Roberto, is turning from a subversive into a part of the establishment, and yet is still forced to hide parts of himself—the parts that made him a socialist. His hidden life leads to his corruption, how can he be a socialist if still a wealthy guy, paying for a secret flat on the party dollar? El Diputado follows a lucid literary structure, with flashbacks embedded in narration, that utilises its few locations to expand psychological space, like Fassbinder, to whom Iglesia has been compared. Though there is no real aesthetic similarity here (I didn’t spot a single woman staring into a mirror for the 2hr run time), the frankness with which Iglesia deals with keeping sexual frustration in the subterranean plain does evoke the German master, like in the lurid introduction to the homosexual storyline through a doctor’s mention of abject boils on a patient’s penis, which grabs the attention of Roberto.

Other times, socialist beatings by punks are juxtaposed with coke fuelled orgy scenes, to put a point on the uncomfortable power dynamics. Roberto believes in the righteousness of a subversive act as sanctifying. When he tries to entertain his boyfriend with music, he only has The Internationale in the tape deck. If El Diputado has dated—when he smokes the reefer for the first time his eyes widen as though in a snobs versus slobs college comedy—it remains relevant in how it depicts a comfortable life within the capitalist context, as Roberto is constantly confronted by his alienation from the working classes he has sworn to protect.

El Diputado provides a true alternative to the main programme by being one of the only celluloid screenings at the festival. The print hums like discovering a secret document. “We looked for more 35mm prints, but that doesn’t affect whether we show the films. There are drawbacks to either format.” More important to Duynslaegher is that the films can have some kind of wrap around, to appeal to audiences through guests: “In an ideal world there are films I would have added, but I had to be real. The fact that Villaronga could travel here makes it very attractive.”

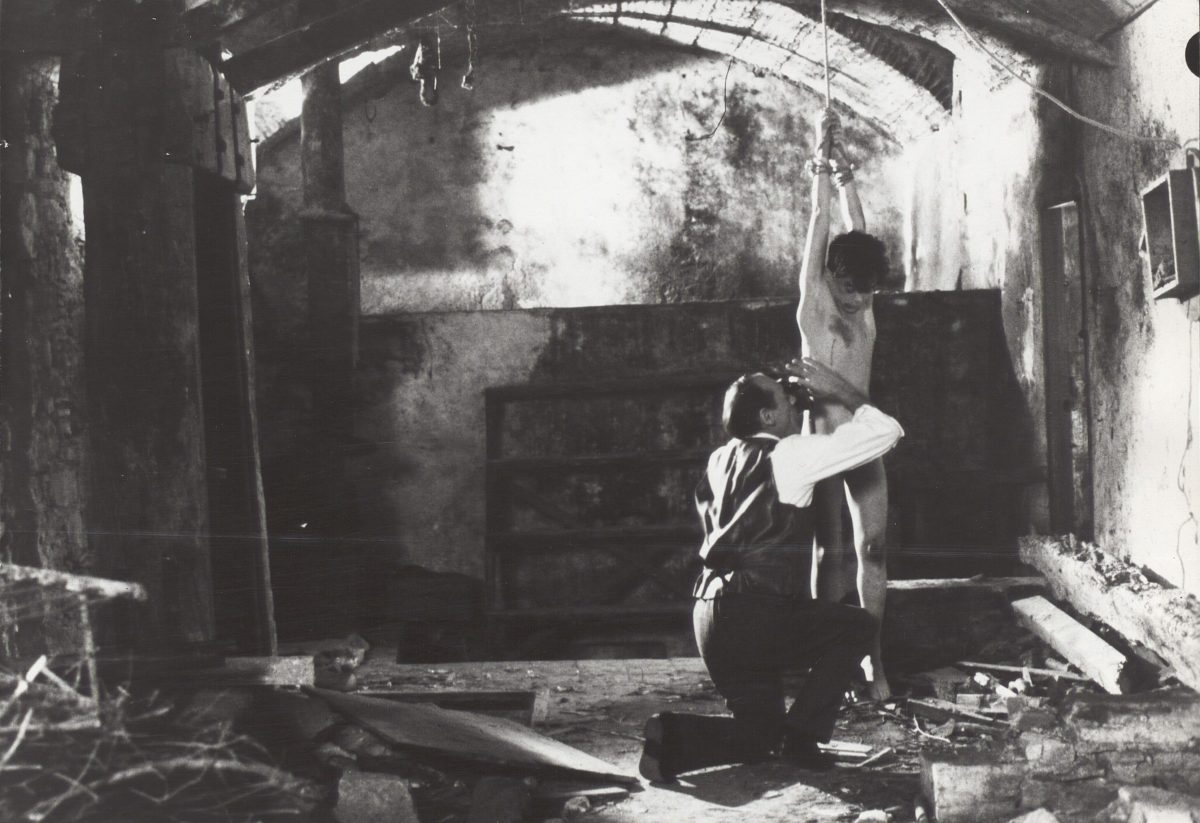

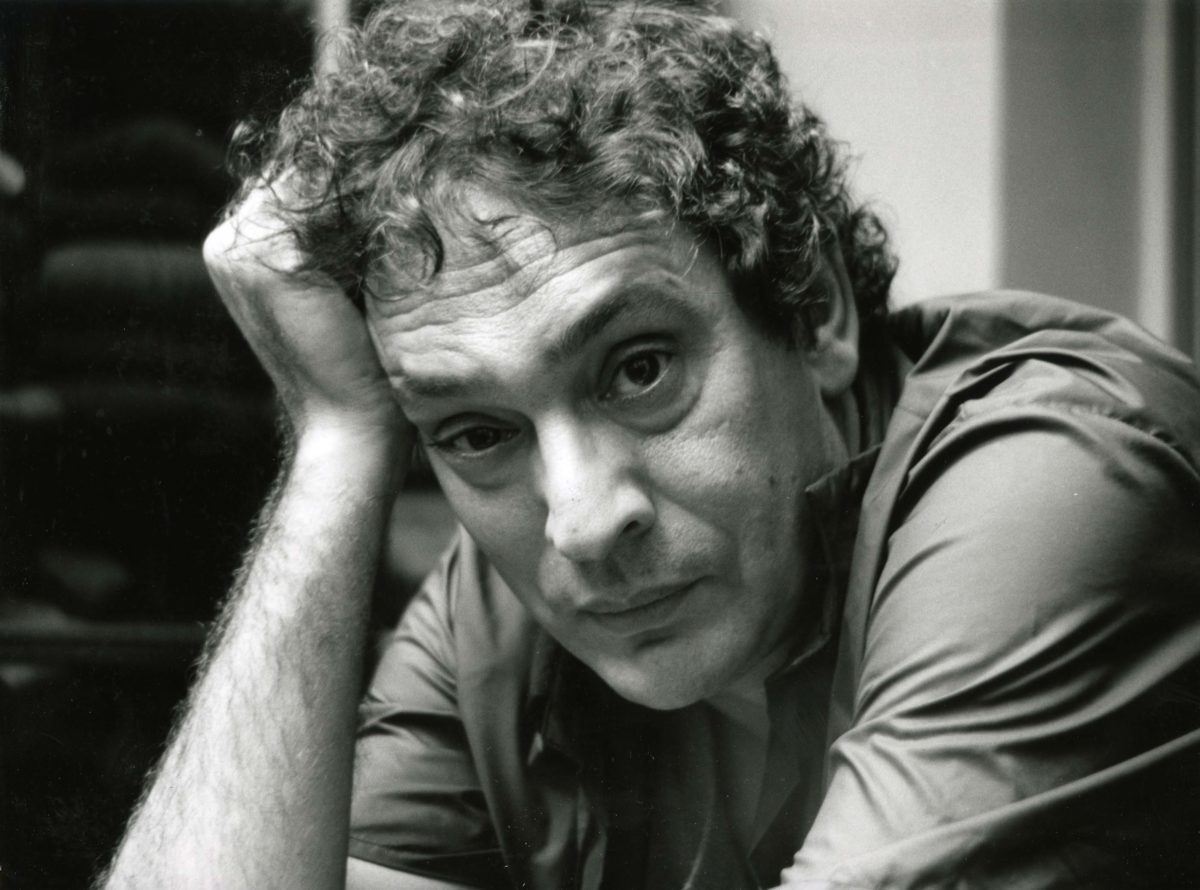

The relatively obscure Catalan auteur Agustí Villaronga is the retrospective’s subject of focus. “My rule was one film per director, then I wanted a bigger retrospective on someone unknown. We show 6 of his 8 or 9 films, never distributed in Belgium. This was a chance to have a classics section with some real discovery. When you see his films in a short time, you know that he is an auteur.” Certainly, Villaronga’s career began with the transgressive thriller to end them all: Tras el cristal (In a Glass Cage, 1986). A Nazi doctor living in gigantic Spanish mansion gets a new carer, Angelo, who happens to be the young boy he raped, come to return the humiliation onto his abuser. A revenge story that by its end literalises cycles of abuse, and equates the lure of Nazism with aesthetics and sexuality, recalling Luchino Visconti’s The Damned (1968). “There was a time in the 70s when the iconography of Nazism became a fashion to show in films in an ambiguous way.” Leaning into this is the performance from David Sust as the grown up Angelo who outdoes even Banderas’ psychopathic turns for Almodóvar. In 1986, Villaronga was apparently slapped in Berlin by an audience member. Tras el cristal remains shocking even today, with its graphic scenes of ejaculation and child torture juxtaposing tender moments of co-dependency. Almost unmentioned goes the fact that Günter Meisner’s Klaus has clearly been harboured in Spain by the Franco regime, living a lavish life of comfort and Catholic values.

“I had dug up Villaronga’s film, saw it in ‘86. It was difficult to see these films because they have never been shown in Belgium.” But Villaronga’s connection to film history isn’t completely unknown. The cinephilic thriller, The Whistlers (Porumboiu, 2019), which plays here, packs its neo-noir storyline full of pop references to John Ford and Arthur Penn. Villaronga actually features in a walk on role as a sinister mob boss, in a move recalling Wim Wenders’ tribute through casting of Sam Fuller and Nicolas Ray as gangsters in The American Friend (1977). Villaronga’s legacy is yet to be cemented, but here in Ghent at least, his significance is clear.

“We have a wide festival audience here so that means we can’t go for anything too difficult in terms of style or subject matter. The paradox of Villaronga is that his films aren’t widely shown outside of Spain, but they are for a large audience because his technique and style is very classical. He isn’t a difficult director to follow.”

Villaronga’s recurrent style is a classicism applied to dark and provocative subject matter, often with the civil war as a backdrop in some way. Tras el cristal is clearly his boldest work, but across his films Villaronga offers a history of his country. “That’s what is interesting in retrospective, that you get to know not only the cinema, but more about the country.”

Villaronga’s latest film, 2017’s Incerta Gloria, is disappointing for its lack of comparative bombast. A civil war-set love triangle, it hasn’t the intrigue to sustain its two hour run time. Gestural performances and sweeping camera pans denote a classical storytelling, but this melodrama doesn’t push its opposing characters far enough. It has value here, however, to illustrate the breadth of a director’s career.

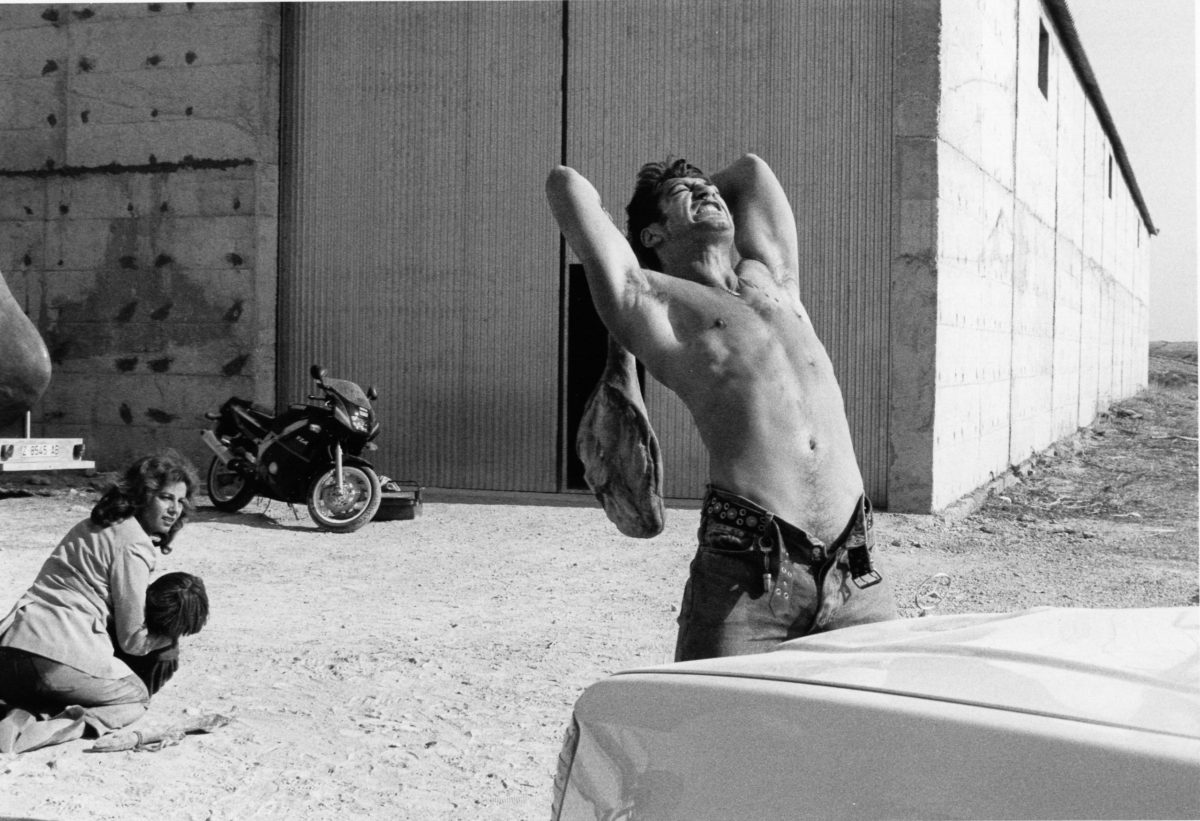

It cannot match the madness of the strand’s most recent non-Villaronga inclusion, Balada triste de trompeta (de la Iglesia, 2010) which has a striking, flamboyant comic-book style. Álex de la Iglesia’s epic, about a circus troupe forced to join the Republican Militia during the Spanish Civil War, is the apex of maximalist cinema, switching formal styles from beat to beat depending on the story’s particular digression. It is satisfying to see clowns taking on fascists in these discord server days, particularly given its commonalities with a recent American clown film. The empty provocations of Todd Phillips’ Joker (2019) are put to shame in this film which genuinely grapples with the clown concept and what it means to be funny as a sad person, and goes to similar extremes of vigilantism as a tool to fix society. Like Tras el cristal, it utilises imagery from the holocaust to comment on the lingering effects of genocidal trauma. Iglesia uses this framework to blitz through the 20th century, with Franco’s death as a major life event in showing the shift through time.

As striking as the film is, I asked Duynslaegher how he justified calling a 9 year old film a classic. His answer is pragmatic: “I wanted to include the director but for one reason or another it was impossible to include his other films, or I wouldn’t have had this one!” The film, full of Sam Raimi bombast and punk energy, succeeds from its melange of cultural touchstones. That de la Iglesia was a child when the dictatorship ended, contributes to the film’s laissez-faire approach to historical trauma. And this is a trend among the younger directors.

Now known for his American thrillers like The Others (2001), Alejandro Amenábar actually returned to his home country this year with While at War (2019), a stately period drama about Franco’s rise to power. He made his mark with Tesis (1996), which reaches to make the Spanish cinema a fully international beast. In it, a student obsessed with mortality gets caught up in a snuff film conspiracy while researching her PhD. Amenábar’s debut is exceedingly slickly produced, a far more commercial prospect than many of the films in the strand; exemplary is a POV shot/reverse shot scene between two headphone wearing characters plays out with each cut switching the music. It’s nothing more than texture, Amenábar flexing his film school skills. A prominent Saura poster gestures to a Tarantinoesque referential metier, and another scene when Angela strokes a TV screen is an obvious reference to Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966). Tesis does also get stuck in some contradictions. There’s a question of enjoying images versus studying them, and a hierarchy of taste within that, which doesn’t get resolved as the film plays out its thrills. At one point a college professor rants that “our country has no concept of film as an industry.” But he is in fact helping the murderer to produce snuff films, perhaps a gesture to Amenábar’s own stance on commercial cinema as inherently exploitative. And yet this movie is so enthralled with the late 80s/90s thrillers of the kind Barbet Schroeder made, that the messages are irreconcilable.

Tesis is irksome because it gives the impression that the freedom to deliver images of senseless violence, where women aren’t punished for loose morality, and there was a cultural space for conflicting ideology, has been taken for granted by Amenábar. Just 23 when he made Tesis, he came of age as Almodóvar and Villaronga were putting out their most confrontational work. His lack of a cause to fight for, or new ground to break, is evident, and so the only taboo left is to shift the national cinema style towards one that resembles Hollywood. You can see this in the ‘softening’ of Luna, the commercial sexiness and international success of Jamón Jamón had such impact that the movement had to change again. This might be unavoidable, as any new expression is eventually capitalised upon by the desires of commercial cinema. The constituents of any movement often morph as their ambitions lead them to take on bigger, international, or more commercially palatable projects. Creative freedom clearly has a price, and it’s the turning of film into homogenised industry. Villaronga, when he can get his films made, puts out increasingly toothless product, while Almodóvar, in settling into his older statesman role, rarely pushes at the boundaries of taste as he once did.

The narrative of a ‘classics’ strand necessarily exposes a potential leak in the Taboo Breaking concept. The majority of choices are a large cluster from roughly 1973-1986, followed by the odd pick from the next two decades. The late Villaronga is there for the sake of completism. It makes these more recent choices seem like the exception, rather than the national rule of taboo busting that the strand celebrates. The pure danger of a Tras el cristal or Viridiana, when paired with the gentle character dramas that make up the Spanish Contemporary Strand, tell a story of a nation slowly morphing toward a universally accepted notion of good cinema, with only Iconoclasts like Albert Serra left to spit in the face of the establishment with their rejection of Spanish cinema history. If curation is an act of criticism, then the Classics strand suggests a time lost, an initial burst of flair which fizzled out after about 15 years. And yet, this is only the story of subversive Spanish cinema as spun by the Classics strand at Ghent Film Festival. Switch out these titles for ten other greats, and an entirely different story of Spanish cinema might be told, that doesn’t rely on the narrative of exuberance and transgression.