A classic horror film technique is to cut away before revealing something terrifying, whether it’s a monster, a grisly murder, or some sort of harrowing revelation. This is an act that creates an absence—a question lingering over The Horrifying Thing—but more than that, a new feeling emerges within that empty space, something that can only exist before that absence turns into presence. These moments leverage both the existential dread that comes from the fear of the unknown, and that constant uncertainty about what occupies the empty space that the camera refuses to show.

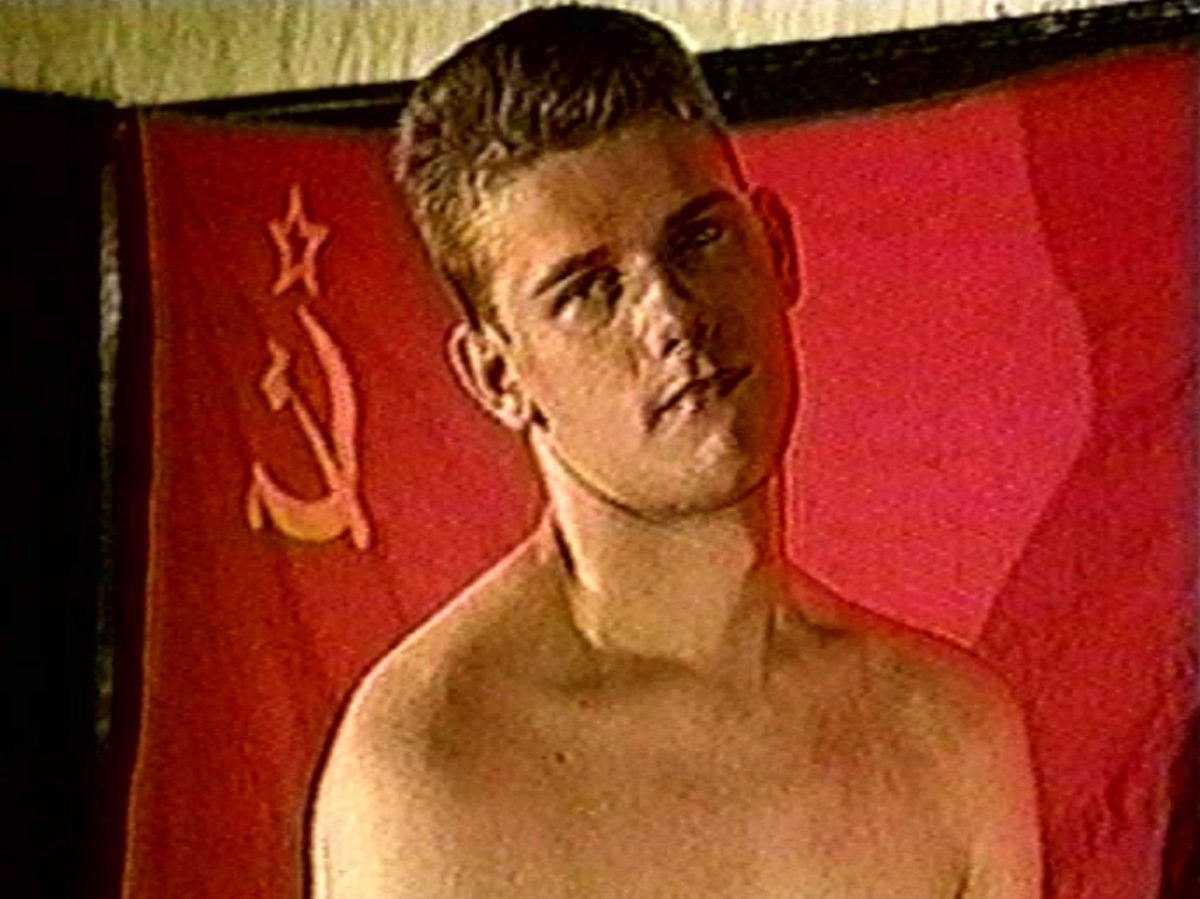

It’s this relationship between what’s revealed by the eye of the camera, and the absence of what it withholds, that animates the found footage films of William E. Jones. His work takes adult films from the 70s and 80s and repurposes them, often by removing sex entirely, creating a new language of desire and eroticism in the space that his cutting technique leaves behind. Jones’ films incorporate the desire for capital and capitalism in The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography (1998), the tension of cruising in All Male Mashup (2006), and V.O. (2006), which, by taking the dialogue of art films, and the imagery of erotica, creates a strange, genre-bending world. Porn suddenly becomes political, or like a pre-shootout sequence from a Spaghetti Western—three men staring at one another, the camera focused on their eyes, the details of their faces; its a sequence that recreates the beats—with the camera, with narrative, with tension—of the iconic sequence in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly when the three gunslingers face off.

By removing the sex from porn, Jones changes how desire can be articulated. This becomes an act of narrative subversion; in adult films, sex scenes function as narrative climaxes in the same way that song-and-dance routines do in musicals. In the absence of sex scenes, these narratives take strange new turns, as does the landscape of desire that the stories exist within.

Large sections of All Male Mashup are dedicated to the act of cruising; something that at once articulates desire—and the danger often inherent in it when considered through a queer lens. Looking for a partner in this way is something that’s imbued with tension, both from a sexual perspective, but also one that has the spectre of violence lingering over queer characters—someone that they approach might be violently homophobic, and these sequences that navigate queer desire, often in public spaces, put the desire to be openly queer at odds with what the wider worlds of these films make of queerness, Full of both erotic possibility, but also the very real threat of danger.

Cruising on screen also acts as a mirror for how Jones manipulates the idea of narrative, from both a storytelling and erotic perspective. By focusing on cruising as an act of both physical and narrative movement, Jones provides a kind of storytelling that moves towards a climax that never comes, reframing what desire looks like in the process. Rather than having desire appear through sex, Jones creates a desire for some hitherto undefined thing: a propulsive act of searching, that can only exist when the narrative – and sexual – climax is cut away from. Rather than ending on an anti-climax, this technique of filmmaking formulates a new kind of desire; for potential climaxes, finding power—both artistic and erotic—in a lingering sense of possibility.

The erotic desire to look, search, and find, in All Male Mash Up, is transformed through simple acts that become charged, whether it’s driving along streets late at night or buying clothes with a partner. In one scene, two men go shopping for denim and leather gear together. One tries on a black denim vest and his partner sizes him up a little; he squeezes the other’s shoulder to feel the material, before the two of them go over to a rack of outfits and look at cop uniforms. The camera zooms in on details: material, badges, a hand moving up a leg. By then cutting away, Jones severs the explicit link between the caress of clothes and the sex that presumably follows. The clothes become the site of eroticism, providing the moments of contact between the men, who are loaded with sexual potential. By focusing on these details, Jones changes desire into an idea, or an archetype.

Archetypes feature throughout Jones’ work. All Male Mashup and V.O. contain comical, stereotypical openings to porn: a pizza delivery, complete with the assurance that “HE DELIVERS.” In All Male Mashup, the scene fades to black after the delivery man knocks on the door, replicating the classic fade used for characters who were unable to consummate relationships in older films—it allows Jones to put his adult films into a dialogue with Old Hollywood classics like Casablanca (1942), or the dreamlike reverie of the most romantic moments in Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). In V.O., the pizza delivery boy makes it into the house, and talks to the man inside: about the price of the pizza, and the old victrola player on a table by the doorway. It’s the music from the phonograph that causes the film to begin in earnest—rather than playing music, it plays dialogue from another source: “now you must clearly visualize the negative agent that is aggressing you.” The image cuts from the pizza delivery boy to the victrola, moving deeper and deeper into the blackness where the audio is coming from. It’s this transition that allows Jones to not only begin splicing together the imagery of adult films and the audio methods of the arthouse, but that allows V.O. to descend into multiple, complex layers of fantasy.

It’s in this space of fantasy – through clothing, performance, and the decision to cut away – where Jones’ landscape of desire reveals itself. While Jones cuts out the sex from sex films, it isn’t prudish or censourious; instead, it allows him to widen the scope for the forms that desire can take: as cruising, costumes, or small acts of intimacy. There’s a clip in All Male Mashup of two men watching a Chuck Norris movie at a drive-thru while glancing at Tom of Finland images—hyper masculine, leather-clad men—and still images of porn that goes to the heart of this point, through both the ways in which it eroticises the body and masculinity of Chuck Norris’ persona, to the importance placed on these images of erotica, even and especially, in a world where no sex is seen. Although there’s no physical consummation, the ephemera of erotica still exists; through Tom of Finland, or a supercut of marquees with SEX emblazoned on them. Just because sex is cut from the screen doesn’t mean that sex or sexuality are absent from the world itself; in many ways, Jones shows that sex is always there, and that removing the act is a way of reconfiguring how we understand it.

Jones’ creation of absence in adult film asks more existential questions about the genre itself: what defines porn, and what can porn be – or be seen as – when sex is removed. A nighttime cruising sequence in All Male Mashup deploys an ominous synth score and uses film noir stylings, while the music of a poolside scene evokes a camp parody of something like Jaws (1975). In V.O., Jones presents a triangle of men looking back and forth at one another like a sequence from a Sergio Leone western: the mounting tension and uncertainty as gunmen size each other up, and the anticipation that comes before guns are drawn and bullets fired. But this sequence is neither western nor porn, so no pistols are drawn; instead, it exists in a space in-between, where the limits of genre itself are taken away, and the stock imagery of adult film can be turned into something else.

There’s a temptation to explicitly define adult films/sex films/porn—designations themselves that change fluidly with the context of what’s porn or what’s “legitimate” cinema; from the porno chic of the 70s that Jones refers to, to a contemporary moment of porn having exploded onto the internet—exclusively through the prism of hardcore (unsimulated) sex. This can often mean assuming that all films that include unsimulated sex—whether it’s the adult films of a director like Wakefield Poole or Fred Halsted; or lauded art cinema like In the Realm of the Senses (1976) and Stranger by the Lake (2013)—fall under the banner of “porn.” But Jones illustrates the multitudes that exist within these films. The absence of sex is layered, which reflects the migration of porn from movie theatres, to videos, to the internet, changing how it’s produced and consumed. There’s less of a need for these films to have narratives and ideas, and contemporary sites that host pornographic clips contain only sex acts themselves. From this vantage point, Jones’ work is undeniably radical, in how it refuses to classify desire through the lens of sex, instead creating a kind of anti-porno—using the imagery and tropes of adult films in an earnest way, but challenging what it is about the films that makes them erotic; pushing against the definition of “pornography” by showing how much exists beyond just the sex scenes, refusing the easy definition that’s so often forced on these films.

Jones shows porn and desire can be found anywhere one chooses to look. The audio in V.O. comes from art films—everything from Luis Bunuel’s Los Olvidados (1950), to the documentaries of Rosa von Praunheim, and Renoir’s La Chienne (1931)—but when placed in a certain kind of harmony with the image, it illustrates the construction and performance that creates desire. The layers of fantasy and projection in V.O. act as a distorted reflection of their X-rated roots. Sequences full of sailors and soldiers show how archetypal desire can be. Here’s a short, sharp, brutal exchange between two men – one in a position of power over the other:

“Lick my shoes.”

“I can’t.”

“I can’t, what?”

“I can’t sir.”

This follows a French VoiceOver wherein there’s confusion over language, a crossover between l’amour and la mort: love and death. By reframing scenes of sexual tension through the prism of life and death, Jones asks existential questions about porn as a genre; not only about what it’s presumed to be, what it might be, all of the possibilities that it contains when looked at through a new set of eyes. V.O. is more explicitly political than All Male Mashup, and feels like a companion to the earlier work The Fall of Communism. The film asks through its altered VoiceOver: “can homosexuality be a political position?” Through his work, Jones seems to answer: “yes.” When sex is removed from the equation, the gaze itself takes on a different meaning; it lingers, searches, defining bodies and what makes them desirable through a new criteria. The sequence in V.O. on the boat, which features the dialogue around l’amour and bootlicking, has a man undress while a VoiceOver talks about finding love. This forms an echo of the stark nudity – again, largely only hinted at – in The Fall of Communism. There’s always a desire for a thing in Jones’ films; after all, he’s manipulating films that provide these desires to their audiences. But to assume that the desire is simply to watch sex, or that all desire must culminate in sex, is an oversimplification that Jones’ films highlight; the absence of sex is by no means synonymous with the absence of desire.

These films are defined by their absences; there is something fundamentally unexpected or challenging about the idea of repurposing adult films and taking all the sex out of them. But Jones’ films reveal that the creation of absence doesn’t mean the birth of a void. Art, like nature, seems to abhor a vacuum, and as soon as one is created, its surroundings will fill that space. Desire is reconfigured through the absence of one thing, and Jones’ films transform their source material into tense vignettes of cruising and into Jean Genet-style meditations on love and power. By transforming the purpose of the material, Jones’ anti-porno films are fundamentally different to their original forms. Jones forces his audiences to ask what adult films are for: to desire on terms that, though devoid of sex, are far from sexless.