Organized by the Museu del Cinema, The Departments of History & History of Art at the University of Girona (UdG), and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the project “La construcción del imaginario bélico en las actualidades de la Primera Guerra Mundial.”

On 14-15 November 2013, the city of Girona hosted their 9th seminar on the origins and history of cinema. The Catalan gem might seem like an unexpected spot to hold a seminar on early cinema, but the city is a strong cultural component of its region and aside from its beautiful river location, stunning medieval old town, and thick hot chocolate, it boasts another pearl, its Museu del Cinema. Expertly run by director Jordi Pons i Busquet, the museum proudly showcases a very impressive array of pre- and early cinema artifacts, from hand painted glass slides to magic lanterns, praxinoscopes, zoetropes, and plenty other scopes and tropes, acquainting its visitor with the magic that became, was, and is cinema.

The seminar itself started out as a small and exclusively Spanish/Catalan affair in 1999, but its published proceedings of the previous 8 editions have thus far nevertheless amassed the largest volume of research output in the field of silent film studies in Spain. With the help of organizations such as Domitor, the seminar has meanwhile internationalized, going from hosting a few international speakers over the previous editions to dividing its presentations equally between international and Spanish/Catalan speakers this year. Among others, key speakers of the last few years were scholars such as Tom Gunning, Aldo Bernardini, André Gaudreault, Frank Kessler, Mary Ann Doane, Stephen Bottomore, and Charles Musser. Thanks to excellent organizational skills and impressive simultaneous translation in English, Spanish and Catalan, this year’s seminar brought together 24 presentations from a total of 8 different countries over the course of two days, focusing on a wide range of realist modes of discourse in early cinema.

J.E. Monterde of the University of Barcelona kicked off the conference with a keynote presentation that focused on distinguishing the concept of “reality” from that of “realism,” key notions that Monterde identified as “phenomenological” and “discursive,” respectively, and for which he turned to André Bazin and Christian Metz. Monterde’s keynote address preceded the panel on news actualities and served to open the discussion on cinema as a mechanical mediation of reality. The identification and definition of a “realist” mode of production on the basis of a phenomenological reality does, of course, quickly lead us to a generic context in which reality and realism seem, or seek, to be equal: the documentary.

Although there was not always a clean divide between documentary and fictional modes in the strict sense, conference papers were almost equally devoted to either, with the documentary mode taking a slight upper hand. The aforementioned ranged from papers such as Sila Berruti’s (University of Rome “Tor Vergata”) investigation of the scientific use of the cinematograph in Italian military experiments between 1897 and 1913 – leading Berruti to both a subdivision of the “war film” genre into three types, i.e. war/entertainment, educational/training and scientific/experimental, as well as an inquiry into the concept of the “real” as defined by military filmmakers – to Magda Rubí Sastre’s (University of the Balearic Islands) analysis of the onset of “tourist” cinema, also known as the travelogue, in Mallorca, looking especially at the Gaumont company’s efforts between 1910-1912 and revealing some interesting pictorial motifs that made the most of Mallorca’s geographical splendor; a case in point here were shots that used arched rock formations as apertures for framings in which the cameraman played with contre-jour and clair-obscur, creating silhouette compositions whilst not losing sight of emphasizing the documentary goal of the film. Rather, this approach combined an aesthetic approach with “natural registration,” creating a filmic experience that was interesting for audiences on a number of levels.

A pictorial approach to a documentary subject was not exactly surprising in the 1910s, however, for pictorialism was one of the main visual modes of the dramatic European (feature) film – a subject I discussed in my own paper on bourgeois realist pictorial strategies in European films between 1908 and 1914. In the wake of the European art film wave of 1908, a second swell of artistically minded films targeting the middle classes was being released from around 1910, employing a pictorial style visually, while often being motivated and sold via a popular “realist” discourse rhetorically. Louis Feuillade’s 1911 Gaumont announcement for the “Scènes de la vie telle qu’elle est” series in Ciné-Journal, France’s leading film journal at the time, for instance, drew on the popularity of naturalism embodied by French greats such as Antoine and Zola. Feuillade was one of the first to openly propagate and promote a film, or series, for its realism, trying to bank, of course, on its popularity in both literature and theatre, and distinguishing it from more sensational genres, to make it more esteemed. In reality, however, Feuillade’s films in this series were not so different from the other bourgeois art films being released by Gaumont. As Guido Kirsten (University of Zurich) discussed in his paper on what he termed the “programmatic” and “proto-reflexive” realism of Feuillade’s La Tare (1911) and Erreur Tragique (1913), Feuillade’s social criticism was dubious, for in spite of the filmmaker’s critical pretensions, a film such as La Tare, for instance, was inherently paternalistic and upheld the bourgeois society’s status quo. Like many of the times’ new art films, it was a thinly veiled melodrama, brought to the screen via more subtle acting (though certainly not always), deeper staging, and pictorial lighting.

Domitor president Scott Curtis’ (Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois) keynote on objectivity in early scientific and medical film viewing tackled a more stringent mode of realist discourse, wonderfully offset by Artemis Willis’ (University of Chicago) subsequent exploration of “performing the night sky,” on the interplay between astronomy and performance, cinema and pre-cinema, and objectivity and subjectivity. Curtis focused on motion picture technology as an ideal tool for mediating objectivity in a scientific context, a “hands-off” approach, if you will, that implied objectivity because it seemed to rule out patient-doctor subjectivity as well as mutual distrust between colleagues. The new medium was born out of the late 19th century scientific community’s demand for “aperspectival objectivity,” which, as its name suggests, was an approach that tried to eliminate mutual distrust and subjectivity by relying on verifiability and group validation, by implementing photography, projection, and cinematography, among others. The mechanical reproduction argument that was polemically used against photography and cinema in their quest to be recognized as an art form – since many critics perceived both media as mere mechanical recordings of reality – was the media’s main argument for use in a scientific context. There was, however, an awareness of the moving picture’s potential subjectivity, and thus the idea of restraint (i.e. no moving camera, long take, etc.) ruled the cinematographical recording of scientific activities.

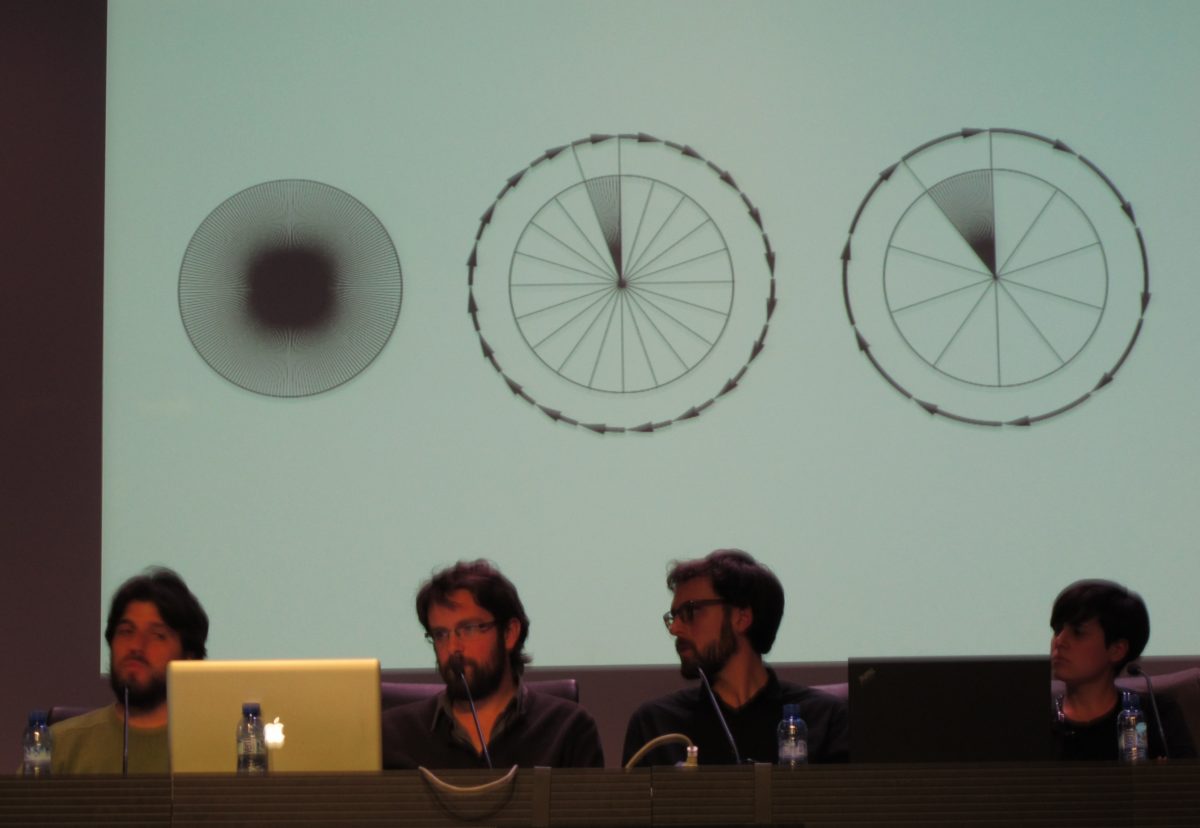

The dynamic exchange between science and aesthetics was continued in a few other lectures. Artemis Willis’ talk on 19th century astronomical lantern shows brought together “discourses of objectivity with experiences of the poetic and the unreal;” hand-cranked lantern shows were a multimedia art form that combined mechanics, projection, music and lectures with astronomical fact (as well as fiction). Willis discussed the problems that this form of edutainment faced with regard to the objective presentation of astronomical events, via both chronophotography and projection, and how this impacted, and transitioned into, the medium of cinema. In a similar vein, Pau Artigas Vidal, Marcel Pié Barba and Daniel Pitarch Fernández closed the conference with a lecture on their phenakistoscope project, a practical – and highly technical – implementation wherein aesthetics merge with mechanics in a fascinating effort to reconfigure and expand the possibilities of a versatile optical toy; check out some of the colorful results here.

Those interested in the topic of the conference will be delighted to know that a publication will follow later this year, which will be made available alongside previous publications on the Museu del Cinema’s webshop.