This year’s nine Best Picture nominees indicate that the Academy has favored films based on original screenplays — six of which were also penned by the film’s director — over films with screenplays based on ‘materials previously produced or published’ or based on ‘materials from another medium’ (as the Best Adapted Screenplay category has been called in the past). Over the years, the writing category has seen an interesting and sometimes puzzling development, which has been reflected in the category’s changing name and subdivisions: the first Academy Awards (which had no nominations, only recipients of the award) distinguished between ‘Adaptation’ and ‘Original Story.’ That year, there was also a separate award for ‘title writing,’ an honor bestowed upon Joseph Farnham (known for writing the titles for King Vidor’s The Big Parade in 1925, but in 1927 he had written titles for at least eighteen pictures, including Mockery and The Unknown, both starring Lon Chaney). In 1928–29 and 1929–30 there was no distinction between adapted screenplays and original screenplays as there was just one broad ‘Writing’ category. The category was split up anew in 1930–31 and in 1935 the terminology changed to ‘Best Original Story’ and ‘Best Screenplay.’ The following years the category changed names a few times over and for a while (from 1940 until 1947) there were three subcategories: best Original Screenplay, Original Story, and Screenplay (i.e. adapted screenplay), which means that for a while the story idea (or the previously existing source) for a picture was awarded separately. This could result in three different wins such as in 1942 when it was decided that The Invaders (by Michael PowellNote that I have added the film’s director in brackets, and not its screenwriters., from a story by Emeric Pressburger) was the best ‘Original Story,’ that George Stevens’ Woman of the Year had the ‘Best Original Screenplay’, and that Mrs. Miniver (William Wyler) was that year’s ‘Best Screenplay.’ However, the year before, in 1941, Here Comes Mr. Jordan (Alexander Hall) had won for both ‘Best Original Story’ (it is a story of a boxer who dies prematurely and is granted a second life in the body of a millionaire) and for ‘best (adapted) screenplay,’ as it was loosely based on a play by Harry Segall, Heaven Can Wait, which would receive its proper adaptation in 1943. ‘Original stories’ could thus be based on an extant source or be completely original (i.e. new, invented from scratch), making this a very fuzzy category. The Academy returned to two writing awards in 1948, for ‘Motion Picture Story’ and ‘Screenplay’ but in 1949 the category was shaken up again by the addition of best ‘Story and Screenplay.’ (I’m confused too.)

Amongst other worries in the fifties — such as how to nominate or award screenplays that had been written by blacklisted or ‘ineligible’ candidates — the Academy clarified the category once again in 1956 by distinguishing between ‘Motion Picture Story’ and ‘Screenplay – Adapted’ and ‘Screenplay – Original’ but the writing category was again reduced to two awards the following year (‘Screenplay – based on material from another medium’ and ‘Story and Screenplay – written directly for the screen’). After this, the category changed names a few times more, but the writing awards remained limited to two. Since 2002 the writing category has been subdivided in ‘Best Original Screenplay’ and ‘Best Adapted Screenplay.’ This terminology is low in ambiguity but it still results in odd pairings: for example, in the Best Adapted Screenplay category one will find remakes, such as The Departed (Martin Scorsese, 2006) based on the Hong Kong crime picture Infernal Affairs (Andrew Lau & Alan Mak, 2002) but restaged in contemporary Boston, as well as shifts in formats (from short film to feature length films) such as District 9 (Neil Blomkamp, 2009) or Whiplash (Damien Chazelle, 2014). Stories drawn from actual events but not previously produced or published in another medium are treated as original material and so you’ll find films based on actual events or persons such as Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2015) and Milk (Gus Van Sant, 2008) under the Best Original Screenplay category together with fantasies such as Inside Out (Pete Docter & Ronnie Del Carmen, 2015) and In Bruges (Martin McDonough, 2008) respectively. Films based on true events or a true story, even if they do not claim to be adaptations, are still likely to emphasize their real-life source, simultaneously confirming and contesting it through an insistence on naming and reiterating that source (an apt observation I am borrowing from Thomas Leitch here).

But back to this year’s (the 90th) awards: it has clearly been a good year for writer–directors. Six out of the nine best picture nominees were directed and written by one and the same person. (Out of these six, only The Shape of Water has a shared writing credit.) The nominations include:

Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Lady Bird (Greta Gerwig)

The Shape of Water (Guillermo Del Toro and Vanessa Taylor)

Dunkirk (Christopher Nolan)

Get Out (Jordan Peele)

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (Martin McDonagh)

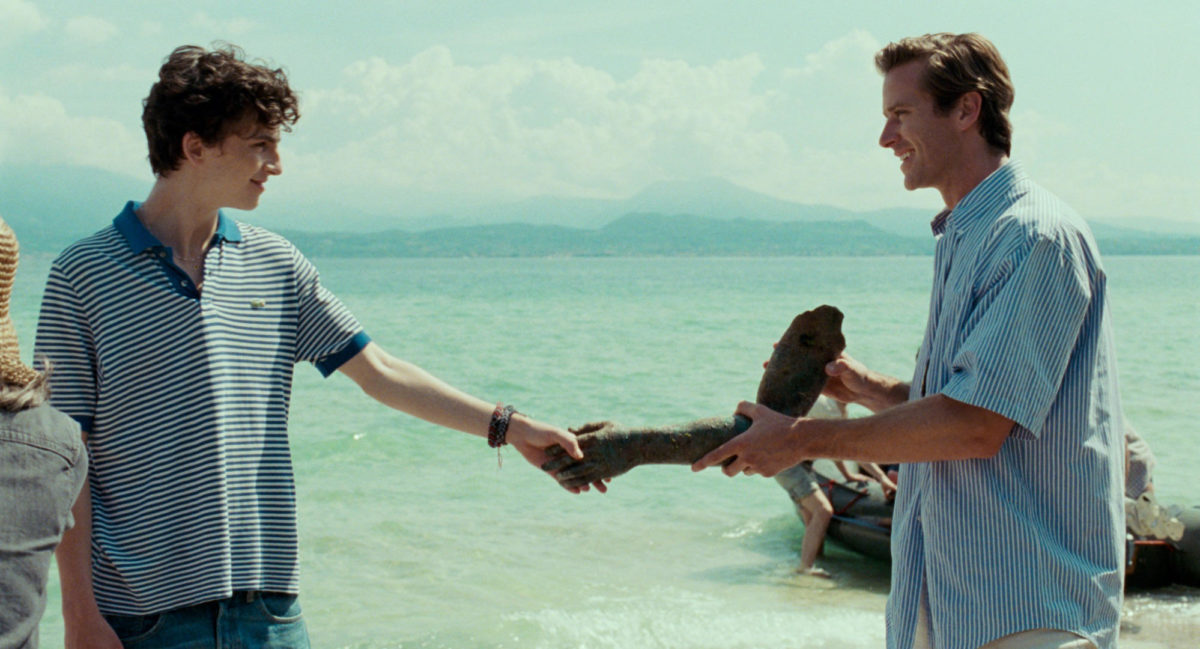

Two of the nine nominations are proper original screenplays (based on true events): The Post, written by 31 year old Liz Hannah, who shares credit with Josh Singer, who after Spotlight must have seemed a solid choice to assist in the rush to get the film produced in a mere nine months, and Darkest Hour, also based on true and partly imagined events from the life of Winston Churchill. Only one Best Picture nominee, Call me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino), is an adaptation, which means that four out of the five films nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay were not considered to be among this year’s best films. (The other four nominees are The Disaster Artist, Logan, Molly’s Game and Mudbound.) It has not been a good year for adaptations.

Books on adaptation theory never tire of telling the reader that cinema, and Hollywood in particular, is heavily reliant on other media. Countless adaptations of our vast literary and dramatic (or otherwise) cultural patrimony have resulted in prestigious pictures; one could say that they have even spawned a subgenre, which critics have called ‘the adaptation genre.’ Deborah Cartmell describes the ‘adaptation genre’ as consisting of pictures that explicitly posit themselves as adaptations (usually adaptations of well-known, classical or canonical works of art) and that focus on (or indulge in) the details of a period setting and costumes, that apply period music, thematize artistic creation (they usually find a way to write the author into the film) and often include what she calls ‘female friendly’ episodes, which can include the insertion of a semi-nude (bathing) man, shopping episodes, intimate homosocial scenes (girly talk), or an anachronistic or at least optimistic assertion of female emancipation. Of course, not all adaptations are based on canonical works or grand literature (Hollywood has always been eager to make films out of contemporary theatrical or literary successes) and thus not all adaptations are part of the genre as described by Cartmell. Moreover, a few notable recent adaptations of canonical works have actively resisted the conventions of the adaptation genre, such as Andrea Arnolds’s Wuthering Heights or Michael Winterbottom’s Trishna (an adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of d’Urbervilles) — the former defies the genre’s ornamental, prettifying and romantic tendencies, while the latter is a re-contextualization of the story’s time and place.

This year’s nominations also don’t really reflect Hollywood’s reliance on or the desirability and prestige of grand adaptations. That does not mean that adaptations haven’t been important to Hollywood for many years. If we look back, we’ll find that adaptations have been part and parcel of cinema history since its earliest beginnings and that they even have played a strategic part in the film industry’s bid at greater respectability, its claim to being called an art, an artistic medium on par with the theater or the novel instead of being associated with low-brow entertainment forms such as the circus, vaudeville and side show entertainment. Films d’art, adaptations of poems, operas, and established literary and dramatic works increasingly became a part of commercial film practice from the first decades of the twentieth century. Partly as a result of this adaptation boom some directors found that they were playing second fiddle where authorship was concerned: studios first promoted the source on which their film was based (Dickens! Shakespeare! Tennyson! Hugo!) and only as a second (or third) afterthought they ascribed creative input and overall artistic authorship to their directors. Directors did not like this. If you have ever wondered why D.W. Griffith had the (petty) habit of putting his name and initials all over his inter-titles, one should consider that he (rightfully) worried about receiving proper recognition (and also, that he was worried that someone would try to steal his work, which was a realistic concern). Other directors — Cecil B. DeMille is a good example — had to negotiate for years in order to get the kind of authorship credit they felt was their due (Sumiko Higashi describes this in great detail in her book on DeMille). Because DeMille usually worked on films based on materials previously published or produced (plays by David Belasco, J.M. Barrie, by his brother Willam DeMille, by Arthur Schnitzler, novels by prosper Merimée, …) his authorship was not easily recognized or at least debatable. (I should mention that, even if his films were original screenplays, usually by Jeanie McPherson, he was still overshadowed in the early days by star or studio publicity.) For the producers, adaptations smelled of culture and respectability and they definitively classed up the industry as a whole, which explains their desirability, but they also laid bare the importance (and the need) to recognize and allot creativity and authorship to all involved in the collaborative medium of cinema. (The adaptation boom also fast-tracked clearer copyright laws.) Later in his life, DeMille would never again play second fiddle, not even when directing and producing his well-known Biblical epics in the fifties. They were adapted from the Holy Book, yes indeed, but they were Cecil B. DeMille’s Ten Commandments (1956) and Samson and Delilah (1949) was his masterpiece. Other examples of directors who actively worked to achieve and solidify their auteur status (despite the fact that they primarily chose to adapt) are Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick and Douglas Sirk, who used a variety of strategies such as artistic or corporate appropriation, thematic consistency, active self-mythologization, undermining the value and importance of the original source and its author (adaptations as a rewriting by a ‘man of the cinema,’ adaptation as a new ‘equilibrium’), sticking to pulp, or reauthoring purportedly ‘unfilmable’ source materials, or, in a reverse strategy, closely associating with the grand artistry of the original author, or encouraging academic readings against the grain etc. (Thomas Leitch and Barbara Klinger have analyzed these auteurs in depth.)

All of this to say that, in short and in a nutshell, the easiest way to make sure no one would mistake a film for ‘just an adaptation’ of another (possibly greater) work, directors could either write original screenplays themselves, or do away with the writing altogether and let the film come into existence on set through artistic serendipity. (Of course foregoing the services of a separate scenario writer for an adaptation was also an option.) Whether actually true or not – because everybody likes a good story and this sure is one – directors such as Rossellini preferred the spur of the moment — luck! Providence! — to a well-written script and movies came into being as they were being shot, not in a pre-production phase as words on a page. Viaggio in Italia (1954), one of his Ingrid Bergman masterpieces, is said to have come together in exactly this way: Rossellini drove around, found an interesting back-drop for his tale of a disintegrating marriage and somehow the locations and what was happing there in real life, structured the film, underscored its meaning and provided it with symbolic resonance. The actual and critical appearance of the ‘auteur’ and the celebration of auteurist cinema illustrate that writing and directing (another form of writing) was key to establishing unchallenged authorship and to ensure creative freedom. The writer-director could have become a challenge to the prestige or presence of traditional adaptations, but auteurs did not dogmatically or necessarily distrust or shun materials that already existed in another medium. Several auteurs quickly turned to (or had always relied on) appropriating or working through original literary, dramatic, historical sources to fit their personal interests and stylistic trajectories. (This is true for Jacques Rivette, François Truffaut, Roberto Rossellini, Jean Renoir, Satyajit Ray and many others.)

But back to the Oscars: If we look at the nominations of roughly the past ten years (2006-2017), we can make the following observations: when there were only five Best Picture nominees, there used to be at least one adaptation, usually more. If a nominated film was based on ‘previously produced or published materials’ it was usually quite recent material, so no big prestigious Jane Austen/William Shakespeare/Leo Tolstoj adaptations on the short list, which can be explained in part by the fact that nobody bothers to make them (in 2005 Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice did not receive a Best Picture nomination). 2006 was an odd year, it had no adaptations of (prestigious, classical, respectable) literary sources among the nominees, but it did have The Departed (a remake), which also won. The presence of the at times charming but utterly forgettable and quite unassuming and non-prestigious Little Miss Sunshine (Jonathan Dayton, Valerie Faris) in the select top five unsettled about everybody. In 2007, three of the five Best Picture nominees were adaptations: Atonement (Joe Wright), No Country for Old Men (adapted script by writer-directors Joel & Ethan Coen) and There Will be Blood (adapted script by writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson). After Little Miss Sunshine, another Indie made it to the top five list that year: the teen pregnancy comedy, Juno, but this film was directed by Jason Reitman, Ivan (Ghostbusters) Reitman’s son, which makes this an ‘Indie from the Inside.’ The fifth nominee was Michael Clayton, a solid moral-awakening-of-a-flawed-attorney picture, based on an original script by Tony Gilroy, who also directed (making this the third writer-director feature of that year). 2008 was a good year for adapted screenplays (four out of five nominated Best Pictures were adaptations), with one even kind of ‘old’ and prestigious: F. Scott FitzGerald’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (David Fincher), the others more recent such as The Reader (Stephen Daldry, based on a book by Robert Schlink), Frost/Nixon (Ron Howard, based on Peter Morgan’s play) and Slumdog Millionaire (Danny Boyle, loosely based on a 2005 novel by Vikas Swarup, which won).

In 2009, the Academy changed gears and decided to nominate nine (or eight or ten) pictures for Best Picture. Fifty percent were adaptations that year, but The Hurt Locker, directed by Kathryn Bigelow and based on an original script (by Mark Boal) won. It has been argued that one of the other Best Picture nominations based on an original script (James Cameron’s Avatar) can be thought of as a remake of Dances With Wolves, and if we follow that reasoning, there were more adapted screenplays nominated for Best Picture than there were original scripts. Writer-director pictures, A Serious Man (Coen brothers) and Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino) were also nominated that year (and of course, being no official adaptation, Avatar was written and directed by Cameron). More writer directors made it to the list the following year: Christopher Nolan was nominated for Inception, so was Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan and David O. Russell’s The Fighter. That year’s winner was an old-fashioned early twentieth century period picture (The King’s Speech), which feels like it was adapted from a tedious play, but was in fact an original screenplay. Six out of nine films were adaptions in 2011, all of them based on recent books or a graphic novel (i.e. Scorsese’s Hugo, based on Brian Selznick’s graphic novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret). The winner that year, Michael Hazanavicius’ The Artist, was inspired by some of the best dramatic and comedic scenes in movie history and on some of its most enduring and charming myths. The film is largely modeled on the filmographies and performance antics of actual classical stars (Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Gene Kelly…), on a bunch of classical films (A Star is Born, Citizen Kane, Singing in the Rain…), on a thrice-told narrative of love and ambition, but it was an original screenplay.

More of the same in 2012: more than half of the nominees were adaptations (including the evergreen Les Misérables, written in 1862, and adapted many times: as a silent film, as a talkie, for television, as a musical, as a manga…), and yet there was still room for the writer directors: Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained and Michael Haneke’s Amour were among the lucky nine. Argo, which is officially an adaptation because based ‘in part’ on Tony Mendez’s book, Master of Disguise, took home the statuette.

More writer directors present in 2013: Alexander Payne, Spike Jonze and David O. Russell were nominated for Best Picture for films based on an Original Screenplay, but they were joined by three adaptations (Philomena, Captain Philips and The Wolf Of Wall Street) and two original scripts. It was another adaptation, Twelve Years a Slave (based on Northrop Solomon’s memoirs) that nailed it.

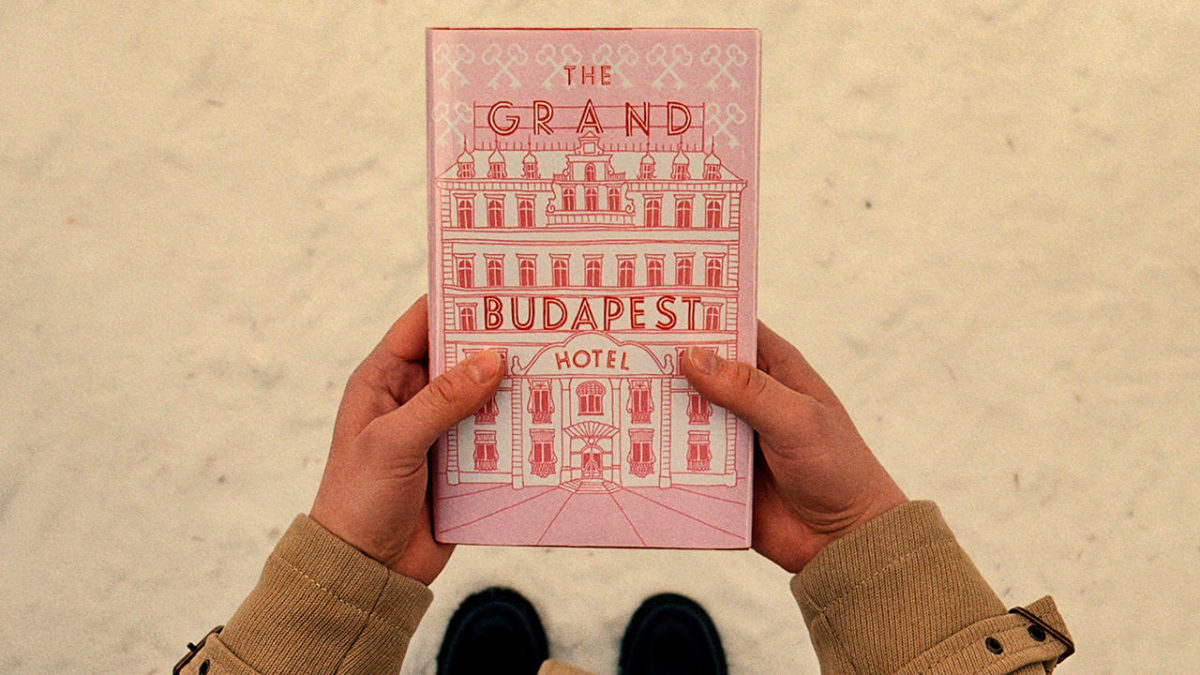

We know now that the number of best pictures nominees fluctuates: in 2014 there were only eight, and an equal number of adaptations and original screenplays, but one of the ‘adaptations’ was the feature length film Whiplash by Damien Chazelle based on his own short. One of the original screenplays nominated for Best Picture that year was The Grand Budapest Hotel, which did it best to look like an adaptation, explicitly claiming kinship to the work of Stefan Zweig, and framing parts of the film as the visualization of an actual book written by a celebrated author. Wes Anderson, a pure and true writer-director (although he did adapt The Fantastic Mr. Fox for which he wrote the screenplay himself), loves literature so much he often invents a literary source or a literary realm to give his cinematic worlds the cultural richness and historical layering they might otherwise lack: consider the various invented children’s (or young adult) books in Moonrise Kingdom (2012) or the book entitled The Royal Tenenbaums (2002) that we see in the opening sequence of the film of the same name. The first chapter of the book coincides with the voice over of the narrator (Alec Baldwin) and the film presents itself as an adaptation of a (fictional) modern Booth Tarkington-type of novel, a book that the world sadly lacks but that exists in Anderson-verse.

2015 and 2016 were adaptation friendly, but again not to the ‘adaptation genre’ as such. The nominated pictures were based on recent materials and set in the (almost) now or recent past, such as The Big Short (Adam McKay, 2015) based on the 2015 book by Michael Lewis or Room (Lenny Abrahamson, 2015), based on Emma Donoghue’s 2010 book. Yet, one could argue that the efforts put into recapturing the fifties via vigorous attention to details (dress, make-up, food, music, slang) make nominated films like Fences (Denzel Washington, 2016), Brooklyn (John Crowley, 2015) and Hidden Figures (Thedore Melfi, 2016), all based on fairly recent publications or stage productions, closely tied to the pleasures and conventions of the adaptation genre.

I wonder whether the ‘adaptation genre’ proper (such as Dr. Zhivago or Sense and Sensibility, Howard’s End, War and Peace, and Anna Karenina) as a commercially viable, popular and multi-awardable Hollywood prestige product is past its prime. Perhaps if a writer-director would take up these canonical sources they would have better chances at finding a willing producer, a ready audience and favorable critical reception? Or, and this might be more likely, the adaptation genre may move house and find that streaming services are better equipped to turn these expensive and (therefore ‘necessarily’) prestigious stories into successful adaptations, consumable by large audiences worldwide, probably in a serialized form (a form, let’s face it, often better suited to the material anyway.) Will the accolades for writer-directed projects turn out to be a trend? Or will the ‘prestige picture’ and one of its most preferred forms, the adaptation genre, find its way back into the race? Time will tell