Scurrying toward the last seat at the sold-out screening of El futuro perfecto at Film Fest Gent – a full fifteen minutes late (in a film of only slightly more than one hour) and entirely unaware of what I am about to watch – I get the most curious of flashbacks to high school French class. As I drop my bag to the floor and get settled in, the disconnected tone of voice of who will turn out to be the protagonist matches up with the subtitles I’m finally starting to read. What I’m watching is reminiscent of the awkward videotapes and ‘everyday’ dialogues that are the favourite interactive learning material of every language teacher I’ve ever encountered. Director Nele Wohlatz – who happens to teach German – follows through on this stylistic choice, the result being an intriguing and intelligent personal history that will leave you at a loss for words – as opposed to its resourceful protagonist.

Nele Wohlatz, a German immigrant currently living in Argentina, demonstrated her preoccupation with migration and particularly with questions of identity and self-presentation in her co-directed first feature, Ricardo Bär (2013). With the semi-fictional El futuro perfecto, she looks into how immigrants have to translate themselves to another culture by following Xiaobin, a young Chinese woman trying to find her way around Buenos Aires. All but one of the movie’s characters are non-professional actors and its premise is based on a combination of Wohlatz’s and Xiaobin’s experiences. Wohlatz explained how she met Xiaobin Zhang through the language institute where she teaches and was inspired when she saw a theatre piece the students had to bring in their newly acquired Spanish. They were not acting or invested in the acting, yet it was engaging because you could see their own real life struggle (of simply trying to pronounce their lines) shine through the performance.

Language is the driving force behind the plot: as Xiaobin learns more of the Spanish vocabulary, she understands and articulates her world in more complicated terms. The film is not about the frustrations and difficulties that arise when speaking in a second language. It is about the use of a language to confront an increasingly complex reality with increasingly complex relations. Besides Wohlatz’s attention for the reinvention of the self through language acquisition, she also has an interest in the artifice of cinema, which was sparked by the problems she encountered while shooting Ricardo Bär. It was supposed to be a documentary film but ended up hovering between fiction and documentary and emphasizing the intervention of the filmmakers throughout.

Bressonian Influences in El Futuro Perfecto

In El futuro perfecto, Wohlatz explores her interest in filmic artifice by way of performance by pairing acting with language acquirement. The latter in fact becomes the inspiration for her own cinematic language. As she establishes in an interview with Mubi’s Notebook, “this is what interests [her] in filmmaking: you create a whole system in order to tell a story. The story, the topic influences the language for the film.” Xiaobin’s progress is translated most gradually and evidently through acting and language, while lighting, frame composition, costuming and other formal aspects continue along the same lines for most of the film. Many of the choices are reminiscent of the work of the French filmmaker Robert Bresson. As will become clear in the following paragraphs, the use of very simple backdrops and costumes, sober compositions and repetition in combination with the acting style seem heavily inspired by his work. On closer inspection, it appears as if Bresson’s legacy fostered a use of non-embellishment and non-naturalistic acting that became important to depictions of migration and alienation by other auteurs, such as Eugène Green and Straub-Huillet. These filmmakers – whom I will return to in due time – in turn, relate in various ways to Wohlatz’s work.

White Light, White Noise and Grey Surroundings

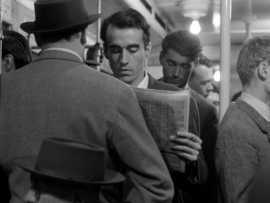

Xiaobin’s Buenos Aires is a blank space. Its walls are white, off-white or beige and in most cases lit by the cheap, cold light you associate with night shops. The choice of light is semi-realistic, as Xiaobin’s environment mainly consists of a classroom, a snack bar, the metro and the laundry service where her mother works – the kind of environment we’d generally associate with efficient fluorescent lighting. Then again, it becomes an abstraction because of its continuity: it seems to be the general impression Xiaobin has of Buenos Aires. Lighting sets the tone for her experience of her new habitat. She is bathed in a light that suggests many things: clinical objectivity, coldness, efficiency but certainly not hospitality. In fact, it exudes just the opposite, as the whiteness is reminiscent of places of transience that seem to urge you to move on. They are open to visitation but the brevity of the visit is implied.

The outside scenes are also decisively bland. As Xiaobin walks the streets, there is not a single colour that stands out. Facades have mild greyish tones and everyone is dressed to blend in. Wohlatz indicated that she chose to not make any adaptations to the colour in post-editing, opting instead to show the colours the way they naturally appeared as they filmed in 2K. The lack of saturation flattens the world. Especially in the park, where we expect vivid colours, the colour scheme becomes an unspoken restriction. The images show us the idea of a park, an abstracted park with no material presence. Xiaobin’s perception is one of cautious distance: instead of fully processing the vibrancy of the park, it is denied its status as a real space because participation is out of her reach. The static camerawork combined with the rather stoic actors, makes the park a space of stranded, congealed ton-sur-ton units. Bresson, although in a different manner, worked toward a representation of idea-places, for example creating the idea of a race track in Pickpocket (1959) by showing fragments of an agitated crowd and including the sound of galloping horses and announced winners, rather than opting for an establishing shot. Wohlatz’s camera has a similar way of refusing to wallow in atmospheric images of a location, preferring to efficiently illustrate with a minimum of signifiers.

To create his idea-places, Bresson thus relied on sound, which did not contribute to realism and immersion but rather worked in the same elemental manner as his other choices. The sound mix favoured certain signifying sounds over others to create a distilled ambience referring to a certain location. However, in his Notes sur le Cinématographe (1975), he also speaks of a so-called “silence obtained by a pianissimo of noises” (translated by Jonathan Griffin, p. 21) that seems to have crept into Wohlatz’s practice. In El futuro perfecto, white noise pervades every setting: all the sudden and overwhelming noises that you would realistically hear in a city like Buenos Aires are mixed until they become an alienating susurration, seemingly mimicking the buzzing of the out-dated electronic devices surrounding Xiaobin in her work and home environment. For the foreigner, the city’s constant murmur drones on without gaining in significance.

Elementary Compositions

Long takes of simple compositions create an austere setting for the events. Every environment is comprised of only the most essential signifiers. Instead of a characterization of space, establishing its relation to reality, there is a sparse functionality. The costuming is designed along the same lines. It is not an extreme minimalism, but the clothes are just unspecific enough to suggest a certain interchangeability. A similar approach can be found in Bresson’s Pickpocket, where Michel returns in an identical, unruffled suit scene after scene, even after tearing it in the previous one or re-appearing after several years abroad. Slightly more frivolous, but nonetheless effective is Xiaobin’s recurring white ‘kitten’ shirt and armour of profoundly inconspicuous clothes.

Rather than restful, the still emptiness is disconcerting and alienating. A shot that exemplifies this shows Xiaobin sitting on the stairs in the corner of the laundry service where her mother works. The left side of the frame shows a full rack of packed clean laundry, neatly stacked and numbered. Leaning against it, on the surface of the adjacent table, lies an organized cluster of hangers with an iron placed diagonally in front of it – at an angle at which the modest house-hold appliance somehow looks ostentatiously defiant. On the wall on the girl’s other side there’s a calendar. She is reading from her Spanish language book – which she seems to carry everywhere – while her mother complains to her off-screen. Xiaobin is supposedly not earning enough money to help her family, the plan after all being to make enough money in Buenos Aires to eventually have a comfortable life back in China. The mother walks across the screen a few times, always too close and as such, always out of focus. She seems to not actually materialize in the film because in her ‘perfect future’, she is not part of Buenos Aires. She is presented in the setting only vaguely, no more than a ghost in Argentina because she refuses to place herself in that reality, a standpoint also apparent from her refusal to learn the language.

Also reminiscent of Bresson’s work is the way repetitions of and variations on elementary actions make up the body of the film. Xiaobin, being an immigrant and living in a strict family, resides in a world consisting of essentials: a place to eat, a place to sleep, a place to learn, a place to work. The actions of entering, inhabiting and leaving of these places recur frequently in the film because these experiences are in themselves challenging. Variation cues the evolution of the plot: at first Xiaobin goes to a restaurant and can’t order anything because she speaks no Spanish, the next time she goes, she’s with her date Vijay (Saroj Kumar Malik, an Indian immigrant) and they order an orange juice. It is a narrative of repetition and learning through repetition in every way: learning to inhabit a place as you learn to inhabit a language. It is also interesting to note that we never get to see the inside of her parental home, only the sombre façade. The only proper meal she has throughout the film (she usually eats street food like sandwiches or hotdogs, and at some point cereal out of her purse) is at Vijay’s apartment, suggesting how much more of a home it is to her.

Language Learning and Acting Style

The dialogue and acting style are inspired by the awkward generic sentences used to teach people how to make conversation in language acquisition books and courses. The uniform manner in which the characters deliver lines in the sketches they have to perform at school and the way they speak Spanish in everyday situations aligns with the sense of alienation and the lack of comfort that comes with speaking another language. The Spanish that will become a second skin is at first ill-fitting and inconvenient. The conversations they sustain are conducted in a matter-of-fact tone, resembling the way you’d ordinarily repeat a line in a foreign language you’d just been taught.

Throughout, there is no vast difference between the way the students talk in Spanish class and the way they interact in their everyday lives. The lines in El futuro perfecto are pronounced, not performed; not acted, but said. The movements are executed in a Bressonian mode: agile, not artful (Notes, p. 19). Like the décor, they only comprise the strictly necessary. When Xiaobin has to wait for her sister outside her apartment building, she simply steps outside, halts and remains there, motionless, until her sister comes to stand beside her. Movements and words are not exactly performed with detachment, rather conveying an unavoidable isolation. The Spanish language students have to say the words without them stemming from their own mind or being in any way part of them. The acquired language does not come from within and, as such, a barrier is formed around the person. The message has to somehow permeate that barrier, a process that runs parallel with the increasing proficiency of the characters. The sentences they acquire during the first few Spanish classes seem completely at odds with the language learners’ reality – none of the stranded Chinese youths can identify with or knows a “Susanna who is a medical doctor.” Toward the end of the film, however, the acquired dialogue always has some link to their reality. The language learners are no longer outsiders to the language and culture; they have their own world to express. When Xiaobin learns the conditional tense, the example sentences are all in the strand of “I would like to live alone, without my parents.” So Xiaobin is playing her role in saying them, while they palpably resonate with her reality. There is a congruence between what she says and who she is (as a character).

Eugène Green: Space and Language Structure Life

Another body of work that resonates with El futuro perfecto, is that of Eugène Green. Besides the opening shot of open water shared with Green’s La Sapienza (2014), Wohlatz’s feature takes many more cues from the, American émigré, who’s work in turn was inspired by Bresson, especially stylistically. Attention for language is a common denominator for Green’s films, as is the non-naturalistic declamatory acting style, derivative of the Baroque theatre he puts on with his French theatre group Theatre de la Sapience. Many of his films attest to a preoccupation with foreignness and alienation.

Especially La Sapienza, with its central theme of longing for a sense of home, is exemplary of this tendency. This despite the fact that the theme is not made explicit until the end, when Green’s cameo as a war refugee narrates how “all of our misfortune comes from being refused a place where we could receive the light of God and love our fellow man.” Sappy, perhaps, yet the film in its entirety demonstrates a neat balance in which attention for the structure of everyday life is expressed in the simplest of terms. As friendship builds between the French couple central to the film, sociologist Aliénor and architect Alexandre, and two young Italian siblings they encounter, Lavinia and Goffredo, the newly formed duos each take on another language. Aliénor and Lavinia go on to speak French, a language the young girl is studying, even though she questions why exactly it has so many rules. Alexandre and Goffredo, a young architecture student, go on to speak Italian. Architecture and language are measured and re-measured in search of their essence: their effect on human life.

The link between architecture and language becomes clear during a tedious dinner Alexandre and Goffredo attend at the De Medici residence where André, a friend of Alexandre’s, is giving them a tour. When Alexandre asks his friend, another architect, what he’s been up to, the latter expands on an archaeological project where he’s been helping out. At a site near Lazio, some Etruscan relics were found which André helped puzzle together. The archaeologist he assisted needed his help discovering the meaning of an engraved stone they found in the ruins. The only three words they were able to decipher being ‘dawn’, ‘treasure’ and ‘sapience’, the archaeologist came to the conclusion that the stone says “the treasure of dawn is sapience.” The reconstructed sentence echoes the dynamic between Goffredo and Alexandre, with the young architect helps the master to regain attention for the simple truths of life, truths Alexandre recaptures in his effort to speak Italian with his protégée.

Although the parallels between space and language and their importance for human life are a concern throughout – Aliénor’s occupation as a sociologist introduces the problem of migration in a very early stage of the film – they find their most eloquent expression during Green’s cameo. Introducing himself as a Chaldean to Aliénor – who’s first reaction is, “isn’t your people extinct?” – he laments the loss of his world, but foremost his language. ‘Chaldean’ was the Hellenistic designation for the inhabitants of a part of southeast Babylonia between the 9th and 6th centuries BC that was famous for its oracles, which of course is the role Green takes on in Aliénor’s story. (Note the way a historic figure appears and interacts with present day reality, a nod toward our next author duo, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet.) Once, the Chaldean had a dream of living in his native Iraq and speaking his own language with his children, with a French radio station on in the background. Yet now, having lost some of his children, and with the remaining two living abroad in America and France, his only future is to find his way to his daughter in Paris and die there, as a man bereft of his language and his faith. Language is living space and living space is language, both conjure up a human life; a network of relationships.

Absence as Opportunity

In contrast to La Sapienza, the logic of homelessness in El futuro perfecto is born from absence to a much higher degree: from the things that cannot be said, the home that is not, the things that cannot be seen nor articulated. The Chaldean’s monologue in La Sapienza muses on home, on the things that make up a home, and even goes as far as defining it – recall the account on light, love and God introduced earlier. Eugène Green’s language is simple, and does not pretend to cover the full spectrum of the things discussed, well aware of the deficiencies inherent to any presentation. The shortcoming is even commented on earlier, when Aliénor discusses the fate of migrant children, emphasizing that “the statistics cannot convey their misery.” In its simplicity, the language of Green brings to mind more of a reality than any degree of verisimilitude could, and such is the strength of his artistic concept. Yet, rather than choosing this form of simplified demonstration, El futuro perfecto opts to speak through absence, the non-construction of things. The absence of home suggests homelessness and the absence of colour an absence of life. Stylistically, the film articulates the obligation to stay outside of things. In La Sapienza all such tragedies are put into language, everything can be articulated to some degree.

Take as an example the way Xiaobin’s house is portrayed. Any time she enters it, the camera shows her going inside in an extreme long shot, followed by a slow tilt upwards, as we imagine her going up the stairs. The only view of her living environment we get is the façade of her building. The absence of the interior space, which is never entered or narrated – as opposed to Alexandre and Aliénor’s house-that-is-no-longer-a-home or the home lost in war the Chaldean speaks of, in La Sapienza – suggests the non-existence of the home. Like Xiaobin’s mother, who’s only visible out of focus, the home is not really there.

Language is treated differently according to the same logic. There is, especially at the beginning of El futuro perfecto, a strong emphasis on absence of comprehension. The simple language of La Sapienza signifies just that: simplicity, whereas the restricted vocabulary of Xiaobin refers to a lack of understanding that is almost constant, only broken through in short moments of communication where her basic language can grasp some part of reality. Xiaobin has to start off her relationship with Vijay communicating only in Spanish class catchphrases, often not understanding his answers in the progress – imagine trying to explain you’re a computer programmer to someone who still has a hard time ordering orange juice in the only common language you’re forced to share.

In either case, the absence in El futuro perfecto is a way of communicating possibility. What cannot be expressed at the start of the film becomes articulated toward the end. As such, a future starts to become reality and every remaining lack becomes a measure of future possibilities. Although Green – in an interview with Film Quarterly (vol. 68, no. 4, 2015) – has expressed that “what’s most important can be represented most strongly and most efficiently if you manage to make the spectator feel the presence through the absence,” Wohlatz seems to have taken his notion of absence and given it a new meaning – one less mystical and more structural.

Both Wohlatz and Green seem to depart from the idea that ‘man exists through language,’ or in other words, that language construes identity. Green testifies to having found himself in the French language, experiencing the platonic ‘impression of remembering’ during the learning process. He, in other words, believes language to have the possibility of closely resembling a fatherland. Another pair of filmmakers that shared that background of expatriation and developed their art practice along the lines of those experiences, were Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet. They took a palpably more politically inclined approach to the matter of language.

Straub-Huillet: Language, Foreignness and Power

The French filmmaking duo Straub-Huillet used a radical formal approach to address socio-political issues. Their formal attention to language stems from the way they experienced their own foreignness as migrants in the countries where they undertook most of their work: Germany and Italy. The forceful way in which Straub was to acquire German as a young boy may have instigated the way the duo linked language use to power relations. Wohlatz indicated in an interview that she chose to make a film about Xiaobin’s language acquisition process because she had a similar way of understanding Argentinian reality.

As in the work of Straub-Huillet, for example in Klassenverhältnisse (Class Relations, 1984), complex existential problems are broken down into elementary language. When asked why he works during the day and studies at night, a young man answers, “there is no other way. I have studied all the options and this way of life is the best one.” The declarative tone of voice and simple conversation discusses reality in its most basic terms. Similarly, when asked whether she wouldn’t like to have a cat, Xiaobin simply answers that she does not want to take care of anything, as she already has to take care of herself. Vast questions about financial security and creating a home are reduced to elementary choices: day job or no day job, cat or no cat.

Straub-Huillet’s Sicilia! (1999) extensively pays attention to the musicality of the Sicilian dialect as spoken by the native speaker and non-actor playing the mother (Angela Nugara). Nugara becomes an embodiment of the language, the exact opposite of Xiaobin. The musicality of the language mother and son are loudly communicating in from opposite sides of a door, becomes more poignant than the subject they are discussing. As Straub and Huillet are French and working with Italians, they seem to have a particular, distanced awareness of the language’s musicality. They understand it, but they hear it as foreigners, with due distance from the natural understanding of the language. Their interpretation will never coincide with that of a native Italian speaker. Furthermore, Straub-Huillet’s way of letting ordinary people declaim canonical pieces by Franz Kafka (Amerika, 1927) and Elio Vittorini (Conversazione in Sicilia, 1941) in Class Relations and Sicilia! respectively, finds an echo in the way Wohlatz’s Spanish language learners mindlessly repeat the sentences about doctors and nurses without exhibiting any relation to the content.

In El futuro perfecto, however, a progressive embodiment occurs as Xiaobin makes the language her own. At first, every Spanish sentence she says sounds detached and the only time the characters’ voices are inflected is when they are speaking in their mother tongue. Dialogue and acting style are aligned: as long as the only statements Xiaobin can make are elemental, her acting consequentially leans toward minimalism. A tension is created through the juxtaposition of the natural, embodied Chinese and the artificial Spanish. Yet, by the end of the film, as she gets more of a grip on her conjugations and starts speaking rather fluently, her Spanish starts to sound more inflected or embodied.

The distance the immigrant experiences from his new reality as depicted in El Futuro Perfecto shows many parallels with the work of Straub-Huillet, notably in the way language determines power relations. Gaining proficiency in Spanish, Xiaobin gains agency. Any time she learns a new expression, her world expands and she becomes a more capable individual. The inequality becomes clear in the first scene, when Xiaobin, in close-up, barely comfortable saying short phrases like ‘my mother, my father and my sister’, has to answer rather extensive questions her off-screen Spanish language teacher is posing her. The teacher remains an intimidating presence, escaping all scrutiny as she consistently remains in the off-screen space, while taking on a rather condescending tone.

Xiaobin is determined to learn Spanish and build a life in Argentina in order to escape the strict family life and class immobility to which she’s otherwise convicted. The logic of absence as opportunity gives her the option to live a life beyond what she thought possible, as becomes clear when she’s asked to use the conditional tense to conjure up possible futures in her class. Proficiency equals agency.

With Straub-Huillet, Wohlatz shares an additional interest in the boundary and link between artifice and authenticity in film. The former are known for not manipulating the image in post-production in order to stay as close to a depiction of reality as possible, similar to Wohlatz’s decision to leave the low saturation of the 2K digital material in its original state. Another key practice that the duo and Wohlatz have in common is the juxtaposition of non-actors with actors and different acting styles. This is seen in Straub-Huillet’s work in in Class Relations (among other examples), where the performance of Mario Adorf stands in stark contrast to that of the non-actors. In El futuro perfecto, the only professional actor (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart) is not mentioned in the closing credits, as opposed to the non-professionals.

Acting seems to be defined as a language on its own. The sole professional actor appears sitting on a patch of grass with one of the Spanish language students, who is teaching him some phrases in Chinese. Biscayart says in Chinese that he’s an actor, proceeds to sum up the languages he can speak and then ends with “and now I’m pretending that I can speak Chinese.” In the conversation that ensues, the young Chinese man sitting next to him congratulates him, saying that it does not sound like he’s acting at all, to which the actor replies: “But I am, just like you are.” When he speaks Chinese, even as he’s learning, he does so casually. He asks about the weather with a natural inflection. He acts in a more naturalistic register. As the scene proceeds, the Argentinian actor returns to his native Spanish and one of Xiaobin’s fellow students asks him to teach them how to act. He teaches them some tricks to cry on command.

The scene depicts power shifts related to the level of proficiency people display in a certain discipline. When Biscayart speaks Chinese, he is a student, yet when they’re acting, he’s the mentor. As an actor, he can more efficiently present himself in front of the camera. He has the ability to make the most of the opportunities offered to him because he has a better understanding of that mode of self-presentation. As he candidly points out, when you are speaking another language, you become another person. Language is self-presentation, but it is also coming into a new self through acquirement, shifting from self-presentation to self-articulation. The process of acquirement promotes self-articulation throughout El futuro perfecto, yet Biscayart stands outside of this process as he is ‘acting’ that he can speak Chinese, and acting is a language he already mastered. This distinction might be the reason he is excluded from the credits.

Artifice or Authenticity, Actor or Bressonian Model?

Questions about authenticity and artifice, with respect to the preference for non-actors, surface in the scene with Biscayart. The motivations to opt for non-professional actors and a non-naturalistic acting style run far and broad and can be influenced by any number of predecessors. Bresson’s Notes sur le Cinématographe and body of work, however, seem especially interesting to study while looking into Wohlatz’s work. Both Green and Straub-Huillet relate to Bresson in various respects. The central idea is that non-naturalism makes for authenticity; psychological interpretation and acting technique always suggest artifice. An efficient, minimal script helps to obtain authenticity from the actor (professional or non-professional). In the aforementioned interview with Film Quarterly, Green stated:

What interests me is to capture what’s hidden in reality and to make it visible or perceptible. When I film a person, it’s the interior energy that interests me. (…) The words liberate an energy.

The simple dialogue and detached manner of speech as a means to arrive at an inner truth are cues Green took from Bresson, although the latter was perhaps more radical in his approach, never working with professional actors, as they have tricks up their sleeve to shape a performance. Bresson deliberately discarded his non-professional ‘models’ after they had contributed to one of his films, preferring them to never appear in any other feature because they would have lost their unaffectedness and become actors after watching themselves on the silver screen. Wohlatz chose Xiaobin Zhang to depict herself and her own struggle, and the register in which she acts at the beginning of the film, strongly resembles the non-acting of Bresson’s models.

Bresson, in his Notes (p. 7), jotted down what became an entire list of rules for his cinematography, but perhaps most central to all of it was the distinction between

BEING (models) instead of SEEMING (actors).

According to Bresson, this distinction and the unique realness of each model were what made ‘cinematography’ rise above ‘cinema’. The being of the model brought authenticity. Instead of simply adopting this logic, Wohlatz seems to have reversed it. Fair enough, at the beginning, Xiaobin resembles the model. As she cites language she does not understand, she does not bring any psychologization or inflection into it. She only possesses elementary knowledge and cannot express much, leaving her isolated. As Bresson would suggest, she is “closed, does not enter into communication with the outside world except unawares” (Notes, p. 51). Her speech is monotonous and sounds like a monologue. Her likeness to the model becomes a representation of her foreignness and isolation.

However, as she starts to learn the language, she becomes, as Bascayart so boldly suggests, someone who acts. By the end of the film, everything Xiaobin says in Spanish is said with fervour, enacted. She has come to embody the Spanish language while simultaneously acquiring that other language that is necessary to build a life in Argentina: she has learnt to act. Wohlatz meaningfully noted that “the language school could be understood as a rehearsal stage for a new identity after immigration.” Here, she juxtaposes the actor and what appears to be the model to highlight the process of self-realisation Xiaobin pursues through her language acquisition. She playfully unravels the acting of everyday life that is dependent on the characteristics of the actor Bresson condemned in cinema:

The actor projects himself before him in the form of the character he wants to seem; lends him his own body, face, voice; makes him sit down, stand up, walk; penetrates him with sentiments and passions he himself does not have. This “I” who is not his “I” is incompatible with cinematography. (Notes, p. 34)

However, Xiaobin’s role isn’t exactly free of projection. When they were shooting the first scenes of the film, Xiaobin’s Spanish was already far more advanced than what we see in the enactment. When Wohlatz encountered her, she barely spoke any Spanish but the shooting took place more than a year later. Furthermore, although Xiaobin isn’t a ‘real’ trained actress, Wohlatz did let her and her fellow language students partake in basic acting exercises and rehearsals. During the rehearsal process they tried to find an acting style that worked for Xiaobin and pleased Wohlatz. In an interview with Film Comment, the director is clear about her dislike for “actors who act out everything psychologically to try and explain their characters”, because she “feel[s] like life is not like that [since] we understand so little about us and the world.”

In the same interview, Wohlatz admits that in this respect, Bresson was an inspiration. Like Eugène Green and Straub-Huillet before her, she seems to have opted for a singular interpretation of Bresson’s choices, achieving a similar result through slightly different methods. With regard to authenticity, one could question to what measure this makes the performance of Xiaobin any more directed or artificial than that of Bressonian models. She is, after all, still re-enacting her own life, something that can’t be said about Bresson’s models. With El futuro perfecto, Wohlatz inscribes her work in an interesting tradition of non-naturalistic acting that intrinsically problematizes the artifice of cinema. The playful use of language elegantly underlines the way a new language and a new role – highlighted by Xiaobin’s name alterations to ‘Beatriz’ and later ‘Sabrina’ – collide in the life of the immigrant, with a sharp focus on absence and projection.

Notably, in one of the last scenes, projection is demanded from Xiaobin’s character in Spanish class. After learning the condicional simple (the equivalent of English type 1 conditional), she has to conjure up a number of different hypothetical scenarios for her life. The last dream scenario is filmed in a completely different style and offers a sudden surge of colour on the screen. Digital footage, amateurishly filmed and clearly conveying the feel of a vacation video, shows Xiaobin travelling in India with Vijay. She wears colourful clothes and humorously shows her embarrassment at being caught on tape by him. The clumsy handheld camerawork and grainy texture give the sequence an intimate and lively feel that is completely at odds with the rest of the film, including her other (slightly more melodramatic) hypothetical scenarios.

The reason El futuro perfecto doesn’t end with a scene elaborating on the titular tense was that Wohlatz wanted to use the conditional, “the grammatical tense that allows us to imagine,” which made it possible to incorporate Xiaobin’s future in an open-ended fashion. In a way, the futuro perfecto finds its illustration in the final scene, when Xiaobin sets out to trap a stray cat – resolving the earlier question of whether or not to have a pet, and the issues of domesticity it entailed – and succeeds. All other progressions are hypothetical, no more than projections. Xiaobin’s ‘I’, who is not her ‘I’, could be her past or future ‘I’, such are the possibilities of the actor and language student in El futuro perfecto.