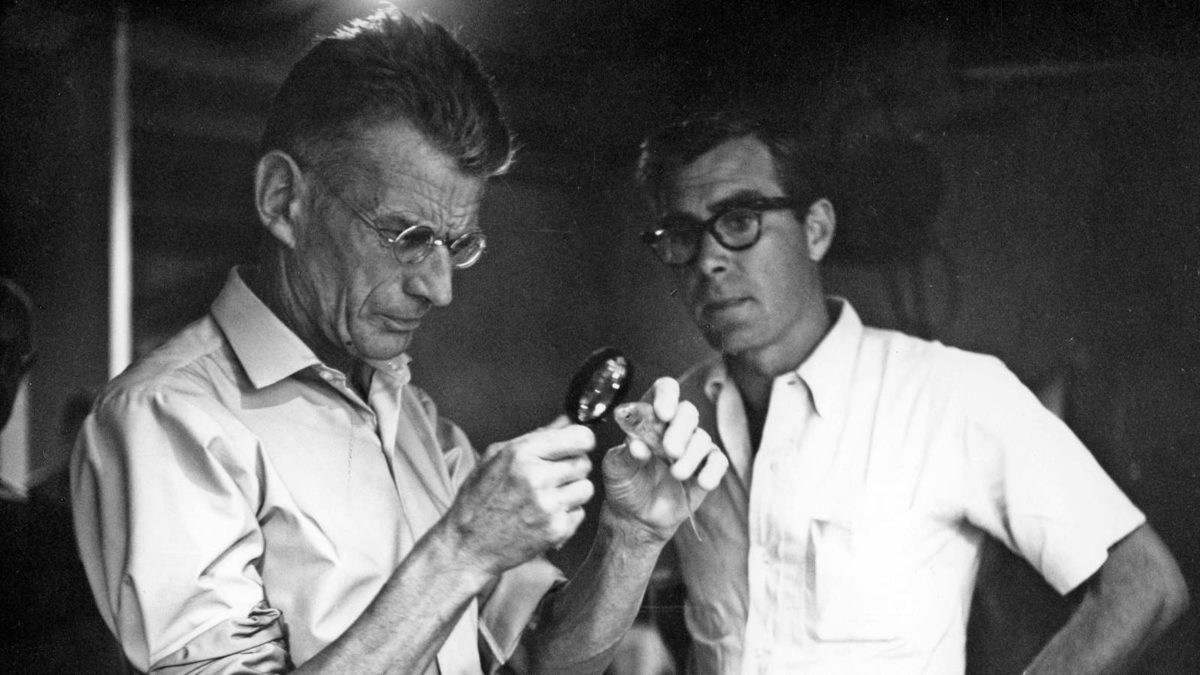

Although Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) showed a genuine interest in audio-visual media in his fascinating and innovative radio plays and television works, and in 1936 even wrote a letter to Sergei Eisenstein to be accepted to the famous Soviet film school VGIK, the 22-minute Film (1965) was his only venture into cinema. Beckett conceived the film, wrote the screenplay, supervised the production and, as one of the film’s crew members recalled and as the director Alan Schneider himself acknowledged, ‘Beckett directed the director’. Because the practice of filmmaking didn’t exactly turn out as the unexperienced Beckett had imagined, he considered the film to be a failure. The recent 4K restoration of Film by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, in cooperation with the British Film Institute, and the documentary/film essay NotFilm by UCLA restorer Ross Lipman, however, aim to bring Beckett’s Film back into the spotlight and stimulate a reappraisal of its remarkable qualities.

True to its explicitly self-reflexive title, Film opens with an extreme close-up of a human eye. The eye is closed, then it opens and blinks, immediately revealing the theme of the film: it will be about watching and being watched; in short, it will be about cinema. At the same time, the opening shot introduces one of the two main characters in the film, E, the eye, who is impersonated by the camera most of the time. The other main character is O, the object E is looking for (in the film these characters don’t have names, but they are designated as ‘E’ and ‘O’ in the screenplay). When the camera takes O’s point of view (mainly in the last part of the film), the image is distorted, making it easy to distinguish between E’s and O’s gaze.

After the opening close-up of the eye, the camera/E scans a brick wall and suddenly, as a human eye would do, shifts to O, a tall man wearing a long overcoat and a hat. O is anxiously running against the wall, trying to escape E’s look and thus trying to avoid a direct confrontation with the camera. As a result, we only see O from behind. The fact that Buster Keaton was cast in the role of O lends extra weight to this stylistic choice. Indeed, Keaton, the then-68-year-old slapstick grandmaster of the silent film era, is known as ‘the great stone face’, but his main characteristic, his stoic face expression, isn’t visible until the end of the film. This choice highlights the central importance of the gaze, and the attempt to escape it.

In this respect, it is illuminating to note that the Latin phrase esse est percipi (to be is to be perceived), upon which the 18th-century Irish philosopher George Berkeley reflected, was an epigraph for the screenplay. In an interview with film historian Kevin Brownlow, Beckett explained that ‘The man who desires to cease to be must cease to be perceived. If being is being perceived, to cease being is to cease to be perceived.’ In fact, the whole film can be seen as a reflection of this idea. And as watching and being watched are central concepts to the ontology of cinema, cinema offers the ideal medium for such a reflection.

Cinema, of course, is an audio-visual medium, but Beckett consciously chose to focus only on its visual dimension by doing away with the soundtrack altogether, with one exception at the beginning of the film. While O is running away from E, he bumps into a couple and quickly hurries further away to an apartment building. The man opens his mouth to shout something to O, but his wife holds her finger over her mouth and says ‘Shhh!’ This is the only bit of dialogue and even the only sound in the film. This is not only remarkable in light of Beckett’s oeuvre, but also reminds the audience there is the possibility of sound, but that sound is absent: the film is about the visual realm, which is underlined by the choice to maintain absolute silence. There is not even recorded silence; the soundtrack is simply absent, which has a strikingly alienating effect. It should be noted here that, although this is not immediately notable from the film itself, the screenplay reveals that Film is situated in 1929, during the transitional period from silent film to sound film.

When the man and woman make direct eye contact with E, the couple turns away in anxiety. O subsequently enters the staircase of a building, where he encounters an old lady carrying flowers. As E is distracted by this, O manages to pass E and to sneak into a room. It’s a typical Beckett room, bathing in austerity: grey, dirty walls, one window, one simple bed, a rocking chair and a mirror. There are also pets: a cat, a dog, a parrot and a goldfish. The problem with these animals is that they have eyes, meaning that they can look at O. Consequently, O tries to get rid of the animals, which results in the only slapstick scene of the film as each time O puts out the cat, the dog enters the room again, and vice versa. O further eliminates possible external looks by closing the window blinds, pulling a picture of an ancient god from the wall and tearing it into pieces to avoid the eye of God, and covering the mirror to exclude his own gaze.

Sitting in his rocking chair, O looks at old, somewhat unnatural-looking pictures displaying pivotal moments in his life: days of childhood, youth, graduation, marriage, the birth of a child … In these pictures, we finally see O’s face and in the last picture, we see that O is wearing an eye patch, emphasizing again the importance of the gaze and perhaps suggesting an explanation for O’s traumatic relation to it. Then he tears the pictures into pieces one by one, as if he wants to get rid of his past or his memories of that past. After eliminating all of the looks from others, he also erases his own inward look. The work seems to be done and he falls asleep. This, of course, gives E the opportunity to get closer to O and observe him. Having already seen pictures of O, we now see his face for the first time ‘in real life’. When the camera comes closer to O’s face, O suddenly awakens. He looks frightened at the camera, covers his eyes with his hands, looks again and covers them again. The screen turns black and the opening close-up of the eye reappears.

During the restoration process of Film, Ross Lipman, known for several other restorations of independent and avant-garde films, found a lot of original and rare material on the production of Film. At the same time, he was struck by the film itself and found it had not yet received the attention and appreciation it deserved. As a result, Lipman made the documentary/‘kino-essay’ (as he calls it) NotFilm with a twofold aim. On one hand, based upon archival research and interviews, NotFilm provides a rigorous reconstruction and analysis of the conception and production (and a little bit of the reception) of Film. This is state-of-the art film historiography and Lipman convincingly shows that film can be used very effectively as a medium to present original historical research.

The most exciting revelation of NotFilm is the rediscovery of the footage that was shot for the first scene of Film. This first scene would initially involve seven couples and would last for about eight minutes. When viewing the rushes, however, everybody was disappointed with the results and the scene was compressed into two minutes, keeping just one couple. This was the only scene in Film that fundamentally differed from the screenplay and the footage of the other couples was long thought to be lost. Lipman, however, rediscovered the takes in the film cans UCLA received from Barney Rosset, Beckett’s American publisher, who had commissioned Film. NotFilm is thus able to convey an impression of how Film’s first scene could have looked. Another unique revelation of the documentary is provided by audio recordings that Barney Rosset made during the production meetings at his house in Easthampton. On the recordings, we can hear Beckett (for Film, he made his only trip to the USA), director Alan Schneider and cinematographer Boris Kaufman, the youngest brother of Dziga Vertov, discussing the screenplay, the characters and the stylistic features of Film. As there are only a few minutes of audio and video recordings of Beckett, this is a major revelation indeed, providing a glimpse of Beckett’s creative process.

On the other hand, in addition to being a historiographical documentary, NotFilm is also an audiovisual essay about Film and its philosophical implications. This is already clear from the documentary’s opening words: ‘I never trusted films about film. Art should be about life. So I told myself. As if they were distinguishable.’ Lipman beautifully illustrates his reflections by means of fragments from the silent film era, most notably the American slapstick tradition of Chaplin and Keaton and the great avant-garde period of Soviet cinema (in which Beckett had a great interest), particularly the self-reflexive cinematic work of Dziga Vertov. Lipman regularly makes good or intriguing points, for example when he argues that Film is essentially a chase film, with E chasing O. At other times, however, Lipman seems to lose a bit too much nuance in his attempt to make strong statements, for example when he continues his reflection on the previous argument by stating that the chase film is in fact the essence of cinema, or when he argues that Beckett had found ‘his double’ in Keaton. One can easily disagree with some of the ideas Lipman puts forward, but then again, his arguments remain intriguing and open up the debate – exactly as an essay should do.

At most events, Film and NotFilm are shown as a pair, starting with Film. For a fuller experience, however, NotFilm should be followed by another screening of Film, as an audience would look at it with different eyes after seeing NotFilm. Indeed, this is NotFilm’s biggest achievement: it successfully forces you to actively engage with Film, thereby increasing the viewer’s appreciation for and consideration of Beckett’s unique contribution to cinema.