Archival Footage at IFFR 2017

In the digital age, it’s easy to forget about films existing as a specific medium, especially since so many of them are cloned to BluRay or VOD platforms soon after their release, and the works themselves seem to be safe from any damage that their individual copies might suffer. While watching on the big screen the scratchy or dissolved surface of the archival footage in John Torres’s People Power Bombshell: The Diary of Vietnam Rose, or Bill Morrison’s Dawson City: Frozen Time, we might wonder at the frailty of film stock that once seemed eternal, and still not imagine that any current day equivalent might suffer extinction.

However, at the 2017 edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam that recently came to a close, one ardent cinephile wanted to prove the contrary. A year after the IFFR debut of his compilation Bigger than The Shining, Mark Cousins (best known for his 15-hour series The Story of Film: An Odyssey) wanted to come back to the festival to destroy it in front of the audience. As we entered the screening room, an axe was in place on a platform, ready to smash the DCP into unreadable shards of plastic and metal. One last cinema screening preceded the fatal event: before our eyes again were fragments of Nicholas Ray’s 1956 Bigger than Life intertwined with Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 The Shining, occasionally put into perspective by Cousins’ silent, terse intertitles: “What if one film is a premonition of another?” In their new alternating order, these scenes from otherwise cinematically different works truly seem to echo one another. Both display a masculinity crisis that leads to a breakdown of the nuclear family – in simpler words, the man of the house resigns from his role; in both cases (James Mason’s teacher character as well as Jack Nicholson’s writer), he claims to have a superior intellect to what his wife can keep up with and consequently holds her in contempt; in both cases, he turns homicidal and threatens the life of his son. Since these films were characteristic for their respective eras, in re-cutting the two films, Cousins is striving for a bigger point still: that the prototypical Eisenhower era man in a grey flannel suit would also blend in with the crowd under the Reagan presidency. (And will history repeat itself anew with Trump’s reactionary and monolithic empowerment of white middle-class men?) A feature-length video essay, Bigger than The Shining brings sufficient material from both of these films so that we can make out their plots and yet stays focused enough to bring out their similarities. Technically, its reworking falls under the Fair Use copyright exception, but then again, the initial editorial use might eventually lead to commercial use – at the screening, addressing the audience as well as curators Dana Linssen and Jan Pieter Ekker, Cousins revealed his reason for destroying the film: he was concerned that somebody, someday, might make money off this film that exists without permission from the copyright owners of either Bigger than Life or The Shining. He alluded that it’s better to give it the axe before this happens and send it back to the realm of cinephile thought experiments – and he did, right there in front of the film’s second IFFR audience. Everybody else who (to Cousins’ knowledge) had a digital copy of the film received an email asking them to delete it. Bigger than The Shining now belongs to the memory of those who watched it and haunts the texts of those who wrote about it – an absent presence, potentially nowhere to be found, after a one year existence in the age of digital reproduction.

Cousins’ dernière screening and its subsequent sense of loss also worked as a great introduction to watching films in the ‘Regained’ section: a regular thematic program at the IFFR, ‘Regained’ focuses on cinema history, lost and rediscovered films, unsung heroes of bygone days. Its highlights are not necessarily the most immediately appealing titles (more on that, later), but they are found in what often seems like niche topics which blossom into comprehensive meditations on cinema and the past. Bill Morrison’s 2-hour essay film Dawson City: Frozen Time is one such pleasant surprise. Going back in time further than the first cinema screenings, back to the Dawson City gold rush that flooded the area with prospectors, the filmmaker uses period photographs to show the courage and innocence of these late-19th Century trekkers. (The screening I attended got a big audience laugh when, listing the opportunistic local businessmen who sold tools and accommodation to the newcomers, Morrison mentions Donald Trump’s grandfather.) Dawson City soon became the site for frequent film screenings – several silent films being topical to the gold rush (and yes, Charlie Chaplin’s 1925 The Gold Rush was among them). For the sake of cost reduction, the motion pictures in store were all printed on nitrate film stock, even when less flammable (though more expensive) alternatives existed, and fires were a regular event at screening venues – Morrison includes photographs of the Orpheus theatre being severely burned down, not once, but twice.

Ultimately, Dawson City: Frozen Time is about the frailty of archival evidence in cinema, this technology handled more often in terms of profit than of historic or artistic value. Much footage that didn’t go up in flames was thrown in the Yukon River for lack of storage space; thousands of film reels were buried under an ice hockey rink. It would seem like an appalling culture crime for early-cinema exhibitors to abandon such a rich archive because “the patrons now want to see talkies”, but in the hands of Bill Morrison it takes on complexity. His 2002 damaged-found-footage film Decasia, similarly reminding us that film preservation is the only way of opposing the action of time, nonetheless revels in this memento mori of partly erased film stock. Images come into view, then hide behind film defects, only to become visible again a few seconds later after the damaged part of the film stock has unfolded. Variété scenes are given immeasurable pathos by suggesting that the bodies shown on film, much like the stock itself, have decayed since the exuberant moment still flickering on screen. Likewise, the Dawson City Collection is a testament to a once-flourishing community brought together by the Klondike Gold Rush and later scattered by the rumor that treasures were to be found somewhere else. Every scratch and blur on the recovered film stock is a synecdoche of the same tale.

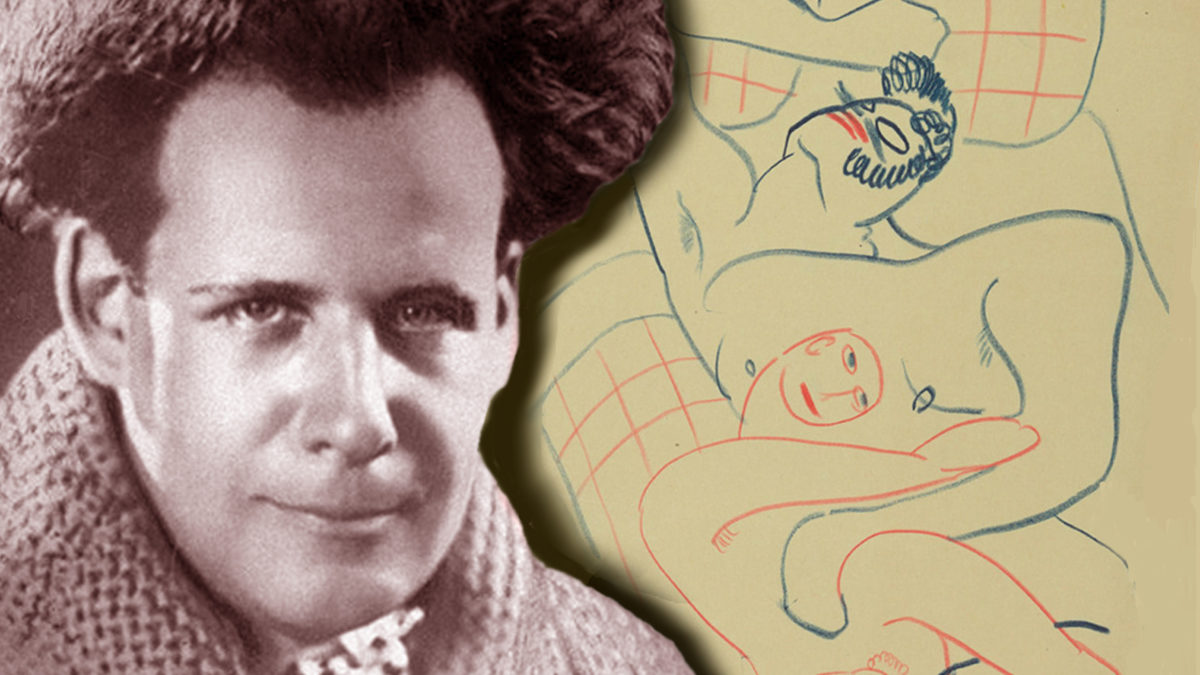

Not everything has to be lost to be rediscovered, though, as one could easily conclude after watching Mark Rappaport’s Sergei/Sir Gay. An actor presents a monologue in voice-over that is ostensibly a first-person account of Sergei Eisenstein’s sexuality as it appeared hidden in plain sight in his Marxist films. In pointing out Eisenstein’s attraction to the young men in his films, Rappaport’s latest video essay borrows many techniques (and some sailor films footage) from his 1997 feature length The Silver Screen: Color Me Lavender, which was a chronicle of homoerotic subtext in mainstream Hollywood films and re-contextualized and re-associated so much material that by the end it was hard to believe any Hollywood film to be heterosexual anymore. Arguably, a lot has happened in the past two decades to prepare the field for the Soviet master’s worker strike tragedies to be reappraised as gay erotica: the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! sailor dance scene has given a voice & choreography to seamen’s frustrations with not having women around (to Rappaport, it’s like Color Me Lavender made it into the mainstream – he of course quotes the Coens’ scene in this film); Peter Greenaway’s Eisenstein in Guanajuato frames Eisenstein’s exit from the USSR as an exploratory journey that reawakens his senses and latent homosexuality. The beauty of Rappaport’s endeavor is that there is a lot less speculation to it than in a fiction film – he merely takes the footage of one preferred actor which Eisenstein repeatedly directs into pietà poses, or a dubiously steamy shot on the sailor’s deck where the men are all sleeping half-naked and gently swimming in their hammocks; as we watch these images, the commenting actor’s strongly accented voice hints at the subtext, by now pointing out the obvious. Eisenstein’s homoerotic drawings (which he signed with “Sir Gay”) further indicate him as a fetishist. The ultimate purpose of Rappaport’s playful narration isn’t as much to expose Eisenstein’s repressed urges (as if he were thinking dirty thoughts while paying lip service to the worker’s revolution), but to show how weirdly harmonious his fetishes coexisted with the Soviet montage rhetoric of energizing the spectator into building a new society.

The IFFR 2017 lineup proves just how much can be done simply by re-cutting preexistent footage. ‘Regained’ also included a Ross Lipman footage-assisted lecture on Bruce Conner’s Crossroads, which uses recordings of nuclear explosion tests to reflect more broadly on the atomic era. Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s What Happened to Her zooms in on the gory details of female naked bodies portraying corpses in TV shows and films; these scenes theoretically reflect on women’s vulnerability and hint at society’s responsibility to protect them, but actually contain an undeniable erotic element: the ‘corpses’ are invariably young, beautiful and shot in erotic poses, always discovered by men who take note of the violent and often sexual circumstances of their death. The filmmaker includes in voice-over a behind the scenes testimony of the direction actresses get when appearing in these roles. By making us reflect on women’s humiliating experience while posing as TV crime show corpses, and through the mere quantity of young ‘dead’ female bodies that it brings together, What Happened to Her exposes the underlying misogyny of the brainy, assumingly asexual narrative thread of crime investigation.

Collage can also be used to illustrate rather than analyze, and this doesn’t necessarily limit its creativity. Michael Almereyda’s Escapes is a 90-minute long interview with Hampton Fancher, an actor, producer, director, screenwriter of Blade Runner and natural-born storyteller. His life story is not the typical steadily rising star trajectory, but he seems to have enjoyed his life in Hollywood and is more than able to evoke that enjoyment. His anecdotes might also give a clearer impression of the ever-changing Tinseltown milieu than the average actor’s biopic. For roughly the first half of the interview, while Fancher’s voice engagingly recalls a tale of his effervescent youth, Almereyda and editor Piibe Kolka use fiction film footage to an approximation of the same dramatic situation, sometimes seeming to keep a scene in its entirety – its couple dynamic or power play matching what’s being recounted –, otherwise cutting in an obviously intrusive way. For instance, there’s a cut from a color shot of a young man and woman talking at a table, at the moment they both look up, to an outdoor shot, in black-and-white, of a villainous-looking cowboy stepping away from a swinging bar door; Fancher’s voice-over goes on about how he tried to persuade a girlfriend to get her money back from another man. The footage seems to match the narration, but all the meaning is created in the editing. When stars are mentioned (Sue Lyon and Barbara Hershey both had romantic entanglements with Hampton), they are shown in archival footage of fiction scenes that most resemble Fancher’s impression of their charm.

Two of the most appealing titles, Raoul Ruiz: Contre l’ignorance fiction! by Alejandra Rojo and David Lynch – The Art Life by Jon Nguyen, Rick Barnes and Olivia Neergaard-Holm, are in retrospect also the more conventional. Relying on filling in the gaps in spectators’ knowledge of their filmmaker-idols and bringing abundant biographical information, they don’t go a very long way in actually deconstructing their art. Sure, it’s enjoyable to Ruiz fans to find out how he met consecutively with groups of scientists, poets and philosophers in trying to break new ground with his films. Equally, it’s amusing to hear, knowing Lynch turned out alright in the end, that his father told him he shouldn’t have any children after witnessing the dark abysses of his imagination. It fulfills our social curiosity to know more about the artists as human beings, hence the impulse to ask for their life stories and their views. However, if there is one thing that IFFR 2017 could prove, it’s that the films can often better speak for themselves.