Shooting up a genre film with a heavy dose of cultural criticism might have been the bread and butter of the 1970’s but seems positively out of style today. Where are the new Romero’s and De Palma’s or the odd followers of curiosities such as Bob Clark’s Deathdream (1974)? Few are taken to the cause of driving home political messages through horror and allegory. And then there’s Belgian director Pieter Van Hees, who revived the practice in the final instalment of his trilogy ‘Anatomy of Love and Pain’. Following up on Linkeroever (2008) and Dirty Mind (2009), Waste Land (2014) doesn’t play coy with its rather overt subtext by presenting Brussels as a smouldering, near-mythological cityscape that’s teeming with the memory of darker days. Zeroing in on the story of a decentred policeman named Leo – after Belgium’s fabled despot Leopold II, sole owner and tyrant of Congo from 1885 to 1908 – Van Hees wilfully picks the scabs off of a buried topic by letting personal and collective trauma collide. A fervent believer in the moral reprehensibility of negating a troubled chapter in our national history, Van Hees talked style, influence and ideology in an interview conducted in the wake of last year’s Young Critics Workshop at Film Fest Gent. “With so many scary things happening in the world of today, the movies we make should at least try to negotiate cultural distress.”

Was it always your intention to make the entries in the trilogy as genre films? How important are the conventions of a specific genre to create a successful character study?

I’ve always nurtured the idea that the individual films should be singular exercises in a specific genre. Not because I’m interested in making a genre film per se, but because I’m fond of the research they require. I like films that combine genre elements with a true-to-life feel. That’s what the glory days of the American independent cinema of the 1970’s were about. Godard and Cassavetes approached realness in genre films and in that process expressed the best of both worlds.

Linkeroever has a genuine Flemishness to it and the film addresses what might be lurking beneath the surface of an area that is generally looked upon with some distaste. The neo-colonial discourse of Waste Land also taps into a decidedly ‘Belgian’ affair. Do you deliberately work with material that stays close to home?

You have to keep in mind I do create my output here. I don’t want to exercise judgement, but The Loft (Erik Van Looy, 2014) isn’t a Belgian film, at all, not even in its initial Flemish version. To set up Waste Land I drew a lot of inspiration from Brussels, just as the actual topography of Linkeroever inspired me back in 2008. I had never been there before but had a friend who lived in the neighbourhood. Linkeroever is such a strange and sinister place. When he came up with the idea to shoot the film there, I immediately obliged. Linkeroever screened at Fantastic Fest in Austin, Texas. Afterwards, a member of the audience came up to me, in shock, saying: ‘man, this film is about my state, we actually have these holes and wells in the ground’. It’s no secret that Americans are Celts by origin and that Celtic mythology is still alive and well in the US, even to this very day. I long had plans for an international remake of Linkeroeverthat would play in one of the many Irish communities in the States. It’s funny how local concerns can reverberate on such a universal level. Waste Land screened in Korea and Toronto. If I had decided to write Waste Land as a poem, it wouldn’t have reached such a widespread audience. I loved the challenge of finding the adequate form for a local subject that could have an equally profound effect on someone living in Canada or Korea.

Any explanation for your fascination with the occult?

All of my films have an affinity with the spiritual – if you want to label that occult that’s fine by me. I love to think that there are other realities besides the one we know of: they exist if you believe in them and that’s a predilection I love to make part of a story. I always had a fondness for Gabriel García Márquez. There’s a story by Márquez that features a village housing a 300-year-old grandmother, no questions asked. It’s an implausible element that perfectly fits the universe he creates.

What about 1970’s horror flicks? Linkeroever and Waste Land tie in effortlessly with folk horror like The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1973)or The Dunwich Horror (Daniel Haller, 1970). They are similar to Roman Polanski’s apartment-thrillers as well (Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, The Tenant).

Polanski is a living source of inspiration, much more so than any horror that’s ever been made in the seventies. What gets me going about the American horror cinema of the seventies is the fact that a lot of the people who were working in the special-effects department at the time had actually been to Vietnam. The make-up they were coming up with was actually inspired by the carnage they had witnessed during the war. As a consequence, the films are infused with a whole new level of reality. I think I read somewhere that the men responsible for the effects used in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974) and Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976) served duty in Vietnam and funnelled their wartime experiences through to the film set. It’s hard to imagine just how fucked up the US was at this point in history, but at least you have a couple of films that try to show it. Whenever most producers or directors do horror now, they make it parody or pastiche, devoid of any socio-cultural context. And yet, there is a lot of terrifying shit happening all over the world that doesn’t make it to the big screen. I’m not a director who whips up a horror film just for the sake of doing one. What’s the use of scaring your audience? But, if you’re able to channel a society’s fear and other cultural anxieties into a work of meaning, you’re on to something.

I initially considered Waste Land‘s neo-colonial angle as a device to articulate psychological distress through a subject that is somewhat taboo – an external anchor to symbolize the main character’s internal battle with the lingering presence of his own tyrannical father. You don’t have to be a cultural critic to cite one of the dark passages in our national history, yet more seems at stake here.

Colonialism isn’t dead to me: it’s very much a thing of the present. Belgium is one of the most racist countries I know, with very few immigrants getting the opportunity to outgrow the appalling mess they’re living in. Even getting an apartment is tough. Waste Land does zoom in on a character that’s dishevelled because of the way he grew up, but there’s a lot more to people than just their personal history. Each and every one of us is the product of the environment we’re raised in and that legacy runs deep. Germans still feel the burden of Nazism. They could be twenty years old and feel it, whether despite or because of the extensive discourse Germany has spawned about its atrocities. It’s quite a different story where Belgium’s concerned. There are hardly any films, books or theatre plays that acknowledge and work through the faults of our past. All of my African friends share the sentiment. They feel like they don’t have a voice because their history isn’t addressed.

Did Waste Land have a moodboard? A concrete source of stylistic inspiration? All of your films share a strong sense of atmosphere.

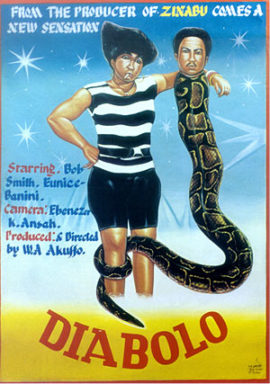

While the theme of the film came to me quickly the visual style did not. I really had to search for the right ‘look’ and started out by collecting pictures and paintings and flyers and stickers for urban parties I picked up around the city. Suddenly, it hit me that I had gathered a lot of stuff in brown, orange and yellowy shades. This was a colour scheme I wanted to try out because it suited the film and the city I was shooting in. Hunting for the right locations became an extremely important part of the pre-production. The spaces we were interested in had to look the part and if they were, so to speak, purple instead of ochre, we had no use for them. I love the yellow tiles you see all around Brussels and knew these would bring the right colour to a scene. We also made use of an old ex-police station close to Schaarbeek’s city hall, completely authentic and perfectly matched with the intended palette. I tried my best to look for buildings and spots that were a bit ‘off’ in structure or architecture. They suit the film because you never really know what’s happening for real or just inside Leo’s head. For a while there I thought of mixing in an extract from Diabolo (William Akuffo, 1991), one of Ghana’s classic horror films. I wanted to use some of the film’s footage for the videotape the inspectors find. Eventually, appropriating a real piece of the film didn’t suit me any more. I did however take the ritual in Diabolo as a point of reference for the one I shot in Waste Land. Gerhard Richter’s work came to me in a stroke of coincidence. For the illustrious tape Géant is featured on, I was set on combining Richter’s ‘flurry’ aesthetic with the attraction of Diabolo‘s crappy polaroid quality. To achieve this effect I literally used the oldest and baddest video camera I could find. Surprisingly, even that looked too good. We had to lower the resolution during the grading and blow up the image afterwards to achieve even more noise. With the footage slowed down, the scene ends on an image of Géant that’s nearly standing still. It’s quite iconic, fully inspired by Richter’s dirty streaks but transferred to video. It’s only a short moment in the film but it’s sure to leave an impression.

Come to think of it, one of the extras in the scene actually participated in a similar ritual in Africa. When you’re shooting stuff like this in a dilapidated building in Anderlecht, you’re sure to feel all kinds of strange vibrations. Another source of immediate inspiration was an anthropological study of Congo by Filip De Boeck and Marie-Frangoise Plissart called “Kinshasa: Tales of the Invisible City”. On the cover, there’s a photograph of a young black boy on a white plastic lawn chair and an overhanging light that makes the image incredibly eerie. I thought, if I’m letting my Géant appear in a stadium… it’ll have to look like this. To create a similar sort of atmosphere for the film I was on a constant lookout for things and bits that were true to life and Bruxellesque but had a surreal potential as well. Brussels by night looks yellow – I could have just emphasized the streetlights in this scene but wanted to turn it up a notch, as the yellow colours already were omnipresent throughout the film. The extra splash I used served to code it as one pertaining to a higher dimension. The funny thing is that at the time I remembered a painting of Lumumba by Luc Tuymans. I can’t recall its title but it depicts a tree with an old car parked next to it. As it turns out, I unconsciously recreated it. I did not plan to create that image, but it’s out there. I don’t think there’s anyone who will recognize it when they see it in the film.

I assume the plastic arts are a great source of inspiration for shaping equally iconic images on screen.

I looked at Léon Spilliaert for a while. I’m a fan of his work and could have easily shot the film in a Spilliaert palette, even though his paintings are too monochromatic for a city like Brussels that’s seedier of both light and colour. All of the lights in our subway stations are different because they are frequently replaced by people who don’t take the effort to use the same bulbs. In this way, you end up with a botched look that Spilliaert’s style does not have. I needed Brussels’ griminess, the way everything spills over into something else. I wanted orange, brown and the dark tints of film noir spliced with neon lights. Shooting in Le Mambo, the African club on the Waversesteenweg, was heaven. I could just turn on the lights and roll camera. Another thing I absolutely wanted to include was the neon cross of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart. It was perfect for the shot of Leo descending Koekelberg Hill. The only downside was that every time we wanted to start shooting the cross wasn’t lit. Like a bad omen.

Speaking of which: Waste Land ends on a rather religious note. Where did that come from?

We Belgians have a catholic background, even though it’s not as visible today as it used to be. I named Waste Land after T.S. Eliot’s poem that features the Arthurian vegetation myth of the Fisher King. As the legend goes, the ruler’s impotence affected the fertility of the land: he had to die in order to restore it. The closing of the film is a throwback to the myth. The image of one wounded in the legs, groin or upper body also calls to mind Saint Sebastian and Jesus. They’re old archetypes that tie in ‘wounding’ with the act of getting rid of a sense of guilt – quite suiting for the theme of the film and our Catholic predilection for guilt. I’m no intellectual but I did want to endow Waste Land with a deeply spiritual layer by using these archetypes. These images aim to strike a spiritual chord, regardless of the film’s bigger theme of racism in the modern metropolis.

It’s not an easy feat to add a metaphysical dimension to a genre film, but it’s always interesting to see a director use a well-known template to a different end.

I agree, even though I love films such as Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Banishment (2007) and Leviathan (2014). Zvyagintsev makes it clear from the outset that he’s creating deeply spiritual films, without making excuses for it. These are films that command their audience to sit still and immerse themselves and I have tremendous respect for that. As both a filmmaker and a spectator, I prefer to stumble in on it: it touches you deeper when you don’t see it coming. Then again, it’s hell to drag along the conventions of a genre. When you’re doing a police drama, people expect to find out ‘who did it’, so it’s equally important to write in scenes that stick to this need. Unfortunately, they take in a lot of space and sometimes feel redundant because they’re not what the film is about. It’s a delicate act to balance.

A word on your use of exploitation elements?

I’m a big fan of Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009). It’s the one film in his oeuvre that spoke to me. I don’t mean to suggest that I don’t admire his other work but it never really managed to draw me in. Antichrist was an altogether different experience, even if that film clearly is von Trier’s exploitation flick. I’m aware of the fact that people who might be looking for an art film will consider Waste Land too superficial on account of its use of genre elements. Those looking for a purely entertaining 90 minutes will be soured by the outré qualities of the end sequence. It’s a key factor in my approach to creatively mix these elements and have pulp culture meet with profound philosophical questions. If you read T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land, you’ll come across quotes from ancient Greek drama and Wagner to fractions of dialogue Eliot jotted down in a seedy bar. All are put on the same level.

A closing anecdote on the period of shooting?

We had to shoot a lot of material within a limited amount of time, always racing. Every creative decision was called at high pace. I get the impression it invests Waste Land with a certain energy, like the film absorbed our state of mind of being awake for days on end. Cinema is an active medium. There comes a point during a shoot when you only have about ten minutes left to get a certain scene. Your actor’s sick, but you need your footage and it’s up to you to get it now. You might have been thinking about the scene for five years, but it’s in that moment that you have to make it work and kill your darlings: throw out stuff that seemed indispensable in theory, but not in practice. Cinematography-wise, I had set up a few basic rules with my DP, Menno Mans. He knew I wanted a lot of natural light, with ‘pure’ sources of external light invading the indoor scenery. We started off on tripod, levelled, with clean lines. From the moment Leo’s character started sliding, we discarded the tripod for a more deranged way of shooting. As long as you have a couple of clear-cut rules to swing by, you’re safe to experiment.