Upon starting my research for this article with the customary Google search of the person you’re writing about—in this case, Anna Karina—what I found were a bunch of articles about her marriage to Godard and two video-essays: one calling her a muse, the other entitled Anna Karina’s guide to being mesmerizing. And I think the latter one is the best place to start.

The video essay is produced by BFI and consists of (mostly) close-ups or tighter shots of Karina’s face looking beautiful or wider shots of her dancing, taken from Bande à part (1964) and Vivre sa vie (1962). It doesn’t say much about her as an actress or what makes her “mesmerizing”, and it showcases two of her more dramatic films. The way a film like Vivre sa vie that’s, honestly, a precursor of Lars von Trier’s cycle of downtrodden women spat on by societyBut a whole lot less progressive and more condescending. is reformulated to make it about charm is very symptomatic for the way press and, generally, film historians look at Anna Karina. When writing about her, people tend to restrict themselves to mentioning her charm and recycling the same five or six facts about her life. Of course, much of her life (that gets attention) is her tumultuous relationship with Godard, the genius that reinvented cinema.

What’s more, when you look up interviews with Anna Karina (most of the ones in English are from 2016 when she came to America to promote a new restoration of Bande à part), even she perpetuates this way of thinking, by saying she feels honored to be called a muse and comparing their relationship with Pygmalion„[…]she likes being the muse. “How could I not be honored?” she asks me, aghast. “Maybe it’s too much, it sounds so pompous. But of course I’m always very touched to hear people say that. Because Jean-Luc gave me a gift to play all of those parts. It was like Pygmalion, you know? I was Eliza Doolittle and he was the teacher.” – The Guardian.

She’s forever branded as Godard’s muse. She’s heralded for her beauty, style and charm, but seldom has anyone really analyzed what she did in his films—what type of character she played, how she did it, how she was shot etc.

Unfortunately, one cannot speak of Anna Karina in her films without speaking of Godard. Her films with Godard are so much entangled with his perspective that one cannot speak about her work per se—his films are too imbued with his masculine view, especially when gazing at “his muse”. Moreover, in the beginning at least, she was inexperienced and Godard’s characters do not have enough autonomy to be analyzed on their own or as grounds for an artistic interpretation. Everything Godard did was Godard’s more than anybody else’s, especially when it comes to acting. He uses her inexperience, her photogenic qualities, her early uneasiness and later easiness in front of the camera, even her star-power to construct his films, but that does not mean they are any less hers.

Godard Shooting

In a way (or in all ways), Godard is not an actor’s director. He usually does not supply his performers with well-constructed and deep characters and, when he does, his cinematic syntax tends to either shift focus towards his own playful little directorial inventions, or cover the intention and psychology of the character through Brechtian acting. Moreover, his technique of delivering lines during the actual filming of a scene, or giving actors lines to memorize just moments before the camera starts rolling doesn’t leave much time for Stanislavskian foraging through one’s affective memory or finding intentions and building a more structured performance. Nor did he seem to cast actors that were trained in such a way.

Karina often speaks in interviews about how he was looking for actors that were “natural”: “He took actors because he knew they could do what he wanted, like being natural walking around, lighting a cigarette and drinking a glass of something, or sitting down to talk, or run away and do something. He would never take actors who couldn’t do that kind of thing.” And when looking at a Belmondo or Karina performance in a Godard film, it becomes obvious that a certain personal charm was always preferred to gravitas or experience, and it didn’t hurt if you were photogenic either.

Of course, it seems rather obvious taking into account his modernist counter-illusionary ethos that his films would not be constructed in a “classical” way. After all, the reason he maintains an A-list position in film history’s pantheon is his almost counter-cinema approach, which is both playful and political, childlike and pretentious at the same time, and not his skill in producing chilling thrillers or emotional melodramas. That being said, when undertaking an analysis of Karina’s work in his films, we should make clear from the start that we’re not going to be able to rely solely on her take on the part, but a mix of her instincts and tactics and the way the director chose to shoot her.

Notes on a Few Godard-Karina Traditions

Godard’s view of women is a big influence on Karina’s performancesIt’s worth mentioning that Godard tried to convince Karina to give up acting in the beginning of their relationship. in his films. The roles tend to be situated in the sex industry in one way or another. After Bruno Forestier draws the comparison between a prostitute and an actor in Le Petit soldat (1963), Karina will play two prostitutes (in Vivre sa vie and the short Anticipation, 1967), a seductress (Alphaville, 1965) and a stripperAdd to that two cheating women—Une Femme est une femme and Pierrot le fou, leaving only Veronica in Le Petit soldat and Odile in Bande à part untouched by sexual impropriety in terms of Karina’s characters in the Godardian universe. (Une Femme est une femme, 1961).

However, Karina is never (not even in these films) sexualized on screen. She is never nude in any films and never looked at as an object of vulgar desire in the way other women are routinely shown in Godard’s films. (Think of Brigitte Bardot in Le Mépris (1963) or the nude extras in Pierrot le fou (1965) or Alphaville.) That being said, most of her characters do have that to-be-looked-at-ness, constantly demanding the male gaze. And while a Mulveyan analysis of the Godardian oeuvre would prove very laborious and probably not that fruitful (because of his particular and ever changing style of shooting, that always kept the viewer at bay, not letting them get carried away by the illusion and identify with the main male character), it’s worth taking note that a few of the women Karina plays want to become actresses. That they do tend to turn themselves into spectacle (the constant dances In Pierrot le fou she constantly asks to go dancing, bored out of her mind by Ferdinand’s new found interest in literature and philosophy. After that, as I will talk about in this essay, Godard’s perspective on Karina seems more distant, less animated by love.that Karina performs in Godard films), usually in a way that attracts or benefits from the male gaze. Le Petit soldat—the photo shoot; Une Femme est une femme—the stripping scene; Vivre sa vie—the bar scene; Bande à part—the Madison scene. While I’m not being fair by bunching all of these scenes together, it does seem to be a recurring featureA few of the mentioned scenes are very nuanced and would make great examples when analyzed from a feminist stand point—the stripping scene, for example. Where she commands control and, it could be said, subverts the gaze. A comparison between this scene and the ballet scene in Dorothy Arzner’s Dance, Girl, Dance would be really interesting. of Godard-Karina films.

A whole book could also be written about the evolution of Karina’s close-ups in Godard’s films—how they go from fascination, to observation, to careful adoration and finally to nostalgia. But her relation to the camera also changes, as the relationship with the man behind it does—from shyness to content comfort in front of it, from sensuality to coldness, from ignoring it to commanding it. The exchange of looks mediated by the camera is varied and extremely nuanced, interesting on either part of the recording device.

A Spark, but Not yet Sparkling – Le Petit soldat

In his book on Godard, Everything Is Cinema – The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard, Richard Brody argues that all of Godard’s films tend to be inspired by actual events in his life, and, thus, traces an autobiographical link through his filmography. This claim is extended to Godard and Karina’s relationship, arguing—and for good reason—that cinema was a way through which (1) the director conveyed his feelings for the actress and (2) the two mediated conflicts. He saw direct links between formal aspects (the découpage) and dramatic situations and specific moments of the couple’s relationship. Of course, looking at all the films and tracing the ups and downs of their—heavily mediatized—marriage, some scenes clearly synch up.

For starters, the effect Karina’s character has on the protagonist of Le Petit soldat (1961), their first film together. While Victoria Dreyer is, for most of the film, a bit player that only really affects the plot at the very end, she keeps disruptingAnd even then, her involvement in the politics of the film seem rather forced and don’t really go anywhere. the little soldier’s train of thought. Right at the beginning he falls in love with her, just as predicted by his friend. Thus, the almost continuous voice-over that’s mostly made up of Bruno Forestier’s meditations on politics, war or his own particular situation, gets broken up by sudden thoughts of love in the form of questions like: “Did Veronica have Velasquez-grey eyes or were they Renoir-grey?”.

At the same time, when the camera was off, the two were falling in love, and this is what comes through in this first collaboration. The close-ups, her presence (be it on screen or mentioned in the V.O.) tend to be distractions from the main storyline. Just like in a Hollywood film, the heterosexual love subplot is weaved through the film, supplying a break from whatever went on center stage, with the woman especially serving as distraction. The close-ups of Anna’s face very rarely have a dramatic function other than Bruno’s POV, a sort of motivation for his feelings for her. When we see her, we look through his eyes.

The pièce du résistance is the scene where Bruno comes to snap some photos of Veronica for her to use as headshots, so as to pursue her dreams of becoming an actress. The shoot is mostly a long interview alternating light and flirty questions (how many men has she dated, has she ever posed in a bathing suit) to deeper ones (how often does she think about death). For the first part she goes from looking into a hanging mirror and brushing her hair to looking in a handheld mirror and brushing her hair, while moving almost in a Brownian manner around her studio apartment. Through it all, Karina’s performance is kind of monotone, playing a childlike shyness with a slight and uncomfortable smile on her face. As Brody puts it: “Not only did Godard make use of her occasionally faulty French, but he made her hesitations and her awkwardness an essential element of her performance.”

When she puts on Hayden, at his request, she finally bursts out of her shell, starting to joyously prance around the apartment in one of those Karina-happily-dances moments that are featured in almost all of the Godard-Karina films. A burst of energy that stops as abruptly as it began, giving us a glimpse into the childish charm that Godard was so childishly attracted to.

The scene itself interchanged the protagonist and the director, because behind the camera, the actual POV shots were filmed by Godard and then attributed to Bruno. “In the scene, Bruno photographs Veronica while asking her questions. On the set, Godard stood behind the camera and asked the questions himself and Karina responded unscripted—exactly as in Karina’s screen test.” In a way, she’s not acting, but the scene itself feels coherent with the rest of her character because Godard built it around her.

However, the character, apart from her charming shyness, is undefined, precisely because Godard had not figured her out yet. In a way, that’s what he seems to be trying to do in the photo shoot scene. His next films featuring Karina are more varied and she gets a bigger chunk of the main action, with a little more variation.

From Presence on Screen to Actress on Film

The next two films veered towards a more dramatic Karina—Vivre sa vie and Bande à part. The first one was intended as proof of her acting skills, broken into 13 tableaux that all feature contained situations with clearly defined intentions for the actress, containing many close-ups of her face with very expressive Lilian Gish-like eyes. While the actual story, overall, is moralizing, featuring a tragic The bookends are her leaving her husband and her dying. In other words, she gets punished for stepping out of the patriarchal order and fending for herself.end for the wannabe actress turned prostitute, it is the biggest acting challenge for Karina. While employing a good deal of Brechtian elements in the structureA good example is the first tableau, when Karina is breaking up with her husband. The whole scene is shot from behind the actors, making us unable to see their expressions. Forcing us to only listen. of the film (the intertitles for one, the modernist Godardian choices), Vivre sa vie keeps within the melodrama conventions, artificial in a pronounced sentimental/emotional way. With her being constantly under the camera’s eye, the film could have easily become another screen test moment for the young actress, but she’s now a lot more comfortable in front of the camera. While consistently underplaying, she does flash an incredible smile or sensual look towards/into the camera to show us a bit of the woman underneath all the bad luck. She basically finds the exact point of balance between the Brechtian and the melodramatic.

Godard’s technique, more adapted to a styleLonger takes, a richer dialogue, a focus on the protagonist rather than the camera movements or composition (no less impressive, though). that showcases actors, does show Karina’s (who still had little experience at this point) lack of technique. For example, she’s always anticipating the partner’s lines, delivering hers and then turning towards the other character and waiting for their response. Moreover, scenes like the one in which Nana talks to a philosopher puts Karina in a complicated situation when Godard tries once more the technique of mixing one of his own conversations with a fictional character (like he did in the aforementioned Le Petit soldat scene). His questions towards the philosopher come out of Karina’s mouth, but we seldom (if ever) see her react to the answers of her partner. All we get to see of her is her trademark accented phrasing and consistent awareness of the camera, but she doesn’t seem to properly take in what the philosopher is actually saying.

That being said, there are moments of beautiful acting, like the police interrogation, where she admits to trying to steal money and admits her confusion—“I am another”. But my personal favorite Anna Karina performance comes with Bande à part. A film that, she says, saved her life in a dark period—a miscarriage, an overdose, a suicide attempt and a brief period in a mental institution. Playing a naïve girl that foolishly reveals a potential target to two thieves, thus getting involved in their plan to rob her aunt, Karina leaves behind her usual sensuality. Here, her shyness has something of a wild undercurrent. If in the first part of the movie she plays a (beautiful, always beautiful) young girl that’s lived her life mostly indoors, her performance changes as the heist approaches. She moves her body with quick and shaky gestures, the childA mixture that she’ll revisit in Rivette’s La Religieuse (1966), but in a less instinctive, more controlled way. In a film that’s much closer to “classical” storytelling conventions and a more traditional narrative. (and this is the first time that a Karina character reads not as childish but like an actual child) becomes somewhat of a scared animal. The scene of the actual robbing is one of the great examples, she fully embraces the helplessness, creating a perfect balance in the scene. All the elements, the white, austere walls, the eeriness that comes from the robbers with the black stockings on their faces, Louisa Colpeyn’s restrained performance and the wide long shot, all get animated and fall into place thanks to Karina’s vigorous performance, going from terrified and trying to flee, to stunned stillness.

All in all, Bande à part is better proof of Karina’s range than Vivre sa vie—from curiously intrigued in the first scene (which nobody can convince me is not a nod to Lilian Gish in Griffith’s 1919 True Heart Susie), to shily flirting and the varied nuances of being lost in the second part of the movie.

Pierrot le fou brings with it Karina’s most mature performance in a Godard film. In this Bonnie and Clyde-esque film, she plays, a fascinating woman who draws Belmondo’s Ferdinand into a life of crime and, eventually, deserts him. Here, that mixture of ingenuity and sensuality that defined her in previous films goes from sincere to being an act, with Karina modulating the nuances very aptly.

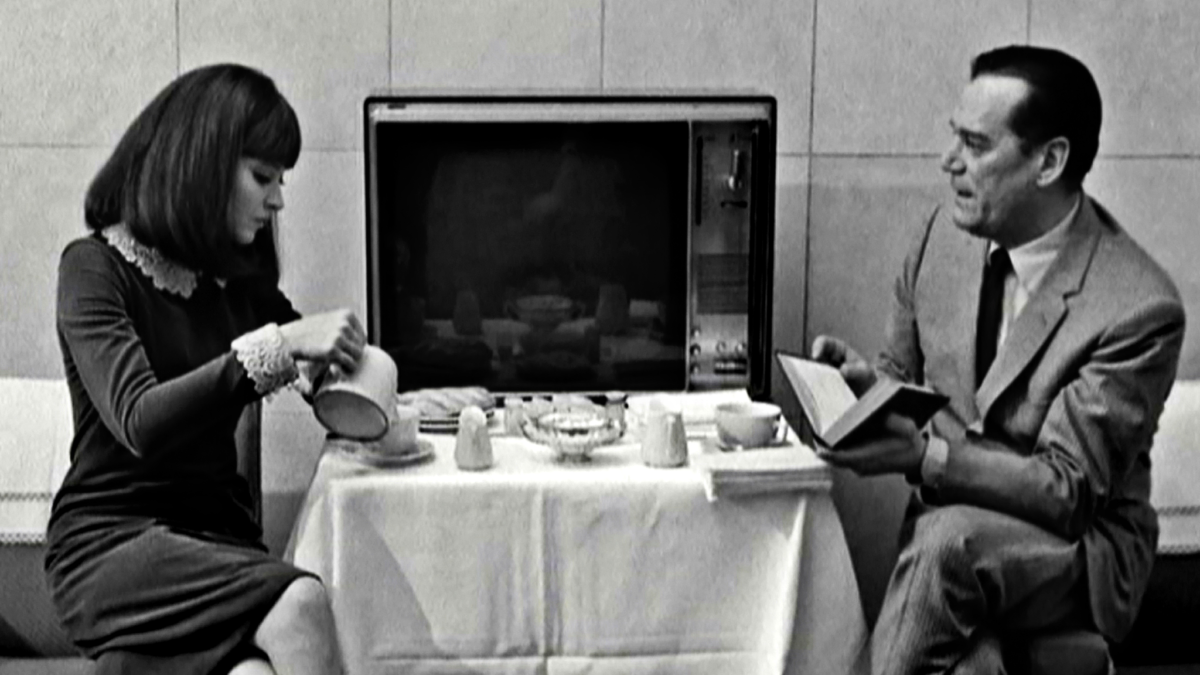

In the beginning, she fascinates Belmondo in contrast with all the other women, who are mere objects of vulgar sexuality that spew constant commercial talk, addicted to material things as the beautiful packaging marketing trainsBoth his wife and the other women at the party recite ad copy to him, one about underwear and the other about shampoo. them to like. Godard uses a party scene (in the vein of a Felliniesque critique of upper class mores) where naked and empty-headed women pop up in every scene (one even literally does so out of a cake!) to contrast Karina, napping in the hallway, her hair up in the same schoolgirl fashion she sported in Bande à part, holding a comic book“La bande des pieds nickels” an anarchist comic book aimed for the youth.. Later on in the film, she too will prove less intellectually inclined than he is, when he starts getting into reading and writing philosophic literature and she gets bored and longs for parties and dance.

In this film, she’s more sexual (at one point, directly asking Ferdinand to have sex with her), and becomes less childish as the movie progressed. Sure, she throws temper tantrums, but that’s more Godard’s take on women, rather than her take on the part. In a way she revisits the confident, self-assured girl in Une Femme est une femme, this time less housewife-y and more fun-loving and adventurous. But her cheating here is not as easily resolved and less contained.

Towards the end, her manipulation of Ferdinand and her disappearance give her something mysterious, but not impenetrable as was the shyness in Le Petit soldat. This time, her actual intentions are hidden by what seems like a carefree attitude, but are, in reality, a front to trick Ferdinand.

In a nutshell, Pierrot le fou has the most well-rounded performance by Anna Karina in a Godard film. Blossoming on screen from child to woman, going from fascination to love and then to ennui and, eventually, to malicious seduction. All very aptly performed by the now mature actress.

Unfortunately, this is where her streak of good parts ends in terms of her collaboration with Godard. Her leaving Ferdinand is a poetic rendition of her leaving him, of her feelings of betrayal towards him. After a tangled web of her cheating, apart from their usual conflicts, their next two (and a half) films lack the chemistry that the two had before.

When Love Goes Wrong, Nothing Goes Right

The last three films that Karina and Godard share are rather lifeless. First, the dystopian Alphaville (1965), then the revisionist Made in U.S.A. (1966), both very different takes on the neo-noir and the last one, Anticipation, a sci-fi short in the La Plus vieux métier du Monde (1967) omnibus. Though the three characters are pretty differentAlthough Natacha von Braun from Alphaville and the hostess in Anticipation do share a robotic quality and are both members of dystopian futures where they can’t emote., all of them lack the usual charm of Karina’s performances.

In Alphaville she plays the innocent daughter of evil professor. What initially seems like a femme fatale turns out to be a lost girl that doesn’t know love or what it entails. The protagonist’s aim is not just to save this world, but also to make this girl feel love again. In the end, he saves the day and is rewarded his much coveted “I love you”.

At this point, Godard and Karina had divorced and, in a symbolic way, the film seems to dramatize a way to get her back. It’s a metaphoric return from her dire present—a “seductress”, an unfeeling prostitute—towards the innocent child, to a place where she needs guidance and protection. Lemmy Caution takes her back in her past and makes her remember who she was, and that she came from the Outer Regions, from a place that allowed for love and didn’t make her degrade herself.

The script gets flipped for Made in U.S.A., where Karina is now the journalist-detective, looking to retrace the last steps of her husband (that Godard voices in the actual film). The film, while still rather flaccid, is, at least, a bit better in terms of how it was shot and the way Godard and Raoul Coutard worked with color (the usual red, yellow, white and blue palette).

Karina’s performance here is more inspired by the traditional jaded detective/P.I, cynical and witty. You see very few glimpses of the childish charm from before: she seems more mature and bitter. Brody argues that this film captures a nostalgia in its many shots of Anna Karina, especially the close-ups. Furthermore, the critic argues that her quest to find her long lost love (her sole reason to live as she makes clear a lot of times: “I did everything for him”) is another metaphor for their relationship, and this time she comes out empty-handed. Writing about the last scene (in which Karina’s Paula kills a writer that had fallen in love with her) Brody says: “This exercise in torment and condemnation was Karina’s farewell to Godard as he had constructed it, forcing her to bear responsibility, on-screen, for destroying him. Godard ties Made in U.S.A. together with a circular structure of hyperbolic accusations: Anna Karina goes in search of him, but he has already been killed; then she finds him again to kill him again. Since he is (in his view) a poet who will tell the truth about her, she has to kill him off.”

I disagree with this perspective, and, while I would concede that there’s something about love in this film that’s autobiographical and is indeed related to their relationship, I don’t think this is it. I can’t even say that the shots are that expressive, even though some of the close-ups are indeed beautiful. Otherwise, the film is too poorly constructed (both in terms of mise-en-scène and narrative structure), that it’s kind of hard to pinpoint what was just lazy and what was intentional. However, Brody’s take on it is so romantic, it kind of makes me want to believe it: “The close-ups are the most expressive ones in color that Godard has made to date, and they are signifiers of the act of remembering. With them, the film appears to exist for the simplest of purposes, fulfilling the primal function of portraiture: to see again the face of a person who is no longer present.”

However, I do think that in Anticipation, he comes back to the sentiments illustrated in Alphaville. Karina, by now, has become the complete antithesis of what Godard was first fascinated with: she’s completely robotic. She speaks of love, but does not practice it. She is a prostitute of “sentimental love”. However, she gets “healed” by one of her clients who fools her into kissing.

“The antithesis of prostitution was, in Godard’s view, love” says Brody. Both in Vivre sa vie and Alphaville, the women give up their profession once they find love (or at least they want to). So, on a smaller scale, the same sentiment of Alphaville is what he intends here. Although, here, a few jabs at Karina could be discerned.

For example, in the grotesque scene of her being sprayed with water, with her tongue in the air, sloppily trying to catch it, which Brody mentions as well. What he doesn’t mention is the way she is dressed, in a white ruffled shirt, somewhat similar to the one she is wearing in Le Petit soldat, the one he bought her at the beginning of their relationship, after their first night together“We went to his hotel. The next morning, I didn’t wake up, and he left before me and came back with a beautiful white dress. I wore it in Le Petit soldat. Just for me. Like a wedding dress, you know.” – Filmmaker Magazine. Only now it’s part of a costume, a grown woman pretending to be a doll. But Karina does not play her like that, it is Godard who builds that situation around her. He even makes her stand in front of the mirror and comb her hair just like in Le Petit soldat, but this time with a big, oversized comb. However, she is not that Karina anymore, and her performance reflects it.