Under the canopy of a star-dusted night, a circle of women farmers gather. The air hums with quiet whispers and anticipation, drawn by the promise of moving images reflected on a makeshift screen. Tonight, they watched Nirnay, (translates to “Decision”), a word steeped in both hope and burden. As the film unfolds, gasps escape lips, heads nod in shared understanding, and tears shimmer in the starlight. A farmer in the group sees her own stifled desires mirrored in the filmmaker’s journey. An elderly woman recognises the subtle shackles that bind her daughters, the weight of family honour etched on their foreheads. With each scene, the film becomes a mirror, reflecting not just faces, but the invisible burdens they carry. The final scene fades, leaving a silence as profound as the starlit sky. Yet, it’s not the silence of submission, but of contemplation. A farmer whose name I do not know speaks, her voice barely a whisper, “What if we could choose?” her eyes reflecting the flickering embers of the projector, and there, under the vastness of the night, a faint chorus begins. Not a song of despair, but of possibility.

“Kaun kehta hai jannat isse,

Humse pucho jo ghar mei fase,

Na ifazat na izzat mili,

Kar Kar qurbani hum mar gaye”

(translates to

Who calls this heaven,

ask us those who are trapped in home,

neither received protection nor respect,

we died making sacrifices)

Truth Is Merely Simple

While leaving the village, twenty hands sliced through the air, casting shadows in the fading light. Were they goodbyes, or silent screams erupting from hearts heavy with parting? Films, I knew, were powerful catalysts. Shared narratives could bridge the gap between individual struggles and collective awareness in search of truth. But answers, at this moment, were elusive. How do we interpret unvarnished truth in documentary filmmaking, especially when considering the pre-independence Indian era?Blumenberg, Richard M. ‘Documentary Films and the Problem of Truth’. Journal of the University Film Association, 29, 4, 19-22, F 77. “Film history, like every field, has its points of amnesia,” states film historian Stephen Bottomore.Battaglia, Giulia (2018) Documentary Film in India: An Anthropological History. London and New York, NY: Routledge.The history of documentary film in India is highly fragmented, consisting of multiple yet contradictory narratives with no ethnographic preservation. Documentary itself is a constructed reality, shaped by the filmmaker’s choices of what to record, how to frame it, and how to edit it. However, the act of pointing a camera at a subject inherently distorts the truth, as it creates a new perspective shaped by the interaction between the camera and the subject. The Lumière brothers’ iconic film Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station (1896) exemplifies this conundrum. The film captured a seemingly real-life event — a train pulling into a station. Speculations of staged scenes and pre-announced arrivals echo the ongoing complexities of non-fiction film, where every frame, from historical accounts to fly-on-the-wall observations, is crafted by the filmmaker’s hand, blurring the line between capturing and constructing a narrative. This very ambiguity fuels the genre’s brilliance, urging us to question how we define and engage with non-fiction on screen.

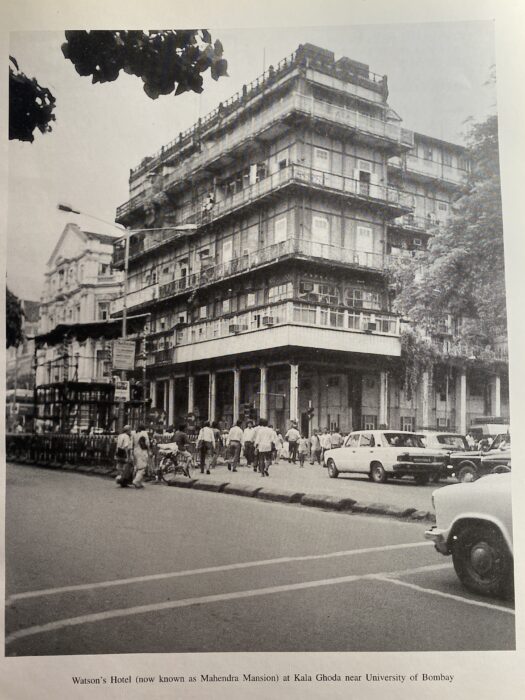

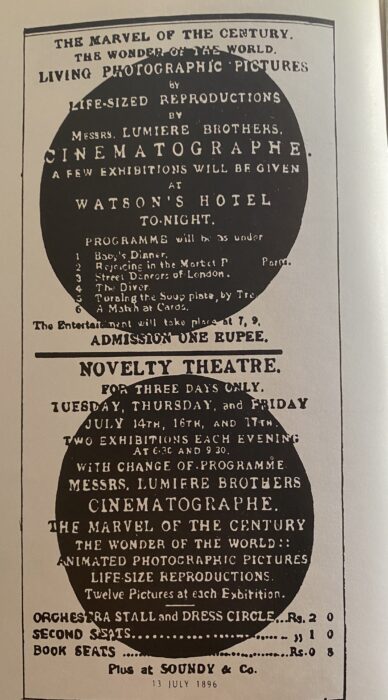

The emergence of film history in India was an almost synchronous occurrence, marked by the arrival of touring exhibitors who brought cinema packages to the audience in Calcutta approximately six months after the Lumière Brothers’ historic exhibition in Bombay in 1896.Rangoonwala, Firoze (1975) Seventy five years of Indian Cinema. India Library, N. Delhi.

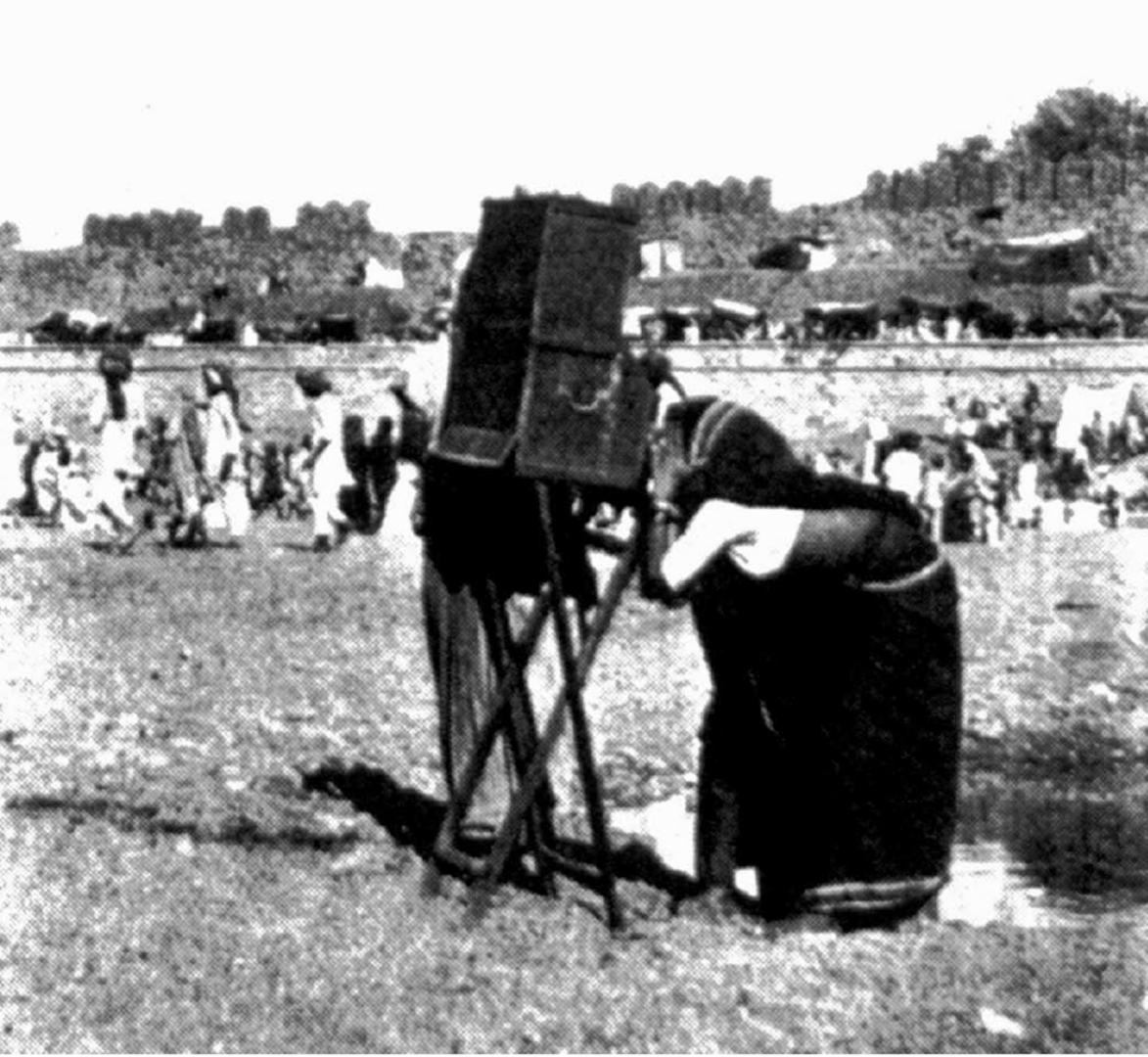

Long before the term “documentary” was coined by John Grierson, India was already exposed to various forms of moving images. Closely intertwined with the birth and growth of the cinema itself, the camera as a device made its way to India, a mere year after its introduction in the Western world. Before the arrival of celluloid film, entertainment forms such as peep-shows, panoramas, and magic lantern displays were attractions, showcasing elaborate scenes with lighting effects. These predecessors influenced early cinematic depictions, portraying battles, historical events, and natural landscapes—a tradition continuing in the visual language of film. The daguerreotype camera’s arrival in India in the 1840s sparked immense interest in capturing buildings, landscapes, and portraits. Early photographers like Samuel Bourne and Linnaeus Tripe documented India’s landscapes and people extensively. Their work not only familiarised the West with India’s visual culture but also laid the groundwork for visual storytelling, a crucial element of cinema. The Lumière brothers, pioneers of cinema, were heavily influenced by Étienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographic work, which used multiple cameras to capture sequential images. Faster photographic plates, shorter exposure times, and lighter, handheld cameras democratised photography, transforming it from a professional to a popular pursuit. Roll film and projector technology further revolutionised the scene. Strips of film could now be drawn through a machine, projected onto a screen at a steady rate, creating the illusion of continuous movement. By the mid-1890s, these ongoing attempts to film and project moving images culminated in the first short films being shown to paying audiences. When film technology finally arrived in the late 1890s, India already had a head start with its visual storytelling culture thanks to early photography and other cultural performances.

For instance, Dadasaheb Phalke’s silent film Raja Harishchandra (1913) used painted backdrops and innovative special effects techniques, showcasing the ingenuity of Indian filmmakers in shaping the medium. These early photographic endeavours were precursors to what would later become documentary filmmaking that included actualités, topicals, educational films, interest films, expedition films, and travelogues. Many films produced during the British Raj spanning from 1896 to 1947, predominantly revolved around themes of war and colonial propaganda.

The 1897 exhibition of the film of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession in London was a “major public event staged on a lavish and unprecedented scale”. This spectacle described the audience as actively and positively participating in the event. “It was fine to see how the pictured crowd waved hats, handkerchiefs and sticks, and how the audience responded to the demonstrations with hand-clapping and cheers when the Queen passed by”, wrote The Madras Times, in its September 1, 1897 edition.Hughes, S. P. (2010) ‘When Film Came to Madras’. BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies, 1(2), 147-168. Towards the end of 1898, cinema became a profitable venture, leading to the emergence of several exhibitors, both Indian and foreign. They operated in a variety of venues, including tents, sheds, and rented halls, utilising whatever film equipment they could find. Touring exhibitors offered mixed programs of European entertainment, effectively introducing India to what can be considered early forms of “documentary footage.” These programs often included Indian material shot by foreign operators, showcasing “exotic views of monuments, bazaars, religious processions and a few filmed theatre items”.Chabria, Suresh (2013) Light of Asia: Indian Silent Cinema, 1912-1934.

The Travelling Cinema: A Democratising Force

Long before the advent of multiplex chains, itinerant filmmakers, known as BioscopewallahsFor an example of the kind of films they made, see: A Native Street in India (1906), crisscrossed the Indian countryside, carrying their projectors and makeshift tents. The venues for early film exhibitions in colonial India, ranged from public halls to makeshift tent cinemas erected in playgrounds and maidans (open public spaces).Rangoonwala, Firoze (1979) A Pictorial History of Indian Cinema. Travelling exhibitors, often using horse-drawn carts or makeshift tents, transformed market squares and temple grounds into temporary theatres. This democratised access to the cinematic experience, allowing rural communities to engage with narratives beyond their immediate realities. The shows ventured beyond their initial locations and reached the other two major cities of colonial India: Calcutta in the east and Madras in the south. Due to the limited number of cinema theatres, many exhibitors travelled around the country organising ‘performances’ and pushed a new paradigm of cinema viewing: travelling cinema in small towns and rural spaces. Madras is reputed to have had its first permanent cinema house as early as 1900. But perhaps more significant was the impact of the travelling cinemas which toured over the entire region bringing foreign and Indian films to early filmgoers. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed the rise of India’s equivalent of the “travelling picture showman.” These early film exhibitors journeyed from city to city and ventured into remote rural areas, where access to cinema was a novelty. They followed in the footsteps of theatre companies that were also touring during this period, presenting popular theatrical forms and folk theatre performances.

While the initial embrace of cinema from India’s early political leaders immediately post-independence was tepid, with Mahatma GandhiAmateur footage of Gandhi in 1929 (Courtesy: British Film Institute)‘s outright aversion and Jawaharlal Nehru’s conditional acceptance of the visual medium for educational purposes, a remarkable phenomenon unfolded. Cinema not only adopted the language of nationalism; it seamlessly melded with its very essence, becoming an inseparable extension of the movement. Indian filmmakers like Dadasaheb Phalke were invested in consciously reclaiming tradition and history in order to instil in viewers the very sense of pride that Indian nationalist movements were attempting to kindleSengupta, Aparajita (2011) NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA. Early Indian filmmakers, in reclaiming traditional and historical texts, launched a subtle cinematic counter-offensive against colonialism. Their strategies mirrored the anti-colonial movements of the time, weaving narratives resonating with both heritage and resistance. Audiences, far from passive viewers, readily interpreted these epics as national allegories. Phalke’s silent mythological film Kalia Mardan exemplifies this — where viewers erupted in patriotic chants of “Vande Mataram” (I bow to you, Motherland) when the child Krishna vanquishes the evil serpent. This act of interpretation, fueled by the filmmaker’s subtle framing and the audience’s active engagement, transformed mythological narratives into potent anti-colonial anthems, blurring the lines between fiction and the yearning for national liberation. This wasn’t just about entertainment; it was about spreading narratives, weaving visual threads of defiance across a fragmented nation.

Jamshedji Madan, a theatre maven ventured into bioscope shows as early as 1902. His empire, Madan Theatres, soon transcended mere exhibition, blossoming into a production and distribution behemoth across British India. Responding to the burgeoning nationalist sentiment, the company launched its swadeshi (national) film initiative with a stark portrayal of the Great Bengal Partition Movement (division of the Bengal Presidency into two parts: East Bengal, now part of Bangladesh and West Bengal, which remains part of India), thus lending a visual voice to the era’s political unrest.Rangoonwala, Firoze (1975) Seventy five years of Indian Cinema. India Library, N. Delhi. While Madan planted roots, Abdulally Esoofally of Bombay became the wind beneath cinema’s wings. His travelling cinema wasn’t just a caravan of carts and tents; it was a mobile pulpit, carrying tales of resistance and cultural pride to the remotest corners of the land. Before establishing his travelling cinema shows in India, he toured Southeast Asia, honing his skills in the film exhibition business. Esoofally’s setup included a projector, a folding screen, a tent, and a staff of twenty five well-trained workers. Supported by four sturdy pillars, these tents were impressive structures, measuring 100 feet in length and 50 feet in width; it could accommodate more than a thousand spectators at each show. His partnership with Ardeshir Irani culminated in the iconic Majestic Cinema, where India’s first talkie, Alam Ara (1931), would be screened later. This wasn’t just a brick-and-mortar structure; it was a testament to the evolving infrastructure of dissent, a platform where the whispers of nationalism would soon explode into the roar of an independent nation. Examining the evolution of film genres in India reveals a clear connection between the nationalistic themes prevalent in Indian cinema and their emergence as a response to the established colonial discourse.

But this wasn’t a one-way street. The audiences weren’t simply passive consumers of images. They actively engaged with the films, their murmurs weaving a counter-narrative alongside the projected one. They cheered for freedom fighters, jeered at colonial oppressors, and added their own stories to the film’s tapestry. Milton Singer would call this a “cultural performance”, a dynamic interplay between the film and the audience, where meaning is co-created in the heat of the moment, transforming mundane spaces into theatrical spaces of screening.Battaglia, Giulia (2018) Documentary Film in India: An Anthropological History. London and New York, NY: Routledge. In the context of Indian documentaries, circulation of cultural material are invitations to a shared stage, where viewers shed their roles as spectators and become actors in the drama of social change. Bruijn and Busch argue that the circulation of cultural material, particularly through itinerant practices, serves as ‘an engine of conceptual change.’ This prompts ‘artists, poets, and religious practitioners’ to transcend their customary approaches. Contextualising this in the pre-independence era, exposure to new people and places not only influences them but also reshapes the meaning of cultural products implying a broader sense of evolution in both the content and reception of cinema. Lacking lasting institutional or material traces, there is little known information about the aesthetics of non-fiction but nevertheless colonial narratives, often steeped in stereotypes and subjugation, could be reinterpreted through the lens of resistance. Historical epics reframed as tales of defiance, mythological figures transformed into symbols of national identity, and even seemingly innocuous social dramas may have subtly challenged the status quo.

The dominant gaze of British filmmakers was often one of curiosity and fascination mixed with underlying assumptions of superiority. They might focus on poverty, “primitive” practices, or stark contrasts between British modernity and Indian tradition. Grand events, religious ceremonies, and architectural marvels received prominent attention, often romanticised to cater to Western audiences. Employing static shots, long takes, and minimal editing, the focus was on capturing life “as is,” showcasing India as an exotic and unfamiliar land. While pre-cinematic elements are significant, showcasing a stylistic connection with traditional art forms like shadow puppetry and narrative religious paintings, early films in India, influenced by cinematic techniques of the British, often employed static and frontal camera angles, presenting subjects with little visual dynamism. Lacking sound technology, early films screened resorted to live accompaniment, with bands stationed before the screen, filling the silence with song and, at times, explanatory speeches. Bridging the gulf between silence and story, Indian cinemas transformed into a communal spectacle. Live bands pulsated on makeshift stages, their music and spoken word dancing with the shadows on the screen, drawing the audience into an immersive dance of understanding and emotion.

Emergence of Indian Documentary Filmmakers

Short actuality films, known as topicals, flourished in the early decades of the twentieth century. These films captured real-life events and are considered predecessors to the Indian documentary film as a distinct genre. Some point towards footage of the ghats of BenaresSee here. (erroneously named as the Panorama of Calcutta in the archives due to lack of systematic labelling practices or due to the frequent use of the term panorama during those times to define landscapes) being the first actuality film shot in India, but it’s very difficult to trace due to lack of systematic records.

Meanwhile, the ‘educational and public utility’ category, akin to today’s documentaries, encompassed diverse subjects like travel, health, agriculture, cooperation, and cottage industries, extending beyond informational content. Establishing the cinema’s relation with the rising tide of Indian nationalism, in December 1901, Harishchandra S. Bhatvadekar made what might be considered the “first Indian newsreel.” It documented the public reception given to Indian student Ragunath P Paranjpye, who had achieved a special distinction in mathematics and returned to India after his studies at Cambridge. This newsreel marked an early example of how cinema could be used to convey significant events to the public.

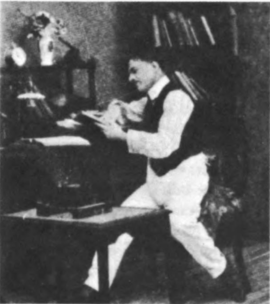

While film exhibitions were making strides, notable figures emerged in the realm of documentary filmmaking. Phalke, renowned for making India’s first feature film, also dabbled in “topical short films.” After importing a camera from England, Phalke embarked on an unusual documentary venture. To sway potential financiers for his mythological films, he created a short film titled Growth of a Pea Plant (1911) using the single-frame exposure technique. He planted a pea in an earthenware pot and meticulously recorded its growth over one and a half months. The result was what filmmakers, film critics, and scholars still consider the first Indian documentaryAshish Rajadhyaksha, Paul Willemen (2014) Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema. Routledge. By focusing on mundane subjects like plant growth and using time-lapse cinematic technique, Phalke may have subtly challenged the dominant narratives of the time, which often centred around mythology, religion, and exoticism, even though he later incorporated these elements in his fiction films.

His dedication to documentary filmmaking extended further when he created a documentary titled Chitrapat Kase Taya Kartat (How Films are Made) in 1917. In this film, he showcased the process of directing a cast, shooting scenes, and editing film topicals. It reveals a dual nature: pedagogical explanations of cinematic technology alongside his renowned mythological and religious films with special effects. His transparency empowers viewers by demystifying the filmmaking process and showcasing it as accessible, not just a product of elite expertise. This can encourage the audience to engage with film on a deeper level, fostering curiosity and potentially even inspiring amateur filmmaking ventures — the act of questioning what deserves cinematic attention might have subtly empowered them to think critically about the narratives presented to them and become active participants in shaping the cultural landscape.

In Calcutta, Hiralal Sen embarked on a similar journey, capturing scenes of Indian subjects and recording political events and advertisements. He documented scenes from daily life in Calcutta, including scenes on the streets, bathers in the river Hooghly, and even cockfights. During this filmmakers were actively engaged in both the creation and exhibition of films, and these two activities were deeply intertwined. Despite this symbiotic relationship, prevailing narratives in Indian cinema, particularly those concerning documentary filmmaking, have primarily emphasised the works of these individuals as filmmakers rather than delving into their equally significant roles as film exhibitors.

The Rise of Political Films and Censorship Practices

Separating politics from non-fiction is like trying to extract water from the ocean — it is simply inseparable. Real life is inherently political, woven through with power dynamics, social structures, and the voices of those silenced or amplified. Even the seemingly innocuous sight of a train arriving on a platform holds political implications. Who built the platform? Whose lives are intersected by its arrival? Does its presence signify progress or exploitation? Similarly, the person documenting it doesn’t merely capture a scene; he frames it, amplifies certain voices, and potentially excludes others. His perspective, shaped by privilege or marginalisation, becomes a political act in itself. Early film history often categorises films as actualities or topicals, which could encompass both everyday events and those with political undertones. However, defining what constitutes a “political film” from this era is challenging. Many early films, especially those considered political, were censored, lost, or deliberately destroyed by colonial authorities. The connection between political films and the birth of documentary as a discourse remains elusive due to the absence of concrete evidence, but it doesn’t negate the potential influence of political films on the evolution of documentary filmmaking. The use of real-time footage, capturing historical events, and subtle critiques of power structures all resonate with today’s documentarian practices.

As India’s struggle for independence gained momentum, filmmakers like Jyotish Sarkar turned their cameras towards capturing the pivotal moments of the independence movement. He documented the anti-partition demonstration in Calcutta led by Sir Surendranath Banerjea titled Surrender Not (considered the first political documentary film in India), the devastating effects of natural disasters like floods and famines, and the inspiring activities of Mahatma GandhiSee for a later example, shot by Kanu Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi Noa Khali March (1947) (British Film Institute). The Great Bonfire of Foreign Cloth (1920) depicted Gandhi alongside other prominent leaders addressing a crowd of around 60,000 people. The film went on to capture the burning of British cloth, symbolising a rejection of foreign influence and a call for self-reliance. Despite repressive measures by the British government, prominent film companies like Madan, Aurora, and Imperial sent their crews to document critical national events. These included the Congress sessions, Gandhi’s activities, protest marches, and arrests. These films weren’t merely passive documentation; they were actively used to mobilise public opinion and garner support for the independence movement. The arrival of sound, however, dramatically amplified the impact of documentary film as a political weapon. Capturing the raw chaos of protests, or showcasing Indians marching with banners in both Hindi and English, their voices echoing demands for boycotts ignited emotions and potentially swayed opinions in ways silent imagery never could. The colonial government needed a propaganda offensive, wielded through both printed press and, especially, the burgeoning power of cinema.

The British government saw political rallies as a direct threat to their authority. Gatherings of people voicing dissent, advocating for freedom, or criticising colonial policies could potentially spark unrest and ignite movements for independence. The act of collective action and public display of dissent was deemed more volatile than the relatively passive activity of watching a film. Additionally, the controlled and enclosed environment of a cinema hall made monitoring and potential intervention easier than managing large, open-air rallies. The contrasting treatment of film gatherings and political rallies in colonial India reveals the state’s anxieties about dissent, its strategies of control, and its perception of different social classes as posing varying degrees of threat. While film could offer subversive potential, it remained within a controlled sphere compared to the perceived volatility of open political gatherings. The rise of “bioscopes” and alternative screening spaces outside official control made it harder for the authorities to enforce censorship, allowing subversive narratives to reach audiences in remote corners of the country.

In 1927, the Indian Cinematograph Act Report was authored by a committee appointed by the British Indian government. This committee was tasked with examining and making recommendations related to censorship, film production, and exhibition practices across the country. The report shed light on the complex relationship between cinema and governance during the colonial period. The British government’s actions in confiscating and controlling the narrative through film censorship demonstrate the extent to which cinema was seen as a powerful discourse for shaping public opinion. On one hand, with the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, war propaganda films served as instruments for rallying support for the British war effort while on the other hand, non fiction cinema, in its nascent stages, found itself grappling with a potent mix of grief and national consciousness, capturing the iconic moments of political leaders. One may consider the example of the historic Dandi March in 1930, led by Mahatma Gandhi; unfortunately, the only images of this event and the subsequent police crackdown that survived were those captured by American newsreel companies. These companies managed to smuggle out footage of the Dandi March and released it in theatres in America. American newsreel companies saw greater commercial value in covering Gandhi compared to domestic events. The international appeal of Gandhi’s non-violent resistance and the exotic imagery of India attracted audiences in the West. With limited resources and preservation infrastructure, any Indian footage that existed might have simply deteriorated over time or been neglected due to the focus on Western versions of the event. The news of Gandhi’s assassination in 1948 plunged the nation into mourning. His five-mile funeral procession, followed by over half a million people, was a testament to his stature and the unifying power of his message was captured with the surging crowd breaking through police cordons, and the final pyre. Funerals, once private moments of grief, became public spectacles, their images and emotions amplified on screen, stirring national consciousness and forging collective identities.

The aesthetic of post-colonial Indian documentaries especially in the contemporary times wasn’t simply an extension of the past or a reaction to the present. They were a dynamic blend of pre-independence legacies, post-colonial realities, and international influences, resulting in a unique cinematic language that challenged established norms, amplified critical voices, and documented the socio-political struggles of a nation still finding its own voice since 1947. Dissatisfied with the post-independence reality, the 1970s saw the rise of independent documentaries, fuelled by a need for critical voices. Breaking free from conventional narratives, filmmakers experimented with non-chronological structures, juxtapositions, and subjective perspectives, reflecting the complexity of social realities and challenging viewers to actively engage with the content. While the colonial legacy need not define our cultural landscape, yet we often see a chilling reflection in our times. The state, steeped in the hangover of imperial control, sought to sculpt reality through censorship; this nascent form wielded a subversive lens. The response was predictable- Films were banned, confiscated, labelled anti-national. The silencing of critical voices of students, the systematic dismantling of cultural institutions, the use of draconian laws to arrest and detain activists and journalists; misinformation wielded as a weapon against dissent targeting minorities and any citizen going against the ideologies of the ruling state. But history has taught us this — when narratives are controlled, resistance will find its voice. My experience with the farmers is proof of this. In their hushed discussions, their questioning eyes, reflecting their own struggles, “What if we could choose?” Like the travelling cinemas of yore, filmmakers adopted guerrilla tactics. Screenings became clandestine rituals, held in hushed whispers, whispers that grew into roaring chants when farmers defied corporate land grabs, or slum dwellers refused to be voiceless cogs in the economic machine. In that act lies the future of India’s cultural landscape — recognising our own agency through the use of documentary narratives, both as a filmmaker and a spectator.