Film history is often written down as a gossip column: Louise Brooks stole the lead role in Pandora’s Box (Georg Wilhelm Pabst, 1929) from under the nose of Marlene Dietrich, and earned her place in the actresses’ hall of fame. Dietrich herself only became truly prominent thanks to the lighting & magic of director Josef von Sternberg, after she was lauded during her early films merely for walking into the footsteps of the already sensational Greta Garbo. Mae West was a vaudeville performer stranded on a Hollywood set who had her chance to shine in the pre-Code sound era when they needed someone who could sing, and when raucous jokes were still tolerated; she was exceptionally lustful for a woman, providing, of course, that she wasn’t in fact a gay man. Joan Bennett was a talented actress, a pretty natural blonde who would get lost in the crowd due to Hollywood’s embarras du choix where blondes were concerned, until she changed her fate by becoming a brunette. Il Cinema Ritrovato does the past justice by displaying the actual work of all these women, from well-known films to very obscure ones, to highlight the acting talent behind their gossip-infused reputation.

It takes a bit of reading against the grain to see the 2017 Bologna festival as a showcase of iconic womanhood circa 1930. Brooks, Dietrich, West and Bennett were all present among the Cineteca’s picks, but as part of different programs: Augusto Genina and William K. Howard retrospectives (in the case of Brooks and Bennett, respectively); the festival’s Ritrovati e Restaurati section (Dietrich); and the Colette-endorsed film selection (West). In this Cinema Ritrovato wrap-up of sorts, I’m leaving out other equally notable women – with no clear alibi except for the limited attention span of the online format and the expansiveness of film history. Pola Negri, Brigitte Bardot, Joan Crawford, Jane Wyman, Dany Robin, Mary Nolan – who were also making their comebacks this year on the Bologna cinema screens – could by themselves be the subject of a different essay.

Are the thirties so long ago that they’re unrelatable for modern audiences? It would seem not. Genina’s Prix de beauté/Miss Europe (1930) – which credits Pabst and René Clair as writers – casts Louise Brooks as a young woman who has to choose between fame and personal happiness. Tell me this theme doesn’t ring familiar and immediate to anyone who grew up with Britney Spears and romantic comedies of the 1990s and I won’t believe you. The difference is that in 1930 the fun-loving, limelight-happy flapper was a seldom seen before model of femininity, and the beauty pageant was presented as something new and morally controversial. In Genina’s early sound film that largely follows silent film syntax, Brooks plays working-class Lucienne, a Miss Europe contender whose very conservative fiancée discourages her from drawing the spotlight onto herself. (Spoiler: Confronted with a choice, she settles for domesticity and regrets it. The ludicrously worn and torn clothes she wears at home suggest as much.) Brooks expertly conveys the girlishness of someone who suddenly gets a lot more attention than she could’ve hoped for (way too suddenly, in fact – it’s only the actress’s infectious enthusiasm that makes up for the thinness of the script). She also gives off an exonerating naïveté in facing the men who pursue her, as if she can’t guess their intentions. Among the most amusing episodes in Miss Europe is the dinner conversation with a maharajah (possibly an impostor) whose courtship techniques betray his lust and – radically worse – his poor taste in metaphors. Far from fitting into the gold-digger cliché – of the street-smart woman who cashes in on her looks –, Lucienne is suddenly faced with ascending to heights she could have only dreamt of and then facing the judgments of those who scrutinize her from below.

The Dietrich persona is more self-conscious and worldly compared to Brooks’ youthful charm, but in the best of her films, she shows more pathos than cruelty. Robert Land’s 1929 I Kiss Your Hand, Madame/Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame presents her as a high-maintenance divorcée who lets herself be seduced by a Russian count, until he is exposed for working as a waiter, though later he again reveals himself to be a genuine aristocrat. (The woman’s interest in him fluctuates with status.) In glamorous clothes and glamorous lighting, this pre-Sternberg Marlene already has the unattainable-woman allure well rehearsed, though she is equally expressive when regretting discreetly to have rejected her suitor. The film doesn’t have the flamboyance of Sternberg films and her heroine is lacking in complexity (the film was mainly a vehicle for her co-star, Harry Liedtke), but Dietrich does the most she can with the part, mainly by bringing inexhaustible amounts of dignity to the role of this opportunistic beauty.

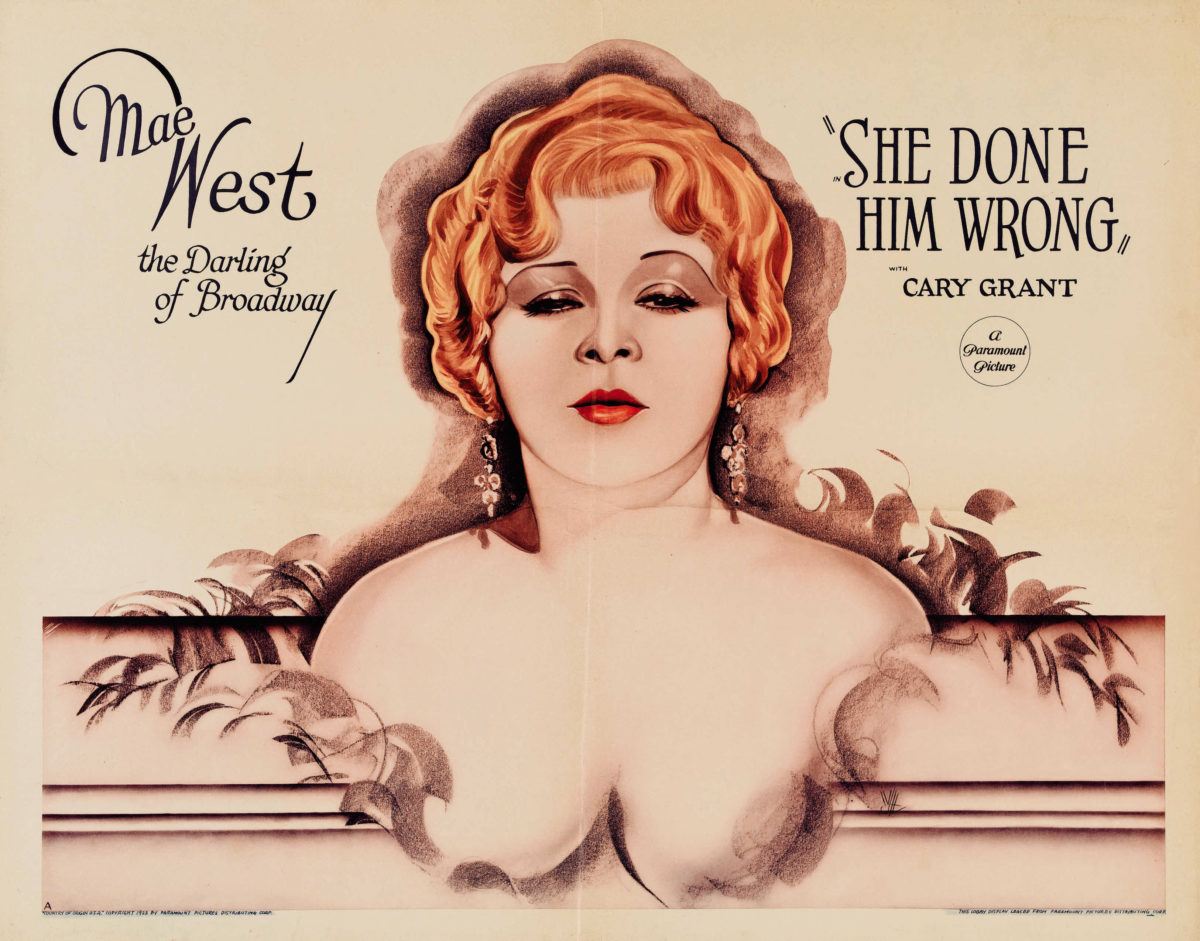

For an absolute lack of repentance, one should look no further than actress and screenwriter Mae West. Lady Lou, the typically promiscuous and cynical protagonist of She Done Him Wrong (Lowell Sherman, 1933) – who is, in her own words, “one of the finest women ever walked the streets” – brushes off frequent and obvious come-ons, adultery, workers’ exploitation and murder without breaking a sweat. (I’m not in any way condoning the aforementioned deeds, but one has to wonder why chasing men around was always the most shocking and indefensible part of everything her character was doing.) There is about as much plot as in your average studio film, but it serves to display West’s resilience to moral judgment and frequent one-liners. Asked whether she hasn’t ever met a man that could make her happy, she responds: “Sure, lots of times.” When consoling a woman who was unlucky in love, she assures her that her breach of propriety is not worth crying over: “when women go wrong, men go right after them.”

Lady Lou navigates between her business partner – who obligingly looks the other way when she’s flirting and holds her in high esteem as a trophy wife –, a hunky Russian kept man and a policeman (Cary Grant) who seems miraculously to resist her very open invitations. In one of two films in which she plays opposite Grant, their opposites’ dynamic works convincingly, in that her aggressive straightforwardness only makes him step back like a gentleman, and this somehow builds a stronger bond than with the men who fall right into her arms. As with the screwball films (also known as remarriage comedies) that would later turn Grant into a legendary leading man, the female protagonist has to choose among her suitors, and in the end she commits to the one who knows her best. The artifice of a clear-cut ending is more obvious in pairing off West and Grant, since she isn’t exactly the poster girl for monogamy, but this plot resolution is still a leap ahead from the character type of the prostitute who must die for her sins. In fact, it’s even less punishing than our contemporary Amy Schumer’s Trainwreck (2015), in terms of how female libido is accepted as a life-long and sympathetic trait. (Not to mention that West was forty at the height of her film fame. Schumer is presently thirty-six and has to periodically spoof her non-standard desirability.)

To make a clearer point about how women are traditionally judged by their behavior toward men, let’s take a standardly accomplished studio film shown this year in Bologna: Universal Pictures’ Young Desire (Lewis D. Collins, 1930), starring Mary Nolan as Helen, a disillusioned carnival performer who meets a young man from a wealthy family. Aside from a meet-cute and a few of Helen’s not-quite-West-level cynical lines about getting the short end of the stick, it’s a pretty dull and moralistic film, the tension deriving from whether a girl with her past could ever make a good wife. (There’s no clear indication that she’s unsuitable except for having somewhat rowdy friends, but social mores dictate that we should suspect as much.) By contrast, West’s I’m No Angel (Wesley Ruggles, 1933, also starring Cary Grant as finalist leading man) is unburdened with moral bias, although it features another carnival performer with more measurable misdeeds (again, she is involved in potential manslaughter, but the worst she has done in everyone’s eyes seems to be seducing men). I’m No Angel even goes so far as having West’s character defend herself in the court of law against – basically – popular prejudice toward mature unmarried womenMae West’s overt sexuality is so subversive to Classic Hollywood standards that it’s hard to clearly state what her characters are implied to be. Are they kept women? Are they prostitutes? Since her protagonists aren’t presented strictly in rapport to men, there is insufficient evidence for either. The most well-researched hypothesis belongs to Jessica Hope Jordan in her volume The Sex Goddess in American Film 1930-1965: Jean Harlow, Mae West, Lana Turner, and Jayne Mansfield, published at Cambria Press, NY, 2009. Jordan cites the early-20th Century social habits of the so-called “charity girls”, young working-class women having low-income jobs who would have affairs with strangers in exchange for their presents and attention.. In distinguishing West films from standard love stories, it’s also frequently noted that her heroine is at the center of a more complex network of characters, including many who were usually marginalized in Hollywood films. Her films passed the Bechdel test before it was available for testing – she shows solidarity toward working-class and African-American women as often as she shows contempt for upper-class ones.

However, what Brooks, Dietrich and West have in common – along with the majority of their colleagues – is that their persona was closely tied to their sexuality. In the case of Joan Bennett, this was usually more complicated. She is best known for two Fritz Lang-directed noir films – The Woman in the Window (1944) and Scarlet Street (1945) – where she plays deceitful women opposite Edward G. Robinson’s naïve men. However, in both these films as well as in Max Ophüls’ outstanding The Reckless Moment (1949), there is greater intricacy to how she uses her femininity. Unlike standard-issue femme fatales, given the circumstances of her own life, her heroine is the victim as much as she is the perpetrator – she is caught in a tight spot and breaking the law becomes the only way to survive. With Bennett, even her seduction techniques have a grounded quality, they are more a matter of interpersonal responsiveness than of being provocative. William K. Howard’s The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932) already places her in that ambiguous position, literally in a defensive stand. She is guarded, as a default state, rather than impulsive. Her eponymous character is on trial for having murdered her cheating boyfriend, although she denies being guilty. Inspired by real murder stories (or rather genuine tabloid scandals, to be more precise), Howard’s film is pretty self-conscious about the mass appeal of such a trial: a pretty young woman, facing a death threat apart from a broken heart, is a strong hook for newspaper stories and radio broadcasts. (Chicago, anyone?) While The Trial… is more of a comedy of manners than an actual murder mystery, it does depend on her ability to withstand prolonged scrutiny without becoming monotonous.

Naturally, these four are part of a much larger constellation of female stars of the 1930s and reading them as social projections of womanhood risks being too broad. However, especially when examined side by side, they are sufficiently complex or creative to refresh our memories, and maybe challenge our prejudice, about the mass culture of a bygone era. When the next Bechdel-friendly blockbuster pretends to be something new and unseen in terms of female empowerment, you can remember these ladies.