British filmmaker Terence Davies’ latest film, A Quiet Passion, is a biographical piece about the life and work of American poet Emily Dickinson. A subdued film with boisterous performances, it engages with the poetry of Dickinson’s work via parallels in the visual grammar as well as voice-over recitations. The film features a strong focus on the passage of time, verbal wit, and outdated modes of thought.

With a warm smile, Davies proved a perfectly congenial fellow and a distinctly British one at that – I couldn’t help but notice his beverage of choice: black tea with a splash of milk.

MP: What was it specifically about Emily Dickinson that compelled you to tell her story?

TD: Well, I’d heard her poetry when I was about eighteen. I lived in the northwest of England and the local TV station was called ‘Grenada’. They had these little documentaries every Sunday. One was about Tom Jones (a very young Tom Jones) and one was about Emily Dickinson. I’d never heard of her. It was Claire Bloom reading her poetry and the very first one she read was ‘Because I could not stop for Death’. I thought, “I’ve got to go out and buy them.” So I went out and bought them, and read them, and loved them. But I had to work – I was only eighteen. I was a very lowly bookkeeper. I read her just for pleasure but sometimes an idea will be in the back of your mind for a very long time and something will trigger it. About four years ago I really thought, “It’s such a strange life she lived,” because she only left home once and then never left home again, ever. I think I read six biographies, and found that this was just such an extraordinary life that was lived very intensely but at home – it was never boring. I think the reason it’s not boring is because her family is the repository of all that’s wonderful and all that’s terrible in the world. She wanted her family to be like that and not change forever. Of course you can’t have that. We all want to be a part of the Smith family in Meet Me in St. Louis, but alas, that’s not real life.

Did the poem ‘Because I could not stop for Death’ give you the idea for the ending scene from the very beginning? [The ending scene features Cynthia Nixon’s Dickinson reciting the poem in voiceover set to images of her own funeral – MP]

There were two funerals – her father’s funeral and then hers. We used the same hearse [for both scenes – MP]. We’d done the father and then we’d gone to the cemetery to get the last shots and then got back quite late to do hers. I thought, “It would be really boring if we just do the same thing.” The assistant director [Lynn K. D’Angona – MP] had seen the back of the hearse, and there’s a lever to keep the casket straight. I don’t know what made me think it, but I just thought, “Well if we’re looking down on it, it would be much more interesting.” That’s just geography, that’s not drama. It’s a top shot looking straight down. It came to me on the day. [Chuckling]

How early on did the idea come to have her actually read the poem over that scene?

Oh that was always the case; she would always read the last two poems as they are in the film over her own funeral and then when we’re inside the grave. So that was the same. It just looked more succinct. In a way you don’t know where you are once you’ve come up and looked down at her, where do you go from there? Then we go to her sister, coming in and laying the flowers on the coffin, and then we come up again and then do this [gesturing camera motion movement in the air]. It just makes it slightly odd. The father’s funeral is shot in a very conventional way. Just having them coming out again with umbrellas, that’s not interesting. What are the things you remember at a funeral? Do you remember the coffin? Obviously, because the coffin is always a shock. The Victorians were obsessed with death, in a way that was really unhealthy – but then there’s also a lot of death all the time. I just thought, “make it slightly abstract.” It’s obviously got to be a hearse but it can be abstract. And if it’s abstract, then it’s more interesting because you see funerals as they literally happen and go on their way, but if you’re outside it, you see other things. When we got the first reviews in England, I was up in Liverpool and they were lovely reviews and everyone was very happy and one of the producers said “I’ll take you to the station in the car.” We took a detour and as we came out by the University there was a cathedral and there was a funeral cortège and it was so… it took all the joy out of the day, but you just noticed what people did; being embarrassed at embracing someone, and the coffin was white and you just saw these blank ashen faces and – you know, you can’t forget it. But those are abstract if you actually look at them.

Speaking of the abstract, one of my favorite sequences in the film was when you have Dickinson reciting one of the poems, and then we have the silent, visual rendition of that. I thought that was wonderful. Obviously you have a lot of shot-reverse-shot sequences with very poetic editing and punctuation, but how did you decide to have restraint with visual adaptations of the poems, because we hear her reading a lot of them but we only really see this one adapted visually so directly.

Well the problem with any kind of recitation is: how do you make it seem as though it’s from her point of view, from the poet’s point of view? Two things arise from that. First, where do the poems fall? It has to be instinctive. You feel it: “the first poem’s got to be put here.” So it comes after she’s been chastised by Miss Lyon. In a way she’s been left in that room on her own to contemplate how evil she is, but she’s not evil, she’s deeply spiritual, she just won’t go in for any of this evangelical nonsense that swept both England and America before and during the American Civil War. So it’s “where do they fall?” and the second thing is “are they being used in counterpoint?” When she’s standing at the window and the light is streaming in – and most of that was real light, we had lit it but it was the natural light that came through –, in that intense moment, it’s the first time we know that she’s a poet. She’s saying, “If you have these intense moments of beauty, you’ve then got to pay for them.” Somewhere down the line you’ve got to pay for that ecstasy. You don’t get it for free. And it’s nice to drop it in there but it’s just as nice sometimes to juxtapose something that is completely different. The way Cynthia [Nixon – MP] read the poems – we originally did that as a guide track but I used them in the final film because they were just so good. ‘Because I could not stop for Death,’ for instance I’d always heard as being kind of really elegiac but she read it with this kind of rather wry detachment, as though it were someone else who is dying. Which of course makes it so powerful; it’s the perfect antidote for what you’re looking at. It’s almost funny but it just stops short of being funny. It’s very ironic. Those things present themselves to you when you’re writing it, they present themselves to you when you’re shooting it, and they really do present themselves to you when you’re cutting it. Do we have it here? Do we have it there? Do we leave this completely silent or not? That’s the joy of the terror of editing; it has to be spontaneous. Things happen that you hadn’t thought of, and that’s what I love: some tiny thing which on a stage wouldn’t even be noticed… The one that always strikes me (and I’ve seen it now hundreds of times) is when the mother has a stroke and she’s lying on the bed and she just goes like this [miming a small movement]. You can’t direct that. That’s… I don’t believe in God but somebody’s looking down, giving you that.

When she has that stroke, we kind of see her framed in the doorway, and it’s this great big wide frame (Cinemascope) and then in the next shot I was struck by how much open space it felt like we suddenly had; that she’s in bed with her two daughters next to her, compared to this restricted door frame and I noticed this vertical compression happening in a few other places where you’re using this continuously as foreshadowing for death or relating to the shape of a coffin…

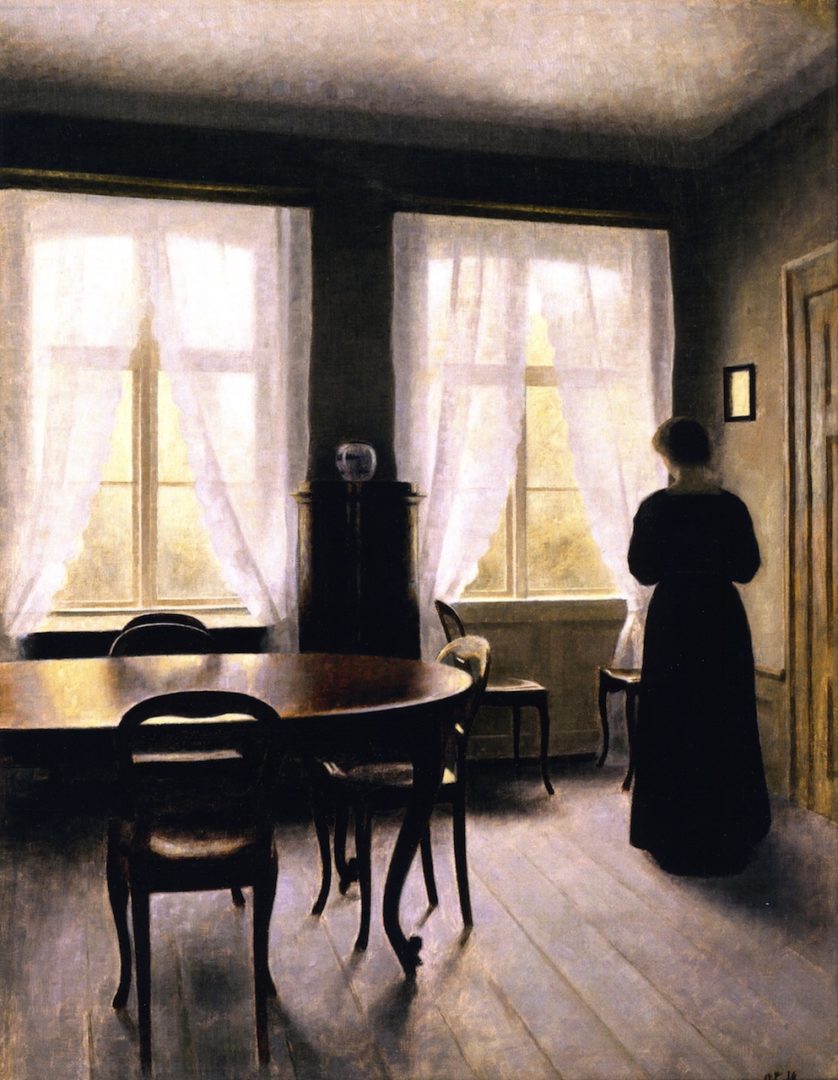

I’m obsessed with symmetry. I don’t know why, I just love things to be symmetrical. I do try to get some asymmetrical shots in, I do try. But I like the symmetry. There’s a Danish painter at the end of the 19th and beginning of 20th century called Vilhelm Hammershøi, who’s like Vermeer but with a kind of northern smudge-light. There are open doors or corridors with nobody in them, or if there is someone in them, it’s a woman with her back to the viewer. They’re wonderful paintings, they’re really strange. But it’s all about verticals and rectangles. It’s almost like Mondrian but it’s… much more… lovable rather than mathematical. Mondrian is someone I just can’t get worked up about, I have to say. But aside from this symmetry in the house, sounds are also incredibly important. Because when you’re in a house, and there’s no natural sound except you walking up and down stairs or moving about, you hear it. That’s what you do. When I was growing up we were very conscious of the house settling into silence at night. You could hear it. So it was important to get that sense of the house – it’s never dull. It’s just people moving through empty rooms, but I love that.

And do you consider these kinds of little sounds a part of the punctuation [of the film] as well, alongside the editing?

Yes, yes. Sounds sometimes can be funny. I mean, the teapot is deliberately slightly over-recorded, because when you are inside and it’s uncomfortable, you hear every sound. It seems incredibly loud. I used to go to drama class every day as an amateur and a friend of mine there said “Come up for some tea on Sunday at 3 o’clock and let’s watch the football game.” I can’t bear sports, football especially, I just think it’s so boring. Anyway, we were watching this bloody football match and I was given an apple. When you don’t like something, you know, you get very bored very quickly, and I thought, “Oh I’ll bite into this apple.” And I went, [imitating loud apple crunching sound] and he looked at me and they’d almost scored a goal and then missed it. And so I had this piece of apple in my mouth and I thought, “Well I’ll wait until there’s another dull bit.” And then I went [imitating a myriad of smaller apple crunches]. He looked at me because they’d missed another goal and he said “You’re doing it deliberately!” I’ve never forgotten, and it sounded so loud.

On a completely different note, there is a sequence dealing with the American Civil War. Why did you take that moment away from Dickinson to focus on the Civil War?

Austin Dickinson is made to stay at home and not fight. A lot of people didn’t see any battles. It’s not like modern warfare, where you bomb the civilians. It was something that was removed; you never saw it. In fact, when the first battle of the Civil war took place, people went out in carriages to look at it. If you could imagine a war that is taking place but you don’t see it, it’s much more powerful… because you don’t know what’s going to happen. What would’ve happened, say, had the North been defeated? What would’ve happened? They would’ve had slavery. Although the reality is, the founding fathers all had slaves. So it was an idea of “we’re all equal, but some people are more equal than others.”

Which we see continuously with Dickinson pointing this out [in the film] and that even if they abolish slavery, women’s rights are still horrendously behind, and this bit about relating marriage to slavery?

Because it was if you were a woman. You became a man’s property. I mean, we can’t imagine it nowadays, but that’s what happened, you just became this property. It was usually about money. It is a kind of statement, you know? And there were certain things that were very restricted by convention as to what you could or couldn’t do as a woman. If you were not working class you were not allowed to make a living, and even then, in the 1840s, the former students became teachers and as soon as they got married, they were dismissed. So life was restricted, even in America, although there are many more similarities than anywhere else. As soon as you got married, your job ended. Let’s not forget the men were oppressed as well. By being the oppressors, they oppressed themselves. I can remember when I was growing up, no man ever cried at a funeral. If you wanted to cry, you went out on your own. You just didn’t do it. You’d be told – I remember hearing women say to their husbands, “No tears. I’d be embarrassed.” So you were restricted then. You were expected to go out and get money. But there were certain things as a man you just could not do. And people forget that as well. Of course, if you’re the one who’s oppressing, obviously you’ve got more advantages than those who are oppressed. But it still imposes certain restrictions on you. Because you’ve got to uphold what was expected of you. Not even that you’ve got to uphold it, but you feel that it’s what you’ve got to do. That’s the important thing. But that’s what makes human beings so interesting.