Irm Hermann was one of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s early confidants. She was 21 and a secretary for an automobile club in Munich when she met the 20-year-old director at a reading of a play for which he had won a prize. For her, it was love at first sight. A year later he convinced her to play a part in his very first short film, Stadstreicher (1965). “I can’t act. I’m not an actress,” she protested.

That Fassbinder’s oeuvre was so voluminous—11 plays, 2 radio plays and 45 films, including a five-part and a fourteen-part television series, in a period of 13 years, from 1969 to 1982, the year of his untimely death—is largely due to the stock company of actors he gathered around him. In order to tie all of them to his person and to avoid them working with other directors, the professionally possessive Fassbinder was forced to make films almost continuously. Or, as his biographer Robert Katz put it, he was “filling his life with followers in order to make movies, then making movies to fill his life with followers; finally, the distinction would disappear.”Katz, Robert & Berling, Peter. Love Is Colder Than Death. The Life and Work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. London: Paladin Books, 1989. p. 39

Especially the women in Fassbinder’s acting company were crucial to the type of cinema that was most dear to him: contemporary, critical melodrama that updated Douglas Sirk’s fifties weepies as well as laid bare the malaise and flaws of the Bundesrepublik in the turbulent seventies; a cinema that, as the genre prescribes, deals with feelings, emotions and passion. Or, just the other way around, a cinema that examines the suppression of these affairs of the heart. This favorite theme of the Wunderkind of the Neue Deutsche Welle was personified by Irm Hermann.

Fassbinder claimed that in his emotional life he could identify most intensely with women. According to Harry Baer, occasional actor and jack of all trades on his film sets, Fassbinder thought he could tell a story more easily with the help of women, because he found them more transparent and offering him more opportunities than men might. Every actress in the Fassbinder universe fitted a certain profile, often based on Hollywood types. To one extreme there’s the spontaneous, spirited sensuality of Hanna Schygulla, the actress who stuck with Fassbinder the longest—from Liebe ist kälter als der Tod in 1969 to Lili Marleen in 1980—and whom he mostly used for her star quality, having her play either the dumb blonde (the Marilyn Monroe type) or the vulnerable ingénue (Loretta Young style). At the other extreme, there is the vamp, incarnated by Ingrid Caven (Warnung vor einer Heiligen Nutte, 1970; Der Händler der vier Jahreszeiten, 1971), who acts as an erotic icon and sings in smoke-filled cabarets and transvestite bars, embodying the femme fatale à la Marlene Dietrich. Neatly in between is the versatile Irm Hermann, peeping, sneaky, hypocritical, with a squeezed-shut mouth, slanted eyes and a slim, even graceful body, often hidden in a shapeless baggy dress. She stands for everything that Fassbinder hates in the modern German Hausfrau, which he blows up to caricatural proportions. The mundane middle between two oneiric extremes. Then there are also Margit Carstensen (Martha, 1973; Angst vor der Angst, 1975) and Brigitte Mira (Angst essen Seele auf, 1973; Mutter Küsters Fahrt zum Himmel, 1975). The first, bourgeois, elegant, lean bordering on the anorexic and often mentally humiliated; the second, proletarian, deadly honest, gullible and therefore also a victim.

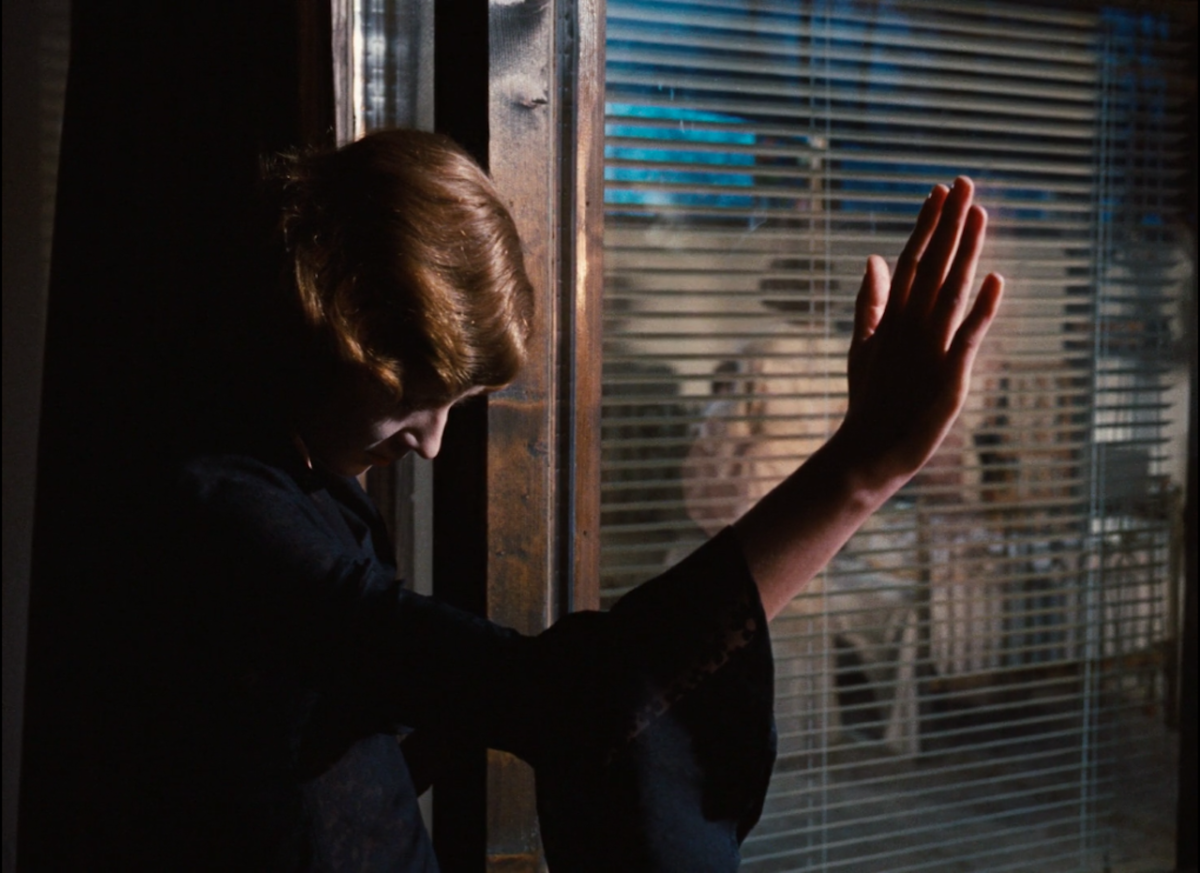

Unlike Hanna Schygulla, Margit Carstensen, Brigitte Mira, Elisabeth Trissenaar (Bolwieser, 1977), Barbara Sukowa (Lola, 1981) and Rosel Zech (Die Sehnsucht der Veronika Voss, 1982), Irm Hermann was never rewarded with a leading role. The only time she came close to being the star, in Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant (1972), she still played third violin to Hanna Schygulla and Margit Carstensen. In this lesbian huis clos, Hermann is the slavish secretary of a successful fashion designer (Carstensen) who is in love with a younger woman (Schygulla) of humble origins. Throughout the film, she spies on the sadomasochistic pas de deux, does not open her mouth and is humiliated and belittled by her boss. Still, you feel like she’s somehow pulling the strings. Like Miss Danvers (Judith Anderson), the governess in Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), her black silhouette is omnipresent. In a surprising turn, she achieves a small triumph in the end.

Fassbinder said that Petra von Kant was much more directly autobiographical than Faustrecht der Freiheit (1974), which nonetheless dealt with gay men and in which he himself played the lead. Die bitteren Träne der Petra von Kant—based on a play authored by Fassbinder—appears to be the film in which the dynamics between the characters most strongly reflects the power struggle that invariably took place during Fassbinder’s shoots, in which Irm Hermann was often his grateful dupe. He called her a “born victim” and gave her corresponding roles. In Warum läuft Herr R. Amok? (1969) she plays the neighbor who, in a shocking scene, happens to knock on the door of Herr R., cannot stop talking about her skiing holiday, upon which Herr R. kills her with a heavy candlestick and then makes his wife and child suffer the same fate. In Der Amerikanische Soldat (1970) she is a drunk prostitute who is thrown from a car by an American hitman. In Pioniere in Ingolstadt (1970), she plays cynicism incarnate as a young woman who hangs out with every soldier in a musty provincial town and is taken by one of them on the park bench in a joyfully uncomfortable scene. In Der Händler der vier Jahreszeiten (1971) she gets a beating from her dipsomaniac husband, a fruit seller whom she treats unlovingly until the cold selfishness of the women around him drives him to an act of despair.

Contrary to Hanna Schygulla, who seems to float in higher spheres, Hermann has her feet planted firmly on the ground. In four films, she plays a petit bourgeois shrew who cannot cope with family scandals threatening to disrupt her comfortable life. In Angst essen Seele auf (1973), she is the nagging daughter of the 60-year-old cleaning lady who falls in love with a Moroccan guest worker half her age; in Mutter Küsters fahrt zum Himmel (1975) she plays once again a daughter-in-law, this time of the widow of a laborer who kills his personnel manager in protest and then kills himself; in Angst vor der Angst (1975) she is Lore, the sister-in-law of a housewife (Margit Carstensen) who suffers from inexplicable fears and completely loses control. Yet, however much his actresses played a fixed role, Fassbinder took pleasure in casting them against type every now and then, preferably in a small part. In the fairground-set opening of Faustrecht der Freiheit, Hermann briefly appears as the boa-clad Madame Chérie, a colleague of Fox (Fassbinder), the “Talking Head”.

At the beginning of their career, Fassbinder asked Hermann to become his agent, which she tried—at her own expense. Together with Kurt Raab (actor and set designer), Peer Raben (composer) and Hannah Schygulla, Fassbinder founded the Antitheater on the ruins of the Action Theater. He formed a ménage à trois with Hermann and Raben. In practice, Fassbinder and Raben shared Hermann’s bed, who herself slept on the floor of her small flat. At one point, Kurt Raab also moved in with them. “He kept switching partners. It was all very difficult and new to me. It went completely against my middle class upbringing. But I was totally dependent on Rainer and at the same time I wanted to protect him and meet his needs,” she later said. Hermann was assigned various tasks, including finding money to finance their first full-length film, Liebe ist Kälter als der Tod (1969), in which she only has a cameo. Between 1969 and 1981 she was featured in at least one Fassbinder film every year, bringing the total of their collaboration to 19 titles, 17 cinema and television films and two television series. It might have been more if Hermann hadn’t worked with other directors in those years, something that annoyed Fassbinder immensely; he found this disloyal and as punishment, unfaithful actors were suspended for several months or years, or, in the case of Kurt Raab, even permanently expelled.

Hermann continued to do all kinds of odd jobs in between acting, and she remained loyal to Fasssbinder no matter how much he harassed and belittled her, or accused her of treason. She often broke down in tears, had fits of anger and blamed Fassbinder for promising to marry her and have children. (Eventually Fassbinder married anyway, but not to her, but to a rival: Ingrid Caven. They were already divorced two years later.) Anyone who disappeared from Fassbinder’s life also disappeared from his films. “He needed a black sheep. Someone always had to fall out of favor,” Hermann recalled. At times she was desperate, she even tried to commit suicide, but she always returned, as if she could not separate herself from him physically and psychologically. She found some relief in Indian mysticism, Buddhism and a macrobiotic grain diet (in one humiliating scene, Fassbinder forced her to stuff herself with meat, until she vomited).

When Fassbinder staged Frauen (based on the Claire Booth Luce play from 1937) for the Hamburger Schauspielhaus in New York in 1977, Hermann was one of forty actresses—there was not a single man in the play nor in the film adaptation. In the meantime, she became pregnant, not by Fassbinder but the painter-writer Dietmar Roberg. When Fassbinder proposed to her anyway and wanted to adopt the child, Hermann was faced with a dilemma whose solution would determine the rest of her life. In the end she did not follow her heart, but her mind, opted for security and married Roberg. The child, a boy, was baptized Franz, at the suggestion of Fassbinder who had identified all his life with Franz BiberkopfEvery Franz in his films (there were nine) was always a self-portrait, regardless of whether he played that part. For the films he edited himself, he invariably credited himself using the name Franz Walsch, a reference to one of his favorite American directors, Raoul Walsh., the protagonist of Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz. Apart from two small roles in Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980) and Lili Marleen (1981), Hermann’s collaboration with Fassbinder was over. In the few years that Fassbinder had left to live, she struggled with the international success that finally came to him: she had always dreamed that she would one day share this success with him.

Irm Hermann was just as much of a workhorse as Fassbinder himself: in addition to her parallel career as a stage actress, she acted in 169 movies, television films and television series. She was certainly not picky. While she worked with other talented filmmakers from the Neue Deutsche Welle during her dozen years with Fassbinder—such as Volker Schlöndorff, Reinhard Hauff, Peter Zadek, Herbert Vesely, Hans W. Geissendörfer, Werner Herzog—in the post-Fassbinder era, her occasional collaborations with Ulrike Ottinger, Percy Adlon, Herbert Achternbusch and Rudolf Thome drowned in a sea of German Kitsch and clownery, Heimat films and the inevitable krimi of the endless Tatort television series. Remarkably, her overflowing filmography of low and middle brow ‘Germania’ also includes three films by the controversial and provocative cult figure Christoph Schlingensief: Das deutsche Kettensägen Massaker (1990), Die 120 Tage von Bottrop (1997) and Freakstars 3000 (2004).

But it is ultimately for her Fassbinder films that Irm Hermann will be remembered. She ran like a silk thread through his filmography; regardless of the time allotted to her characters in the narrative, she portrayed them succinctly and wittily. With her often minimal screen time and sometimes seemingly insignificant bit parts, she left as big a mark on the work of Fassbinder as divas like Hanna Schygulla or Margit Carstensen.