The cavil most often raised by sweaty, panting cinephiles at the 31st edition of the Cinema Ritrovato – and a particularly muggy one it was, the much-plagued airconditioning of the Cinema Jolly even more despondent than usual – is pretty much the same as during last year’s festive edition: the too-muchness of it all, the overabundance of riches that turns the breakfast ritual of planning the day’s lineup into an almost Shakespearian moment of doubt and anguish. One option is to follow a particular thread, turning a deaf ear to the sound and fury of well-meant recommendations from friends and colleagues. The structure of the Ritrovato program is pretty well set in stone by now: there’s the ‘Time Machine’ section – a title that would actually suit all of the festival – devoted to the early years of cinema, the centerpiece of which is the ‘Cento Anni Fa’ thread, curated by the indefatigable Mariann Lewinsky, whose archeological forays into the deepest layers of early cinema will still be fêted a hundred years from now. The 50 films from 1917, all projected on 35mm prints, the pristine state of which often begged belief, were in turn divvied up into a number of themes: there were War-themed actualities and fictions like Evgenij Bauer’s Revoljucioner, the director’s most ‘political’ film shot a mere month after the February Revolution and featuring, unusually for Bauer’s studio-bound cinema, breathtaking Crimean landscapes; or Jakov Protazanov’s Stop Shedding Blood!, an exquisitely staged, politically ambivalent comment on the administrative and moral chaos in the wake of revolution. There were also films that showed cinema’s fascination with the ‘dark stranger’, like the Indian prince of Robert Dinesen’s Maharadjahens Yndlingshustru that made a pre-Valentinian star out of Norwegian actor Gunnar Tolnaes, and with the ‘dancing bodies’ of Pola Negri (in her single extant Polish film, Bestia) and Maria Orska (in Die Schwarze Loo), the darling of the Berlin and Viennese art worlds who modeled for Kokoschka. For my money, the two outstanding dance sequences were Stacia Napierkowska’s (the star of Feyder’s L’Atlantide) breathlessly lewd pirouettes in the ‘Orgies’ section of the beautifully restored but otherwise quite silly and old-fashioned Film d’Arte, La Tragica fine di Caligula Imperator, and Lyda Borelli’s entire performance in the diva film Malombra (a Cinematek restoration), which, as curator Nicola Mazzanti accurately described it, is art nouveau come to life. The gothic melodrama about a young woman who becomes obsessed then possessed by a ghost from the past also provided a nice metaphor for the Ritrovato.

Space is the Place

The other large-scale section of the program, ‘The Space Machine,’ highlighted the golden years of Mexican cinema during the 1930s and the Film Foundation’s ongoing World Cinema project, with restorations of classics from the Cuban cinema and three films by the militant Mauritanian-French filmmaker Med Hondo. I hope to catch up with the latter’s West Indies (1979), a musical on the history of slave-owning in the Caribbean that was raved about, when it appears on Criterion’s next World Cinema boxset. I did see a number of Japanese period films (or ‘jidai-geki’) made under the militarist regime of the late thirties, the best of which, Yamanaka’s classic Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937), The Abe Clan (1938) and Fallen Blossoms (1938), managed to combine historical realism and formal control with stringent social and political comment on Japan’s institutions and strict rules of conduct (in the case of the Abe clan, voluntary death in service of the nation).

Tamizo Ishida’s Fallen Blossoms (Hana chirinu), the most visually striking of the bunch, is a closed-setting drama, the action of which is entirely confined to a Geisha house in the Gion quarter of Kyoto that reduces the male clients and the historical action (the civil war leading up to the Meiji Restoration) to voices heard off-screen. As in Hou hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai, of which this film seems a distant cousin, the film refuses to pick a single protagonist amongst a collective of women. The trouble in keeping these characters apart results as much from this lack of individual center and the prevalence of the long shot as from Ishida’s unique aim not to repeat a single shot in the entire film: every angle on the action is a new one, creating a vertiginously articulated space, which led scholar Noël Burch to study the film in ‘parametric’ terms in his study of form and meaning in the Japanese cinema, To the Distant Observer.

‘The Space Machine’ also teleported a number of unidentified flying objects made by director Samuel Khachikian grouped under the title ‘Tehran Noir’. These thrillers made on a shoestring budget between the late fifties and late sixties give proof of a vital Iranian genre cinema that spins off wildly from Indian spectaculars and Western noirs (Delhoreh–Anxiety from 1962 mixes Diabolique with the crime-writer-goes-nuts plot from House By the River and The Unsuspected). Khachikian’s films boast the kind of wacky off-kilter framings, baroque performances and deafening blaring-horns soundtrack (a mix of traditional music and Henri Mancini) that Orson Welles and Robert Aldrich would declare over the top. Oh, and there’s social comment too!

The Classics

Amongst the more established auteurs showcased in the program were the colorists Douglas Sirk (with more Technicolor-is-God bliss courtesy of Imitation of Life and Written on the Wind), Dario Argento (who showed up for the restoration of the De Palma origin tale The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) and told of how of how the film’s Body Double-ish opening scene was the result of a dish of couscous that failed to agree with him), and Nicholas Ray, whose gloriously fauvist Johnny Guitar (1954) was oooh’d and ahhh’d at during its open-air screening at the Piazza Maggiore, which, amongst other things, convinced us that Godard was right when he said this is the most beautiful film in the world, that great beauty can be found in avoiding the color blue (which does not take kindly to the two-color subtractive process of Republic’s Trucolor system) and that Sterling Hayden was one of the most charismatic leading men of his generation, a fact underwritten by John Huston’s restored The Asphalt Jungle (Huston’s great Flannery O’Connor adaptation Wise Blood (1979), introduced by its charming producer Michael Fitzgerald, vied with the Khachikian films for the festival’s David Lynch award). But the main auteurs at the Ritrovato were an unsung hero of the studio era and an actor.

Even Sterling Hayden will agree that Robert Mitchum, during the central part of his career privileged in the retrospective, was the coolest guy in the world. Nobody gave underacting the flair and insouciance Mitchum did, easily beating Cooper in the art of not doing very much at all. I’ve clocked a lot of couch time with Mitchum’s films, so I didn’t feel the need to revisit them in this atmosphere of frantic decision-making, but the single time I did succumb to the droopy-eyed come-hither look on the official Ritrovato poster, I was in for a treat. The movie was Richard Fleischer’s relatively unseen Bandido! (1956), shot on location in the most picturesque parts of Mexico, that gleefully goes off-script and allots generous time to Gilbert Roland – as a revolutionary colonel – to chew the scenery (‘Ay, chihuahua!’) and Bob to nonchalantly toss grenades (‘Samples’) at the Federales from his hotel bungalow.

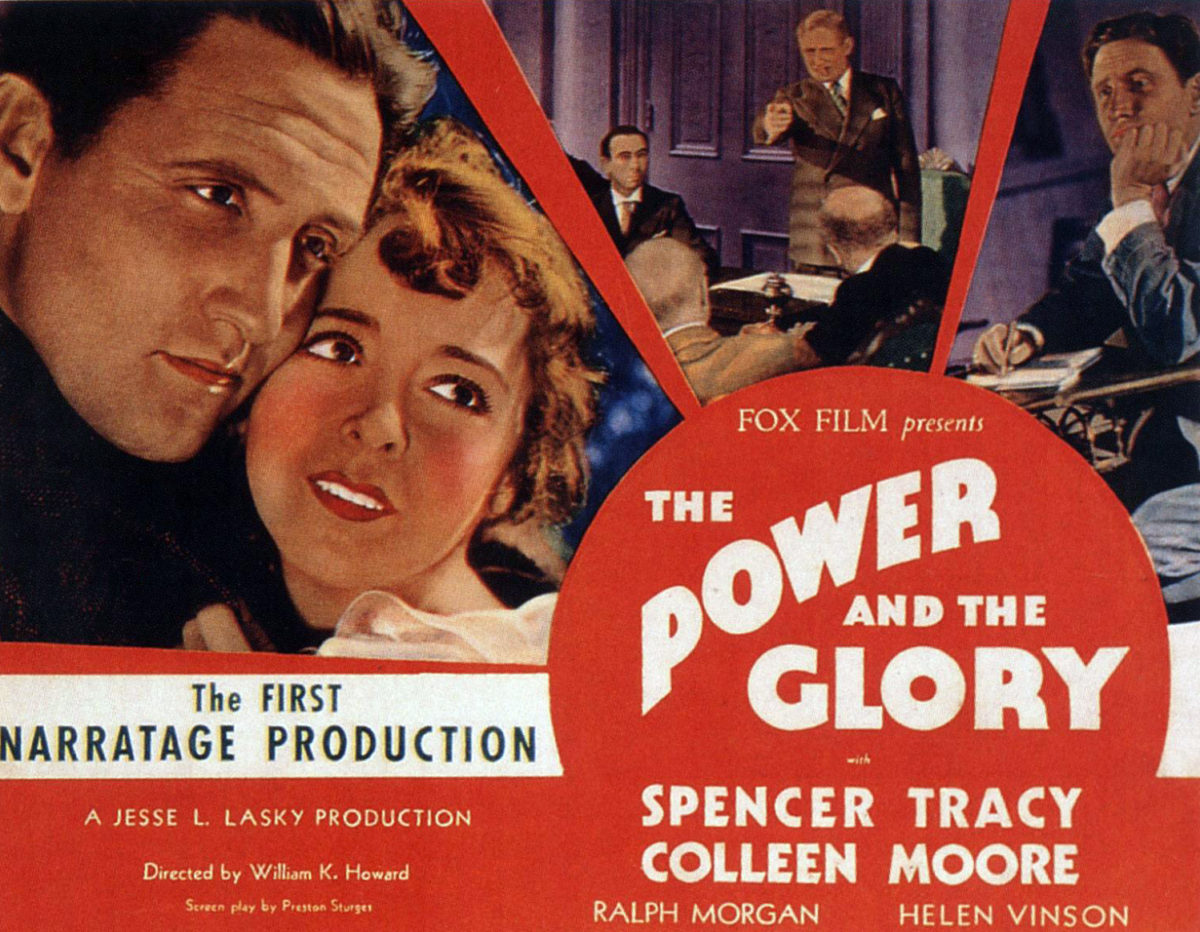

Narratage

William K. Howard never got to direct Mitchum; he died in 1954 virtually forgotten at the age of sixty after a long struggle with alcoholism. Thanks to Dave Kehr and MOMA we were able to take a fresh look at this important figure, whose contributions to the American cinema of the thirties was often attributed to key collaborators like cameramen James Wong Howe and George Barnes and screenwriter Preston Sturges. The two films that I saw in Bologna, Sherlock Holmes (1932) and The Power and the Glory (1933), showed immaculate craft, a particular attention to low-key lighting effects and an exquisite control of tone: just imagine Clive Brook as Sherlock Holmes in granny drag falling into less steady hands! If Howard is known at all amongst non-specialists today, it’s for having directed The Power and the Glory, a movie – about the rise and fall of a Chicago railroad tycoon by the name of Tom Garner – that supposedly influenced Citizen Kane and showcases both a powerhouse performance from a young Spencer Tracy (who at 32 convincingly plays a man in the autumn of his years) and a perfect script from Hollywood neophyte Preston Sturges. Like Kane the movie opens with the tycoon’s demise (by suicide in this case), then proceeds to a series of flashbacks narrated by Garner’s right-hand man and best friend Henry (Ralph Morgan, who starred in the equally experimental Strange Interlude) who wants to set the record straight on a man seen by all as an egomaniacal, cruel powermonger. The flashbacks are not presented in chronological order and jump from the beginning of Tom and Henry’s Twain-like friendship in a backwater town to Tom overruling his board of directors back to Tom in his rail-walking days falling for the local schoolmarm (played with great humanity by silent film star Colleen Moore). At one point Henry’s voiceover provides the dialogue for the characters seen in the flashback, a device that Sacha Guitry would perfect in Le roman d’un tricheur (1936). The New York Times critic reviewing the film upon its release, applauded the “original method of story development” in the film but wondered whether “it will prove as successful with other productions.” The movie’s narrational strategies he resumed as “narratage,” referring to the term Fox used on the movie’s release poster.

Frame narratives and flashbacks, even used non-chronologically, have since become quite common and are especially prevalent in literary adaptations (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, Life of Pi) and Chinese boxes-Russian dolls films from ‘postmodern’ auteurs like Charlie Kaufman and Wes Anderson. Nested stories and frame narratives were in high supply at the Ritrovato: Kristin Thompson mentions the Mexican expressionist horror film, Two Monks (1934), which, from her description, I was sorry to miss. From my end, Protazanov’s Stop Shedding Blood! (1917) made me wonder about the earliest uses of the device and the specific influence from literature and the theatre. In Blood the frame story features two characters, a commissar and his daughter, who explore the contents of secret police dossier that was saved from the angry mob invading police headquarters. They reconstruct from the information in the files the story of a young society woman who falls in love with her father’s Bolshevik secretary and joins the revolutionary underground. At several intervals we return to the father and daughter going through the documents enabling us to gauge the daughter’s reaction of mounting indignation. The story of the young woman, who was betrayed by a co-conspirator, eventually catches up with the present tense of the narration when she is released from prison and is celebrated as a hero by a revolutionary tribunal. The choice for the frame narrative seems relatively superfluous, given that the movie’s theme, the timelessness of injustice and the permeability of class boundaries, is perfectly encapsulated by the narrated story. There is no intent to convey nostalgia and the feeling of time having passed or to stage an encounter between different generations as there is, for instance, in the frame story of The Bridges of Madison County. So it must be that the frame-flashback construction was seen as possessing cinematic or literary value in itself (an obvious move for an industry looking to attract bourgeois audiences). Protazanov was one of the foremost literary adapters, co-directing with Vladimir Gardin one of the earliest versions of War and Peace (1915; Gardin had earlier made Anna Karenina and The Kreuzer Sonata, the latter of which also features a frame-narrative structure). The literary influence on Protazanov’s plot construction is equally evident from his Pushkin adaptation, Queen of Spades (1916), a movie that also features a large flashback section. Pushkin’s fondness for mise en abyme is shown by the structure of his collection of stories Evenings on the Karpovka (1837), to which ‘Queen of Spades’ belongs. All the tales in the collection are set within the frame story of a group of friends gathered to tell each other stories. In the American nineteenth-century tradition of Melville, Hawthorne, Twain and James, frame narratives were equally ubiquitous, although early examples from the American cinema seem more Victorian-Dickensian in nature: while in Edison’s The Face on the Barroom Floor (1908), the story of his downfall told by a drunken artist is still projected as a ‘vision’ insert in the mirror above the bar, in the same company’s The Passer-By (1912), a stranger invited to a bachelor’s dinner tells the story of his life and the crucial moments when it intersected with the woman in flashbacks, framed with camera moves towards and away from the speaker’s face. The ‘life story’ aspect, with all its psychological underpinnings, of the frame narrative shared by Stop Shedding Bood! and The Passer-By also appears in Holger-Madsen’s influential Evangeliemandens Liv (1915), in which a preacher tells a young man about the time he spent in prison.

Nothing but the truth!

The Ritrovato featured another early example with André Antoine’s Le Coupable (1917). That film, written by Antoine and adapted from a tale by François Coppée (1896), alternates the trail of a young thief and murderer with flashbacks from an unexpected confession by one of the presiding judges. Film historian Maureen Turim, in her essential book, Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History, points to Elmer Rice’s courtroom drama, On Trial (1914) as a crucial instance of the cross-fertilization between the cinema and the theatre as regards temporal order. The play begins with the jury selection and the opening pleas in a murder trial, and then devotes the following acts to the testimony of different witnesses, with curtains punctuating the shift from courtroom to the flashback dramatization. The device of the flashback-testimony has since become a standard part of any legal thriller (it’s certainly no coincidence that the game-changer with regard to the use of narrated flashbacks, Kurosawa’s Rashômon, is essentially a courtroom drama). But it’s interesting to see that filmmakers keen to experiment with narration and narrative construction regularly turned to the trial format: the year before The Power and the Glory, Howard directed The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), based on a novel by Kenneth M. Ellis, a movie distinctive not just for its breakneck pace and whip pans, but also for the way Vivienne’s side of the story of the murder of her two-timing fiancé is revealed through a complex series of flashbacks. The Ritrovato program also featured a postwar example with Henri-Georges Clouzot’s beautifully restored La vérité (1960), based on the trial of Clotilde Seggiaro, a young woman accused of murdering her ex-lover (incarnated in the film by an impressive Brigitte Bardot), with which Clouzot wanted to show “the constant ambiguity of the truth” and that “the same event can be shown from several different points of view.” During the trial, the tragic and turbulent life of Clotilde, or ‘Dominique,’ as she’s called in the film, is visualized in flashbacks cued by the different testimonies by friends, lovers and forensic experts, conjuring up tableaux of teenage angst set against the backdrop of a yé-yé Saint-Germain-des-Prés. “Who has never seen La vérité?” Lumière and Cannes festival director Thierry Frémaux asked the crowd at the sold-out screening. That about half of those who raised their hands were under 25, and that, despite its many octogenarian guests (this year including the dapper Angela Allen, a continuity supervisor on The African Queen!) the Ritrovato seems to be growing younger every year, seemed to satisfy Frémaux and festival director Gian Luca Farinelli that the history of cinema was ready for another rewrite.